Jay McInerney’s life wasn’t so good in the fall of 2001. Having fled the Manhattan high life he’d immortalized in his coked-up coming-of-age debut novel, Bright Lights, Big City, for down-home Tennessee with a wife and two kids, he had a midlife crisis, swan-dived back into New York party life, and dumped his wife for newer models. Despite an abortive stab at a novel about terrorists who blow up a Hollywood party to protest Western decadence, he was mired in what appeared to be terminal writer’s block.

Then he watched from his apartment window as the World Trade Center collapsed. Springing into action, he volunteered at a Ground Zero soup kitchen for almost two months, pulling strings at his old haunts to get fancy restaurants to donate great food. But it turned out what traumatized people really wanted was peanut-butter-and-jelly sandwiches. Biting into one, he had a Proustian flashback to the simpler joys of his childhood.

All of this gets replayed in coded form in his 9/11 novel, The Good Life (Knopf, $25), not a great book, but good in many ways and better than practically anything he’s written since his first book. He catches up with his version of Updike’s Rabbit and Janice Angstrom: Corrine and Russell “Crash” Calloway, the ambitious protagonists of his 1992 novel Brightness Falls, now settled into parenthood and competitive home cooking. Pretty much everybody’s marriage is a recipe for disaster. When a Calloway dinner guest courting bankruptcy brings Cristal, his bitter, sozzled spouse snipes, “Jim believes in cutting back on necessities, but he can’t imagine drinking Moët.” Russell can’t cut back on blow jobs from his secretary. Corrine’s in midlife crisis mode—endlessly rewriting an unsold screenplay adaptation of Graham Greene’s poignant adultery novel The Heart of the Matter. She’s ripe for some poignant adultery of her own.

Enter Luke McGavock, stumbling out of the 9/11 ashes and into Corrine’s arms. They both wind up working at a soup kitchen at Ground Zero and re-evaluating the heck out of their glamorama marriages and careers. He’s an unhappily married ex–Wall Streeter also in midlife mode, also blocked in his writing—on a book about samurai—and about to lose his shirt on his indie-cinema company.

The Good Life is actually more of a 9/12 novel than a 9/11 novel. McInerney wisely goes light on disaster description and writes what he knows: the folkways of glitterati and their longing for lost morals. For all his reputation as a guy who snorted cocaine off the hood of a Porsche in a Bret Easton Ellis novel (and real life), McInerney has always been conservative at his core. Luke and Corrine are rather innocent adulterers struggling to get back in touch with what might be called the Values of the Sandwich.

THE MORAL SCHEMA is way too schematic, but also intelligent, heartfelt, and acutely observed. Luke’s vile socialite wife tries to get him to score passes to Ground Zero for her curious rich friends. The police barrier at Canal Street becomes the new equivalent to the old velvet rope at the exclusive nightclub Area. Instead of just water- skeetering along the shiny surface of urban life, like Ellis, McInerney earnestly looks at the aspirations beneath.

But the dumber Ellis is a sharper stylist, and so was McInerney in Bright Lights and Brightness Falls. His prose sometimes plods here, and entire subplots expire pointlessly. Corrine has a screenplay pitch meeting with a womanizing moviemaker, but we never find out the upshot. She discusses the screenplay with Luke, but he illogically fails to inform her he has a film company, whose fate we never hear about. I’ll bet that, in the reportedly sprawling previous draft of the novel, trimmed by editor Gary Fisketjon, these threads led somewhere. As a result, McInerney introduces many good supporting characters who don’t support anything—they just wander in, score sociological points, and wander off. Dialogue natters neatly, a little like The Thin Man, but with no sense of direction. It’s not really driven by what each character wants, but by what the author wants to get said.

Still, he does manage to say a mouthful, and a mind-full, about the rueful progress of his generation, marching powderlessly and powerlessly into the mire of middle age. At age 51, he may be the best observer, if not writer, of boomer failings and yearnings. In fact, the book would be better if he aimed lower, attempting strictly to skewer our times instead of trying to write for the ages like his idol Fitzgerald. The Good Life isn’t what you’d call literary Cristal. But it’s as good as Moët gets.

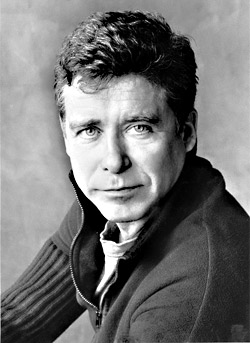

Jay McInerney will appear at University Book Store, 7 p.m. Mon., Feb. 27.