The impious maintain that nonsense is normal in the Library and that the reasonable (and even humble and pure coherence) is an almost miraculous exception.

Jorge Louis Borges, The Library of Babel

From the rows of polished aluminum desks in Rem Koolhaas’ Central Library—beneath the high, diamond windows that keep rain and the passage of time at a safe distance—artist Marc Dombrosky picks up scraps of abandoned notepaper.

“It’s a strange project,” he admits.

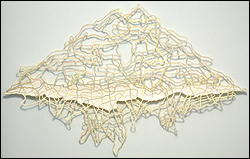

Scavenging society’s literary detritus, the Seattle-based artist transforms lost notes into something rich and odd. In the library, on the sidewalk, in coffee shops, all over town, he gathers up discarded handwritten notes and then embellishes the text by replacing the scribbles of pen or pencil with hand-stitched embroidery. The effect is unsettling. Because he’s done such fine sewing work, it’s hard to tell at first glance these aren’t just framed scraps of paper.

All these hastily scrawled bits—notes of book titles, shopping lists, even one man’s prison-release form—are transformed from ephemera to permanence in Dombrosky’s art. It’s a disturbing trajectory: What is thoughtlessly written and cast aside is suddenly woven into a text for all to see.

Dombrosky is one of a group of visual artists who troll the library and the written word for the meat of their work. Call them connoisseurs of minutiae. Or packrats, maybe. Four such artists from around the country came to the downtown library on Oct. 21 for a public discussion called “Mining the Library.” It was a fascinating evening moderated by Michael Klein, curator of Microsoft’s art collection.

Turning text into art is not a recent development, of course. The cubists pasted newspaper clippings into their paintings; conceptual artists Joseph Kosuth and Ed Ruscha have turned dictionary entries and banal slogans into ideograms drained of their original meaning and reduced to mere surface. Today, some artists are literally tearing apart the book in order to create art.

Among the panelists on this evening was Elaine Reichek, a New York artist who’s doing amazing things with embroidery. (“Oh yeah, sewing is hot right now,” Dombrosky tells me with more than a touch of irony.) Reichek’s modern-day samplers take a venerable women’s art—embroidered reproductions of artworks and inspirational homilies—and transform it into a study of language and obscurity. In Reichek’s recent body of work, titled “After Babel,” she’s reproduced the paintings of Samuel Morse (who knew—not just inventor of the telegraph, but an academic artist to boot). In another work, she’s stitched a copy of the Enochian alphabet, a 17th-century writing system invented by an English scholar who claimed it was transmitted to him by angels. Reichek’s whole project invokes a Borgesian wonder—an amazement at the fictions and facts that can be spun out of language.

Brainy conceptual artist Buzz Spector talked about his recent work with books. In one installation, Spector unpacked his entire personal library and sorted it by size on one continuous shelf circling the gallery. He’s photographed himself naked walled within his collection of fiction. And in one astonishing piece, Spector meticulously tears away pages of an antique book in successively wider strips to create a kind of diagonal MRI of the text. He told the audience he felt no guilt or secret thrill at defacing the book since it was a turgid 19th-century account of subjugating women.

Abelardo Morrell, a professor of photography from Boston, talked about his black-and-white photos of books gleaned from the Boston Athenaeum, one of the country’s most magnificent libraries. “I’m interested in the architecture of books,” Morrell said—and the photos do treat books with a kind of monumental grandeur. Tiny books are juxtaposed with table-sized books; water-damaged books take on the look of geologic formations; and the vast expanse of a library’s stacks becomes a kind of cityscape, a place of near infinitude. This is the library—as Borges observed—serving as a vision of paradise.

The most fascinating project, though, was David Bunn’s work with the abandoned card catalog of the Los Angeles Public Library. Bunn convinced the library to give him the entire discarded catalog, some 7 million cards in all. Bunn installed the whole thing in his studio and then took what he calls “core samples” of it. The results were twofold: a series of high- resolution scans of various stains from the cards reproduced as large abstract forms—plus sampled lists of book titles. The lists read like poetry, and the whole work dwells on the utopian ideal of the card catalog as a failed attempt to build an inclusive body of knowledge. Bunn’s lists point out the paucity of our experience: how, for instance, most of the book titles beginning with the word “girl” refer to meeting or impressing boys. Or, how there are only two titles in the 7 million that begin with “I feel”: I Feel Better Now and I Feel the Same Way.

In a similar fashion, Dombrosky’s found notes begin to accumulate meanings and stories they might never have had. “One that made me cry was this small piece of folded, rain-stained paper,” he said. It was covered in flowers and inside it read: Dad, Good Luck, Monique.

“I thought, what kind of bastard drops that?” Dombrosky pauses a beat. “Of course, I was probably invigorating the story.” The note’s original story, forever lost, becomes unimportant—what’s crucial is how it morphs in the hands of the artist into a study of loss and grief.

Of course, there’s more than discarded scrap paper to be found at the big new library. “If you come in with your senses open, there’s no end of material,” says Jodee Fenton, fine and performing arts coordinator at the Seattle Public Library. Not limited to books, the arts section is home to heaps of treasure: thousands of old vocal and piano scores; an archive of Victorian-era greeting cards; a picture file holding some 100,000 folders of magazine clippings spanning decades and ranging from Mongolian costume to early monorail designs.

For some artists, the library is becoming the free alternative to the museum—a place where one can dig for materials without the cost or the restrictions of the traditional gallery setting. And the Koolhaas space itself just feels like a place welcoming to artists.

“The first time I walked around in the new library,” says Dombrosky, “looking for the Gary Hill piece and looking at the space, I kind of forgot there were books there.”