MORE THAN A MEMOIR about a tortured adolescence, Keith Fleming’s The Boy With the Thorn in His Side is an ode to Edmund White. White, the author of the classic memoir A Boy’s Own Story and one of the leading men of gay letters, was also Keith’s uncle, with whom Keith lived at age 17 and whose kindness gave his nephew “the feeling that anything, magical things, had become possible.”

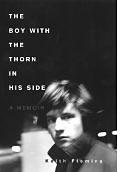

The Boy With the Thorn in His Side

by Keith Fleming (William Morrow, $24)

Keith wasn’t always so optimistic. After his parents’ divorce, he moved into his mother’s Chicago home and attended a junior high school with the philosophy that “children are innately wise about their educational needs.” The combination of a mercurial mother just realizing her lesbianism and a stray son recently set upon by hormones and acne triggered an explosion that catapulted Keith to his father’s house, ruled by an insecure stepmother. Rather than burden his new wife with a teenager used to laissez-faire authority, Keith’s father shuttled his son between psychiatric institutions where “patients were guilty of nothing more than cutting classes, telling Dad to ‘fuck you’ once too often, running away, or having their marijuana stashes discovered.” Once Keith’s mother realized her child was spending his adolescence behind bars, she made arrangements for him to live with Uncle Ed in Manhattan.

DESPITE HIS PARENTS’ early reservations about letting their son live with a gay uncle, Keith didn’t share these prejudices. He saw his uncle’s homosexuality as “exotic” and eventually learned much from the sexually voracious New Yorker who had not yet published his first novel. Uncle Ed introduced Keith to Proust and Nabokov, taught him “tidbits about English” such as the difference between eager and anxious, paid for his prep school, and provided him with aesthetic improvements such as medication for his acne, a Barneys wardrobe, and tips like “hemorrhoid ointment applied under the eyes . . . [is] the best way to get rid of bags.” Thus Keith eventually returned to Chicago a sophisticated urbanite, a blossoming intellectual, an adult, and, most importantly, someone who finally found confidence in himself. The chapter entitled “Life with Uncle Ed” doesn’t occupy more space than the others; Uncle Ed’s just one of the many memorable personalities illuminated here. But he’s the only person referred to with gushing statements such as, “Under my uncle’s distinctive influence I became a new and better person.”

What’s frustrating about this memoir is that Keith doesn’t make equally weighty comments on the other people in his life. As elegant and haunting as his prose might be, he possesses the voice of someone who’s spent years in therapy, only to be numbed into acceptance of family members’ wrongs. He does not question the fact that his mother excused herself from her son’s teenage years so that she could frolic with her newfound lover. He exhibits no rage against his father, who signed his son over to a notoriously sadistic doctor who threatened his young patients with rape. And he includes no rant against a society that propagates the lie that a nuclear family is preferable to a family based on love, even though he experienced exactly the opposite. Without the passion and the soul-plundering, we’re left wanting more of Keith Fleming’s spirit, and less of Edmund White’s.

Edmund White reads from his new novel The Married Man: A Love Story at Bailey/ Coy Books June 8 at 7pm.