I don’t worry about Google searches, but if the NSA profiles people by what they rent at Scarecrow Video, I’m on a few watch lists.

On a recent two-for-one Wednesday, I’ve got a Nazisploitation flick, a couple of ’60s Eurospy Bond knockoffs, and a spaghetti Western. Plus early-’70s Satanic-possession and women’s-prison movies on VHS that’ve never been on DVD.

“Stack o’ trash,” I say sheepishly at the counter. The clerk doesn’t judge me. She’s seen the particularly vile horror title in the stack. (Martyrs. You’re warned.) She recommends something similar for next time.

I began gorging each week when I recently considered leaving Seattle. I’d previously written for The Seattle Times that Scarecrow was the Alexandria library of video stores, and I wanted to take advantage while I could. (Disclosure: The store contributes surplus DVDs to my podcast.)

Recently I’d seen a couple of their jaw-dropping rare-clip compilations at the nearby Grand Illusion. A new espresso bar has a screening area with tables. Beer is even served during the free screenings—currently including Monday-night servings of the 1994 Showtime series Rebel Highway; the reggae documentary True Born African: The Story of Winston “Flames” Jarrett, who’ll attend the 6 p.m. Friday event; a crazy VHS compilation at 8 p.m. Saturday; and Sunday’s All About Eve (1 p.m.) and three TV episodes of Saved by the Bell (5 p.m.).

In addition to a powerful, searchable website, Scarecrow even has a podcast. It would appear that the iconic store—a perennial winner in our Best of SeattleR readers poll—is flourishing.

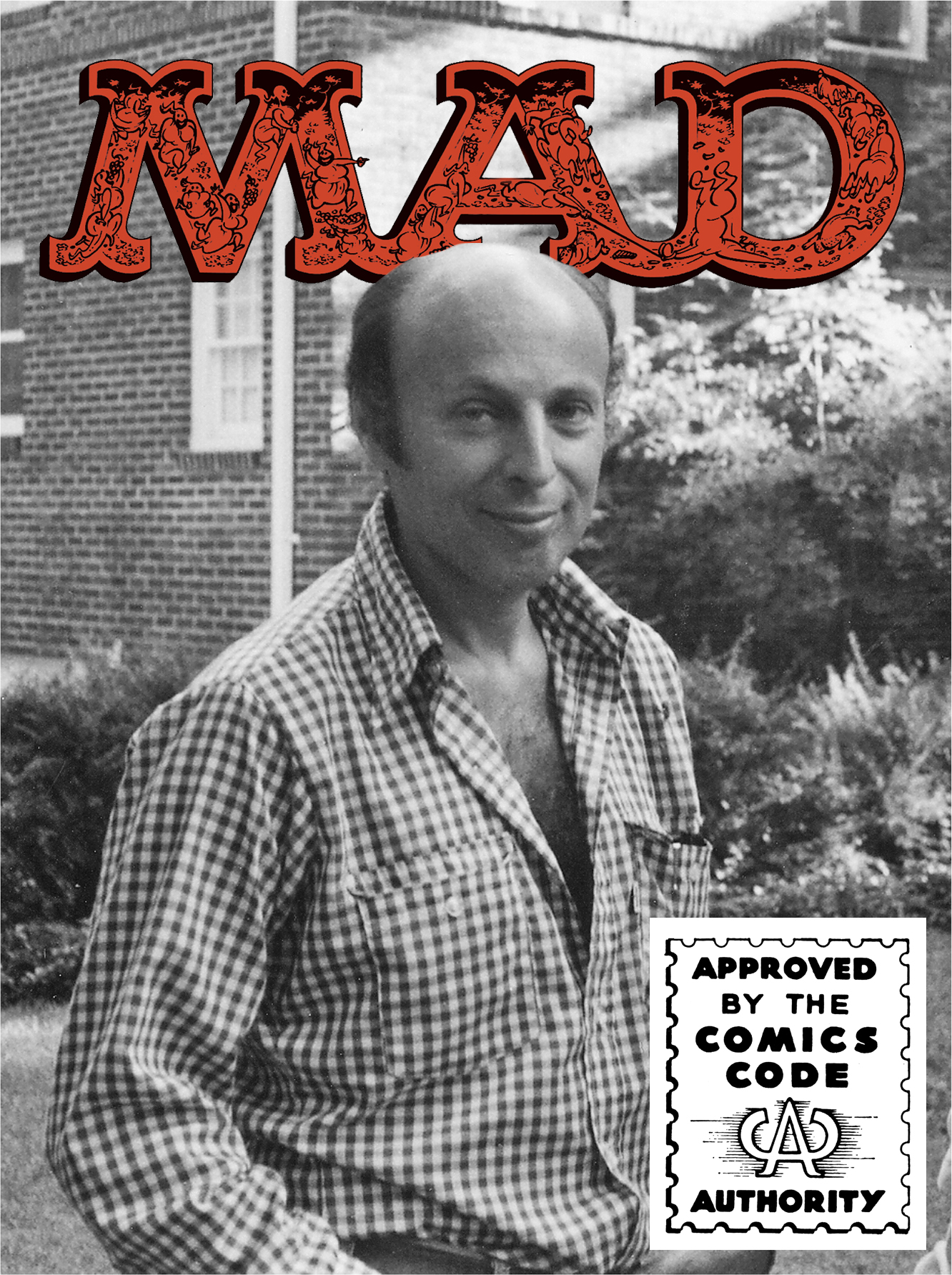

“What you’re seeing there is us trying new things to try to keep the store open,” owner Carl Tostevin tells me. “I would say we are struggling to the point that I just don’t know how long we are going to last.”

God damn it. Now the gorging is because a different clock’s ticking.

Two-for-one Wednesdays and seven-day rentals for older titles are also attempts to keep the store open, Tostevin says. They’ve cut store hours and compressed the inventory to increase space. Fixed costs—like health insurance for 30 employees—keep going up while business keeps going down. (You know the reasons: Hulu, Net-flix, streaming, VOD, etc.)

“The reason we have been operating as long as [the store] has is that I have a day job,” says Tostevin, who makes his living running the server-testing department for Microsoft Office. He’s never drawn a salary from Scarecrow. In 1998, he and Micro-colleague John Dauphiny bought—make that rescued—the then-struggling Scarecrow from George and Rebecca Latsios, who founded the store in 1988. (George died in 2003.) Tostevin’s the sole owner now—and his own landlord.

Here’s how it goes for him: “People say, ‘Oh, my God, you own Scarecrow Video. That’s so cool!’ And I say, ‘Hey, when were you last in?’ ‘Oh, I haven’t been in since I was in college.’ ”

Ouch. General manager Kevin Shannon reports that the number of rentals dropped 58 percent from 2007 to 2012, and sales have fallen by 35 percent. That fits with the industry-wide extinction of brick-and-mortar video stores, now in its tertiary stage. No one even knows how many are left, Home Media magazine editor-in-chief Stephanie Prange tells me. “The only people that took stock of that were distributors. There’s no one tallying it now.” She adds, “We just did a feature where each of us went around our neighborhoods and looked for video stores. Basically, all we could find were Redboxes and one Blockbuster.”

Blockbuster peaked at 9,000 locations globally in 2004, then went through bankruptcy six years later. Sold and reorganized, it’ll be down to 300 by the end of this month, according to Home Media—which once listed Scarecrow as one of the country’s iconic video joints. Meanwhile, roughly 36,000 Redbox movie-rental kiosks have metastasized nationwide, charging $1.20 per rental. Netflix is the other main store-killer: unlimited streaming for $8 a month and disc delivery with no late fees for another $8. (Scarecrow charges $4.50 per rental.)

“The video store as it used to exist is kind of gone,” Prange says. “The days where Quentin Tarantino used to work in a video store and you had these video clerks that curated titles—that just doesn’t exist anymore.”

Almost. And if I sound sheepish about my rental tastes, you should hear employees warn customers about the brutal late fees: the full rental cost for each late day. And those massive deposits for rare titles: $150, $30 . . . a $500 deposit on 1989’s Dark Planet on VHS made me handle it like a Faberge egg.

“It’s the only way we’ve found that we can keep track of our items,” Tostevin explains. “We’ve had late fees that are lower, and it’s hard to get people to return them, and they just walk.”

When Shannon started at Scarecrow 18 years ago, it stocked 23,000 titles. Now there are almost 119,000. A lot more has changed. For instance, he’s had a second job as a grocery checker since May. “In 1997,” he recalls, “we could make a decision to buy the #1 box-office comedy in the history of Poland on VHS for $90. We knew we could do that because we could rent a porno 300 times and we could pay for it.”

Yet today Scarecrow’s literature room out-rents the porn library—“anything from the ’70s and ’80s with a plot”—because of free online porn. Same for anime, once a hot commodity. Tostevin says people just pirate it online now.

At home watching 1973’s Three on a Meathook on VHS, I think how Scarecrow exemplifies the concept of You Get What You Pay For. The first time I stepped into the 8,200-square-foot edifice in the late ’90s, I felt like Dean Martin in a distillery. For decades, I’d searched for a low-rent English Bond knockoff called The Second Best Secret Agent in the Whole Wide World. Scarecrow had it. In the spy section. I’d begun to take note of an Italian hack/genius named Lucio Fulci who perpetrated The Beyond. Scarecrow had a Fulci shelf in its directors section. You don’t get that from Netflix or Redbox.

“Everybody has a story like that,” Tostevin says. “We were always about having titles that no one else had.”

As for the ticking clock, Tostevin says the coming holiday season is make-or-break. “I don’t foresee where we’re in such bad shape where we’d be closed by the end of the year. But we need at least an optimistic-looking end-of-year to build on the momentum into spring. There are knock-down, drag-out staff meetings. What is the right way to do this?”

Here’s how it goes for him: “People say, ‘Oh, my God, I can’t imagine Seattle without Scarecrow!’ But if you ever saw the scene in Titanic where they’re arguing about how the ship can’t sink, the engineer is going, ‘It’s made of iron and steel. I assure you it can.’ ”

news@seattleweekly.com

SCARECROW VIDEO 5030 Roosevelt Way N.E., 524-8554, scarecrow.com. 11 a.m–10 p.m. Sun.–Thurs., 11 a.m.–11 p.m. Fri.–Sat.