Know your vons! The Frye featured Albert von Keller in 2010, Gabriel von Max the following year, and now completes the von-fecta with Franz von Stuck, whose famous Sin—the lady wearing the lusty snake—is so central to the museum’s collection.

Stuck has his own museum in Munich, which the Frye’s Jo-Anne Birnie Danzker previously headed. She’s an expert on the German artist (1863–1928), which here in the U.S. is like being an expert on Australian-rules football. Stuck, like the other two vons, never really caught on in America, though Charles and Emma Frye encountered his work at the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago. World War I and its accompanying anti-Hun hysteria soon made all things German suspect, if not unpatriotic. (This may also have knocked down the price of Sin in 1925.) None of the three vons is well represented in the U.S., and the Frye is unusual among American museums in owning a healthy selection from the trio and having a director so knowledgeable about them.

What’s the Munich Secession? Basically just a spat among young artists and older gallerists in several European cities during the 1890s. Danzker organized a Frye show on that topic in 2009, when she defined the Secession as a “break-away from the conventions of 19th-century salon painting and salon-style exhibitions. For the first time, art works were presented on light colored walls, with space between them, so that viewers could concentrate on a single art work rather than be distracted by a multitude of other paintings hanging above and below.” Put differently, while not an end to group shows, the artist was allowed to shine beyond his school. The notion of the heroic individual vision, echoing Wagner and Nietzsche, coincided with the whole fulsome barrel of German Romanticism about to burst upon the sharp edge of the 20th century. On the other side, Stuck and his peers were tentatively tipping into notions of Darwin, Freud, science, and a world without God.

Today, says Danzker, she feels differently about Stuck than when she was running the Villa Stuck from 1992–2007. “He had eluded me,” she said at the October press launch. “I swore I’d never organize a Franz von Stuck exhibition again.” And yet here she was, doing just that, after editing a fresh new catalog for the show, which includes more than 100 works and supporting materials from the artist and his atelier. (Stuck was also a furniture designer and, with his wife, an avid photographer.) Danzker now labels Stuck a Symbolist, a term usually with French artists of his day—a somewhat more forward-looking crowd.

To my eye, at least, Stuck never leaves the past behind. His subjects are generally Biblical and mythological (some specifically German, like the alarmingly phantasmagoric sky hunters in Wild Chase). Most of his canvases are gloomy and dark, their light refracted as through an inky prism. They’re more sepulchral than sunny. Christ on his back in the 1891 Pieta, with Mary weeping over his body (which Stuck modeled on himself), is more morgue study than inspirational scene. The glowing eyes of Lucifer—raised above the picture surface—give the painting a vortex-like power, suggesting the hypnotic color whorls of Turner or Munch.

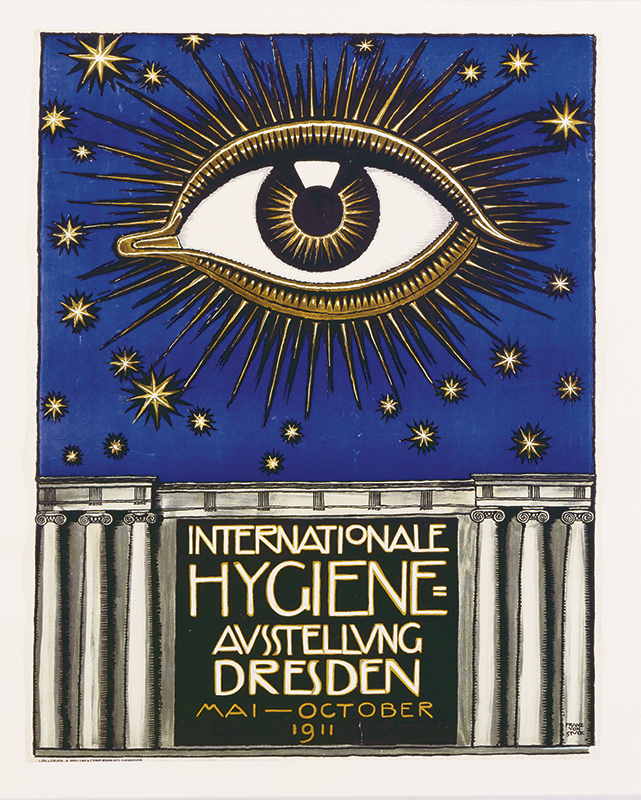

Stuck’s crisp posters and pamphlets for the Munich Secession, made before his fame as a painter, show the firm hand of a young draftsman who prefers the Hellenic to the Gothic. Orpheus plucking a red lyre, surrounded by adoring animals, has a pagan strangeness. All the fighting Greek gods and battling fauns are consonant with the German notion of kampf. Whether it’s Wagner or Nietzsche or you-know-who to follow, there’s a romantic/ historical reverence for battle and bloodsport. That was simply the zeitgeist of Stuck’s Germany, and he can’t be indicted for it now.

Born a miller’s son, Stuck only received the aristocratic “von” late in life; he jumped class about the same time that the old class distinctions were fading. He’s one of those transitional, fin de siecle artists who carried his key themes and references into the new age of airplanes, telephones, and silent movies. Yet he never seemed to enter that modern world. Photos, sadly not in color, show the elaborate architecture and furnishings of Stuck’s home (later to become the Villa Stuck museum), impeccably dressed in the raiments of the past. There are traces of Art Nouveau, but that’s about as far forward as Stuck’s aesthetic progressed. His students, notably Klee and Kandinsky, would become citizens of the new century, with Stuck a specter of the past, like his riders in the sky.

bmiller@seattleweekly.com

FRYE ART MUSEUM 704 Terry Ave., 622-9250, fryemuseum.org. Free. 11 a.m.–5 p.m. Tues.–Wed. & Fri.–Sun.; 11 a.m.–7 p.m. Thurs. Ends Feb. 2.