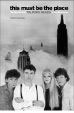

THIS MUST BE THE PLACE: THE ADVENTURES OF TALKING HEADS IN THE 20TH CENTURY

by David Bowman (Harper Entertainment, $25)

BAD ROCK BIOGRAPHIES are so commonplace that they’re hard to get angry about. Few people pick up the straight-to-paperback likes of (to name some recent examples) Martin James’ Moby: Replay or the Kill Your Idols series of pocket-sized cut-and-paste jobs on subjects like Beck, Tom Waits, and Elvis Costello expecting great, or even good, writing.

Instead, a book about a pop idol is a chance for fans to immerse themselves a little more completely in the band’s glow; all we ask for is a decent spread of facts, spiced with some little-known backstage intrigue and presented in the correct order of occurrence. Nobody reads the legendary Led Zeppelin bio Hammer of the Gods for author Steven Davis’ prose, insights, or critical acumen (this guy thinks the group’s best album is Presence, for fuck’s sake!); millions of people continue to buy it to read about the Shark Incident. (If you have to ask: On tour in Seattle, Zep’s roadies caught a red snapper and inserted it into a willing groupie.)

It’s a rare and beautiful thing, then, when a rock biography transcends its role as a mere reference tool, paints a vivid picture of its subject, and succeeds completely as a piece of writing (see Stanley Booth’s harrowing The True Adventures of the Rolling Stones, which chronicles the 1969 tour that ended in Altamont, for proof). This Must Be the Place, David Bowman’s new biography of the innovative New York band Talking Heads, on the other hand, is worth getting angry about because it does none of these things—and is unbearably precious about it. Bowman’s narrative arc is a battle between the band’s two largest egos: Bassist Tina Weymouth formed the group with her husband, drummer Chris Frantz, and singer/ guitarist David Byrne in the mid-’70s; they were soon joined by guitarist/keyboardist Jerry Harrison. Weymouth has been feuding with Byrne for years (his response has generally been to keep mum, infuriating her even further), and Bowman’s focus on her rancor is so unyielding, it becomes suffocating even before we even get to the band’s breakup.

Of course, it’s hard to know how seriously to take any book as riddled with errors as this one. Of My Life in the Bush of Ghosts, a 1981 album recorded by Byrne and Brian Eno, who produced three Heads albums, Bowman says: “More than one writer has credited Bush of Ghosts as the inspiration for industrial, house, even rap and hip-hop music.” Surely Bowman means that the album proved an inspiration to later musicians working in those styles, each of which, except house, was already fully recognized as a genre by the time Bush of Ghosts was released. Zapp’s vocoder-driven dance hit, “More Bounce to the Ounce,” is credited to James Brown, who’s never touched a vocoder in his life. The name of influential German rock band Can is gratuitously misspelled as “Cann.” Bowman also gets both the title and configuration wrong when he refers to a Kurtis Blow album called These Are the Breaks—the correct title is “The Breaks,” and it’s a 12-inch single.

SUCH SLOPPINESS is merely a symptom of the book’s overriding problem—namely, its arrogant tone. Bowman has interviewed musicians for Spin, Salon, and The New York Times Magazine, but he’s best known as a novelist (Let the Dog Drive, Bunny Modern), and he writes like he’s slumming. There’s a real black-shades-and-beret quality about his attitude toward the material—he seems to think he’s Norman Mailer writing about Marilyn Monroe, a “high” cultural figure blessing a plebian subject with his masterly touch. For instance, Bowman has an annoying stylistic habit. Of breaking up sentences. To give them more power. Only it doesn’t work. They look stupid. Smug. Especially the one-word fragments.

Not to mention the single-paragraph sentences.

Another annoyance is Bowman’s tendency to vague out on salient facts, which is supposed to be artistic but reads as cutesy instead. Discussing the band’s 1977 European tour, he refers to “a rumor . . . that David did something shocking involving a little American flag at the Portobello Hotel in London” that ended the tour—and leaves the reader hanging by never expounding upon what that something might be. According to a quickie 1986 Heads bio written by a pseudonymous author, Byrne allegedly shat on his hotel mattress and stuck a flag in it for the maid. Both a minor point and a minor legend—the Shark Incident it isn’t. But why bring it up at all if you’re not going to follow through?

That’s what made Talking Heads a great band: They lived up to their pretensions. What makes This Must Be the Place a terrible book is that it doesn’t.