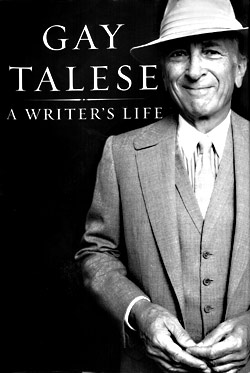

Gay Talese is one of the greats, a New Journalist who never gets old. At 74, he’s still as omnivorously curious as a puppy intent on sniffing out the entire universe, as proved in his new book, A Writer’s Life (Knopf, $26). His prose style is stodgier than his New Journo colleagues Tom Wolfe and Hunter S. Thompson. The true star of their stories is the colorful lens of the author’s personality, but Talese is an old-time shoe-leather reporter who builds his immense books out of innumerable bits of other people’s reality, patiently piling up and sifting clippings and his own notebook gleanings until, after many years, he emerges from his study with a new opus.

What originally made his journalism New was his distaste for the daily deadline and the obvious news hook: In his most famous essay, 1966’s “Frank Sinatra Has a Cold,” chosen by Esquire editors as its greatest ever, he made a virtue out of not getting an interview with his untouchable subject, concentrating instead on the Chairman’s entourage of nobodies, yielding a story, a perspective no one had seen before. Talese’s first book was titled New York: A Serendipiter’s Journey (1961), and he remains the most serendipity-dependent of writers, going his own way, confident despite not knowing at any moment precisely where he is going.

Publishers put up with his dilatory ways because the books are often best sellers of the most distinctive sort: the analytical 1969 tell-all The Kingdom and the Power, about his former employer The New York Times;the 1971 Bonanno Mafia family romance Honor Thy Father; the silly but extraordinarily lucrative 1981 work of sexual investigatory journalism Thy Neighbor’s Wife; and his own Italian immigrant family saga Unto the Sons.

Alas, Talese hit a dry patch after that 1992 multigenerational memoir. A short following stint with Tina Brown at The New Yorker produced little besides a 10,000-word piece on Lorena Bobbitt and her impromptu penisectomy on her husband. The article fell to Tina’s editorial knife, swifter and bloodier than Lorena’s excellent 12-inch kitchen cutlery. He had boxes full of bits not yet assembled into a book on the literati at Elaine’s, the celebrated Manhattan restaurant; other stalled projects involved an old place he calls “the Willy Loman building,” where 11 restaurants in a row went belly-up, and his colorful acquaintances on the New York cuisine scene, whose adventures he’d hoped to stitch together into his own version of George Orwell’s first book, Down and Out in Paris and London.

Instead, he produced this outrageously desultory semi-memoir, sort of a chronicle of his own career with a few pointers for up-and-comers who want a job like his. Call it Up and In in Manhattan and the Hamptons. Orwell was young, hungry, and focused; Talese is old and aimless. “I had nothing that I could rightly point to as a book in progress,” he confesses of Life‘s long gestation. “I was motivated by the notion I might rise above my state of indecision and discontent by writing about other people’s discontent and despair” in a book possibly to be called Profiles in Discouragement or The Loser’s Guide to Living.

As Life erratically unfolds, Talese keeps bewailing his wandering: “What did I intend to do with all this material? What was my story?” Contemplating his loser-building book, tentatively titled We Shall Now Praise Unfamous Men, he wonders, “Has the waywardness of my own life made me compatible with the floundering forces that apparently guide this place?”

As floundering accounts go, this one’s fairly readable. Talese rattles off disconnected vignettes and vaguely connected ones about Sinatra, some fun annals of Bobbittry, the epochal civil rights battle in Selma, Ala., heroic loser boxer Floyd Patterson, the Bonanno clan, and even a Chinese soccer player who loses a championship match in front of the entire world. To these he adds glimpses of his own biography, from scrappy youth to happy marriage (to mogul Nan Talese, publisher of Faux Journalist James Frey) to bewildered maturity. Since he makes so little effort to unify the scraps-from-a-shoebox narrative, the reader is encouraged to make his own connections. I savor the little verbal echoes: When Jackie not-yet-Kennedy whispered disappointedly right after her defloration, “That’s it?” it reminds me of what the volunteer rescuers of Bobbitt’s penis said as they held it aloft in the ER: “Is this it?”

Both of these phrases sum up my reaction to Life. It’s a good notebook dump, but not a great notebook dump. But any decade now, Talese is going to come up with a real book, and I’m betting it’ll be a keeper.