URMILA NAGAR AND CARMONA FLAMENCO

Museum of History and Industry, 2700 24th E., 522-4404. $15 8 p.m. Sat., July 7

FEET OF FLAMES

Key Arena, Seattle Center, 628-0888. $35-$85 7:30 p.m. Thurs., July 12

IT COMES, probably, from listening to the sound of our own feet on the pavement as we walk. From the simple repetition of bipedal locomotion, it isn’t that far to create patterns out of those sounds— grouping them into sequences until “1, 2, 3, 4” becomes something far more complicated. Almost every culture boasts some kind of percussive dance tradition, some way for us to hear the sound of feet on the floor, and this next week is full of different opportunities to listen to those compelling tattoos.

With its proud and passionate movements and songs full of yearning, flamenco might seem far removed from the northern Indian dance form kathak, which spins ancient, complex tales of gods and heroes. In truth, though, flamenco is a direct descendant of kathak, carried by immigrants from the Punjab along the North Coast of Africa and across the Straight of Gibraltar to southern Spain. The immigrants became the Gypsies, and their dance form became flamenco—changing its name but retaining its emphasis on rhythm and detailed gesture.

Looking beyond surface differences, there are remarkable similarities in posture and attitude between flamenco and kathak as well: The lower body maintains a powerful connection to the earth while using the feet with great dexterity, pounding out rhythmic phrases in complex sequences of heels, toes, and full-footed stamping. The upper body, meanwhile, curves and twines, exploding with clapping sequences that expand on the patterns of the footwork. Through all of this, the focus of the dancer’s face and eyes draws the audience further into the performer’s world. These dances were originally intended for intimate spaces—the campfire, the temple, the cafe—and not for the more formal distance of a theater space.

Within these close environments, though, there is great freedom for the performer. Both dance forms incorporate improvisation, allowing dancers to respond to the moment and their own sensibilities within the framework of the overall structure. In their upcoming show, kathak dancer Urmila Nagar and the members of Carmona Flamenco will use that freedom to revitalize the relationship between their two traditions. Both guitarist Marcos Carmona and tabla player Vishal Nagar will explore those rhythmic connections.

In flamenco, a 16-count phrase will often be divided into two sets of eight, or even four sets of four, while in kathak the 16 counts form a single unit, so that repetition occurs over a longer period of time. Working with these larger phrases, the kathak dancer will take longer to develop an idea or structure. Originally, performances in this tradition might last all night, and though contemporary concerts aren’t that lengthy, there is still the feeling that time is passing. Duration is also a part of a flamenco performance, as the tangible relationship between dancer and musician develops. While they are deeply connected by a shared rhythmic pattern, the intimacy of their communication as they shape their phrases transcends our awareness of the clock.

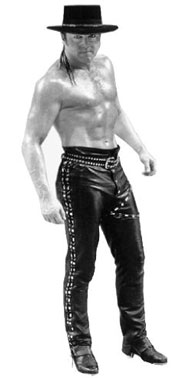

FROM THE TEMPLES of northern India to local sports arenas, rhythm connects us all, moving through the space and dancing through life. The thrill of that connection between soloists is altered when the stage is filled with bodies, all moving in synchrony, united by rhythm. Starting with Riverdance and its many offshoots, Michael Flatley and his colleagues in Feet of Flames have capitalized on our fascination with large groups moving in unison. These arena shows extend the dancing beyond our peripheral vision, filling our eyes with movement as a series of kaleidoscopic images. At the center of the circle is Flatley himself, as controversial a figure in dance as you might ever see. His popularity brings a much wider audience to his concerts than would ever buy tickets for a more conventional dance program, but his enthusiastic combination of varied dance traditions, implying connections that might not otherwise exist, worries some dance scholars. If you can watch the program without taking it as gospel, though, the sheer number of moving bodies creates an incredible sense of momentum, and our kinesthetic reaction is intense. Flatley has learned the same lesson as film choreographer Busby Berkeley: More is more. It’s hard, though, to take him as seriously as he takes himself, as his oiled-up pecs glisten beneath the spotlights. But his undeniable commitment to theatricality carries us past any qualms we may feel about the polyglot nature of the event.