WAKE UP, ALL YOU left-leaning ladies—our gender’s Lenny Bruce has arrived! As a columnist for the San Francisco Examiner and Salon.com, Cintra Wilson forged a ferociously funny reputation for colorful celebrity vivisections (she has gleefully skewered everyone from Henry Rollins and Barbra Streisand to Sandra Bullock and Jack Nicholson). What sets Wilson apart from other contemporary cultural critics is her awareness that while anyone can attack Holly Weird and its celebrated icons to humorous and satisfying effect, it’s far more risky, and revealing, to take on the very institutions of fame and celebrity.

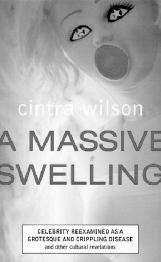

A Massive Swelling: Celebrity Re-Examined as a Grotesque, Crippling Disease and Other Cultural Revelations by Cintra Wilson (Viking, $23.95)

While Wilson’s prose and approach are consistently scathing, the real potency of her essays comes from her critical analysis of why the cult of personality so desperately needs deprogramming. “The slandering of iconage is a sport—not an act of aggression or bitterness, but an exercise,” she declares in her opening statement of intent. “It isn’t necessarily personal; it is generally not the icons themselves that I jolly and assail, it’s the huge tumescent aura of Otherness, the grandiose Largitude and supermagnified glamour of these deranged old musicians and dumb pretty kids and Sacred Cow Ornamental Personages that I attack.”

And yes, she is that wordy, but it’s rarely gratuitous. Her verbosity serves her quite well throughout this collection of essays, particularly when she anecdotally illustrates her arguments with examples culled from her self-imposed exile to Los Angeles—”In the last half-decade of the century, one must stick both barrels of the Armageddon fearlessly in one’s mouth and live the Fuselage of Human Error, which is surely Los Angeles.”

Wilson’s time in LA offered her the unsavory luxury of witnessing dozens of appropriately horrid incidents of fame-driven materialism and pseudospiritual gluttony. Stumbling across a box of New Kids on the Block fan mail gives her the opportunity to dissect the graduated scale of groupiedom (from “pink-faced teenybopper” to “this woman is out of her fucking mind”). Attending a yoga class where a hands-on instructor makes the mistake of correcting Lou Reed’s posture affords a red-faced example of the “inviolable bubble of invisible force around most stars that says ‘ . . . don’t touch me in any way.'” Wilson also shows how this untouchable status leads naturally to a public that embraces all those Richard Gere-gerbil rumors. Not only are Wilson’s examples funny, but they’re the perfect evidence for her claims against fame.

PARTICULARLY GRATIFYING is her willingness to make unpopular observations—evaluations so unsettling that one can envision reactionary criticisms that Wilson is crass and cruel, when she’s actually digesting the more moronic and self-congratulatory cultural leanings of Americans more fully. For example, in her Oscar study, she rails: “When it comes to sentimental porn, the Academy has made it perfectly clear that Retards are the order of the day. . . . Anybody portraying somebody with the boot print of a clumsy god pressed into his or her forehead—any dramatic role with waggling palsied wrist action or a dragging clubfoot and a tongue like a tennis ball—will take home a naked gold man on Oscar Night.”

Such declarations could no doubt get Wilson glared at across the dinner table of liberal posturings but are arguably much closer to exposing the biases and hypocrisy that so efficiently lubricate the Hollywood machine than any “thoughtful” NPR editorial ever could be. Her relentless, justifiably sarcastic gaze is unwavering, and although some theoretical redundancies in the closing chapter slightly dilute the punch of her arguments, her diagnosis of fame as a “perverse deformity, an ego swelling as ludicrous as an extra sex organ” remains refreshingly gutsy and scorchingly accurate.