Germany invaded the Netherlands in 1940, and two years later the Nazis took control of Lager Westerbork, a camp set up by the Dutch government to house refugees from Hitler’s regime. Westerbork was converted to a transit camp to hold Jews, many of them en route to death camps in Germany and Poland. The camp’s commandant, Albert Gemmeker, was an admirer of the arts and, more important, a fan of Jewish popular culture, and he went so far as to requisition funds to help the camp’s residents, a number of them cabaret and cinema stars who had fled Germany to perform in Holland, stage a weekly cabaret revue. Here’s the kicker: Anyone taking part in the revue was allowed to stay in Westerbork, thereby avoiding the weekly transport trains to Auschwitz.

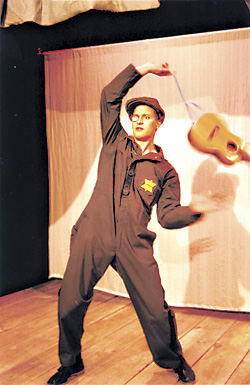

This is the historical background of The Westerbork Serenade, a one-man play written and performed by David Natale and directed by Gin Hammond for Odd Duck Studio. Natale, who first began working with this rich, tragic material in 1996 for his master’s thesis at the Old Globe Theatre, transforms the story of Westerbork into a universal meditation on art, sacrifice, and survival, without losing sight of the documentary details of this 20th-century atrocity. His play is at once sweeping and wrenchingly intimate, capturing the living texture of normal lives caught up in the hellish machinery of history. On a stark set defined by bare, flat-black walls, a glaring klieg light and three pallets pushed together to make the cabaret stage, Natale enacts Westerbork as a dark journey, following the trajectory of a handful of vivid characters from their arrival at the camp to their departure or death. Scenes of daily life in the camp are punctuated regularly by cabaret acts, such as Natale performing his adaptation of the 1944 Johnny and Jones song “Die Westerbork Serenade.” These numbers—sardonic, often hilarious commentaries on the camp itself—give the play a strong thematic resonance, and the underlying immediacy of the gallows humor is emotionally crushing. As one of the actors says to Max, the director of the camp’s revue: “This is the performance of our lives.”

Natale moves smoothly and convincingly among a number of memorable characters, each of whom embodies a particular aspect of the human instinct for survival. Among his most interesting creations is a mother with a babe in arms, a portrait of suffering filled with an utterly unsentimental fury that speaks truth to the sometimes deluded thinking of the rest of the inmates; at several points, the mother, looking down at her infant, says bitterly that the child “is just an ordinary Jew” compared to the cabaret stars avoiding deportation. Natale’s Max personifies the nagging guilt of a man who must make life-and-death choices among his own people. But perhaps the most fascinating character is Gemmeker, the Nazi commandant who believes that both Germans and Jews represent superior races. Hearing this complicated man say, “I believe children are the future,” is a chilling reminder that the evil Third Reich comprised ordinary people, with their banal hopes, self-contradictions, and self-delusions.

In researching and performing this play, Natale has made contact with Westerbork survivors, and his deep personal investment in the material, along with his obvious talent, gives Westerbork an undeniable emotional and moral force. The play is funny, sad, infuriating, shocking, and inspiring all at once. It moves with the relentless lockstep of tragedy, its terrors relieved only by the momentary flair here and there of the not-indomitable human spirit. Natale has expressed a desire to develop Westerbork into a fully cast stage play with an orchestra. It’s no slight on this excellent one-act version to say he should.