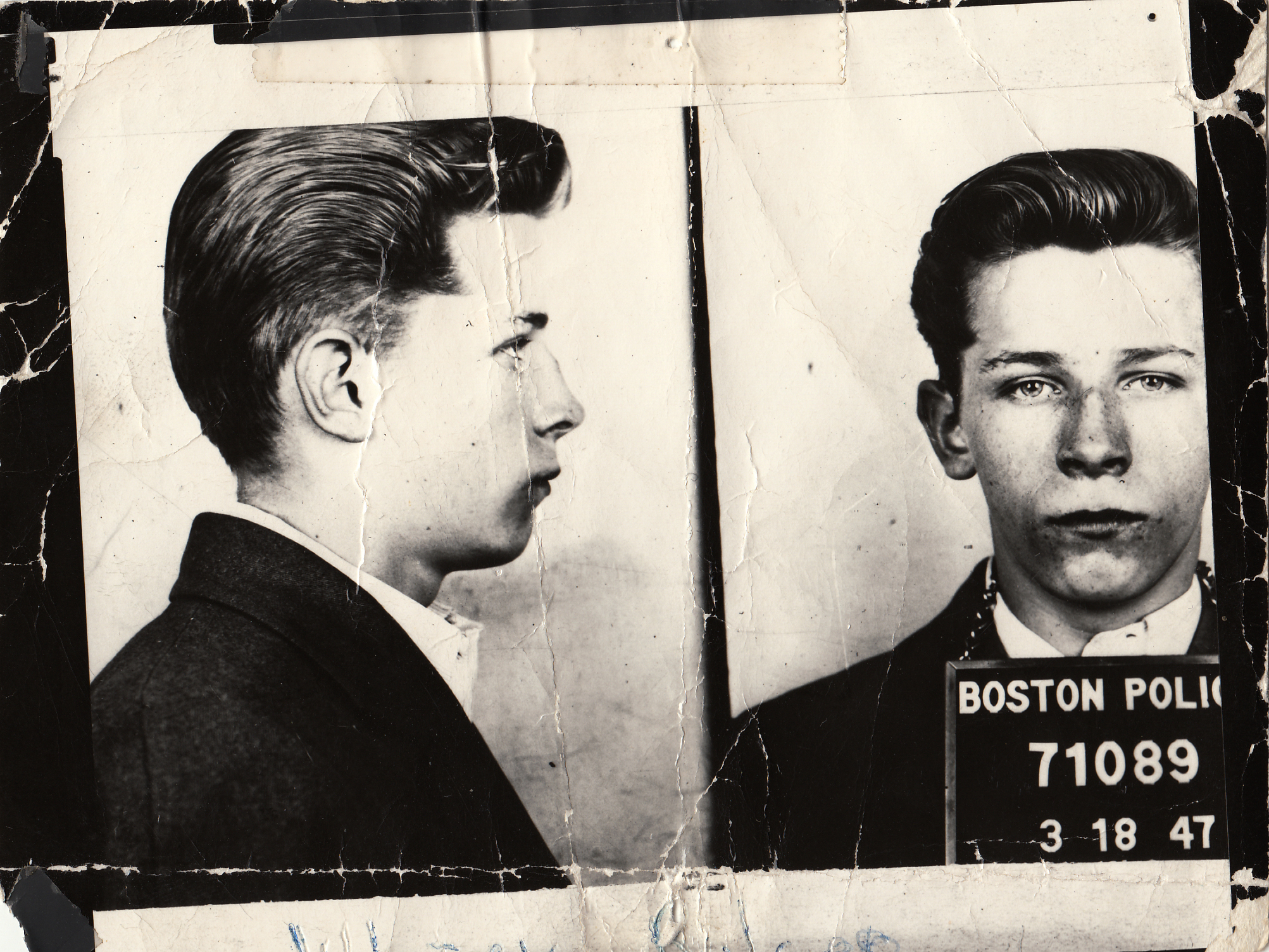

If you grew up in Boston, the criminal legend of James “Whitey” Bulger might carry some weight, particularly if you grew up Irish Catholic in the South End. A certain kind of outlaw is made an emblem of his ethnicity: Al Capone for the Italians, Meyer Lansky for the Jews, Frank Lucas for the blacks. Their taint becomes a synecdoche for unwelcome newcomers and minorities: See, all these damn, filthy immigrants are driving up the crime rate! Right-leaning newspapers, back in the day, loved to write about such tabloid crime figures; it was a way to displace nativist sentiment with law-and-order headlines. Then, like newspapers themselves, all those legendary gangsters got old and started dying. After a life in crime that began in the ’50s, Bulger went underground in 1995—tipped off by a corrupt FBI agent to avoid arrest—and was basically forgotten until his California discovery in 2011.

A lot changed during the interim, and that’s the challenge for documentary director Joe Berlinger, whose greatest successes have come in chronicling unknown stories (Brother’s Keeper, Paradise Lost, etc.). Bulger’s case is the opposite: His arrest and 2013 trial were widely reported (the verdict: guilty). Martin Scorsese’s 2006 The Departed, though an inferior remake of Infernal Affairs, turned Jack Nicholson into a very Bulgeresque ringleader, right down to the Southie accent. Now 84, Bulger reappeared just long enough to rekindle his infamy; then he disappeared again to spend the rest of his life in jail.

Why should we care about him now? Berlinger’s thesis, which he can’t quite prove, is that Bulger was never previously prosecuted because he was a protected informant for the FBI, owing to the notorious leadership of J. Edgar Hoover. And where the film is most interesting is its ethnic component: Hoover, in Berlinger’s telling, was so intent on the national Italian mob that he gave a pass to Bulger’s comparatively small-scale Irish-mob misdeeds in Boston. It’s a sensational charge; but, again, he can’t prove it. The sources are mostly dead; the public records aren’t there; and Whitey becomes one of those speculative, comprehensive, well-intentioned dead-ends that would’ve been better served by a fictional treatment—maybe even an opera.

Berlinger gets Bulger on the phone (via his lawyer), an exclusive. We meet the families of Bulger’s victims, still traumatized by decades-old crimes. And Berlinger gets the current federal prosecutors—but not the FBI—to talk frankly about their case; if there are any heroes here, it’s these guys. Whitey skips Bulger’s California years entirely, and we never get a clear personal sense of this sociopath who preyed on his own community for so long, then lived in quiet, happy retirement with his girlfriend.

Whitey is an admirable and thorough effort by an outsider to comprehend this blight upon clannish Southie, a betrayal by one of its sons. If the film falls short on final answers, it hints at a pervasive, fatalistic Catholicism that—along with some sector of the FBI—enabled Bulger for so long. “I guess there’s a reason for everything,” says Patricia Donahue, whose husband Bulger shot in the head in 1982. No, there’s not. But it’s reassuring to think that way, like lighting a candle in church.

Runs Fri., July 18–Thurs., July 24 at Sundance Cinemas. Rated R. 107 minutes.

bmiller@seattleweekly.com