Ever since God gave Adam the job of naming things, the rest of us have been busy finding ways around those labels. In the dance world, ballet and modern used to be mutually exclusive camps, with vastly different techniques, traditions, and aesthetic models. Jazz dancers were separate from flamenco artists; tappers didn’t mix with ballroom. But as dance became more popular through the last century, it also became less “pure”—combining different strains of the discipline in crossover works or branching out to absorb elements outside old-school dance traditions. As we move further along this pathway, the original labels seem to mean less and less.

Instead of digging into its historical categories, dance today is often just one component of a larger event—movement combined with theater, with visual art, with music or text. Just as the terminology is shifting in those other art forms, dance descriptors seem to be drawn on fundamental levels. The idea of “time-based arts” is a large umbrella that covers pretty much anything intended to change while we watch it.

Increasingly, the main differences among dance bills seem to be in the presenters rather than in the art they present. Most of the audience that fills the halls of On the Boards doesn’t really think about going to see Pacific Northwest Ballet, but last year both organizations staged new dances by Mark Morris. On the Boards gave us work by Crystal Pite last October; this November, it’s PNB’s turn. (See our Fall Arts calendar, page 24, for all performance dates.)

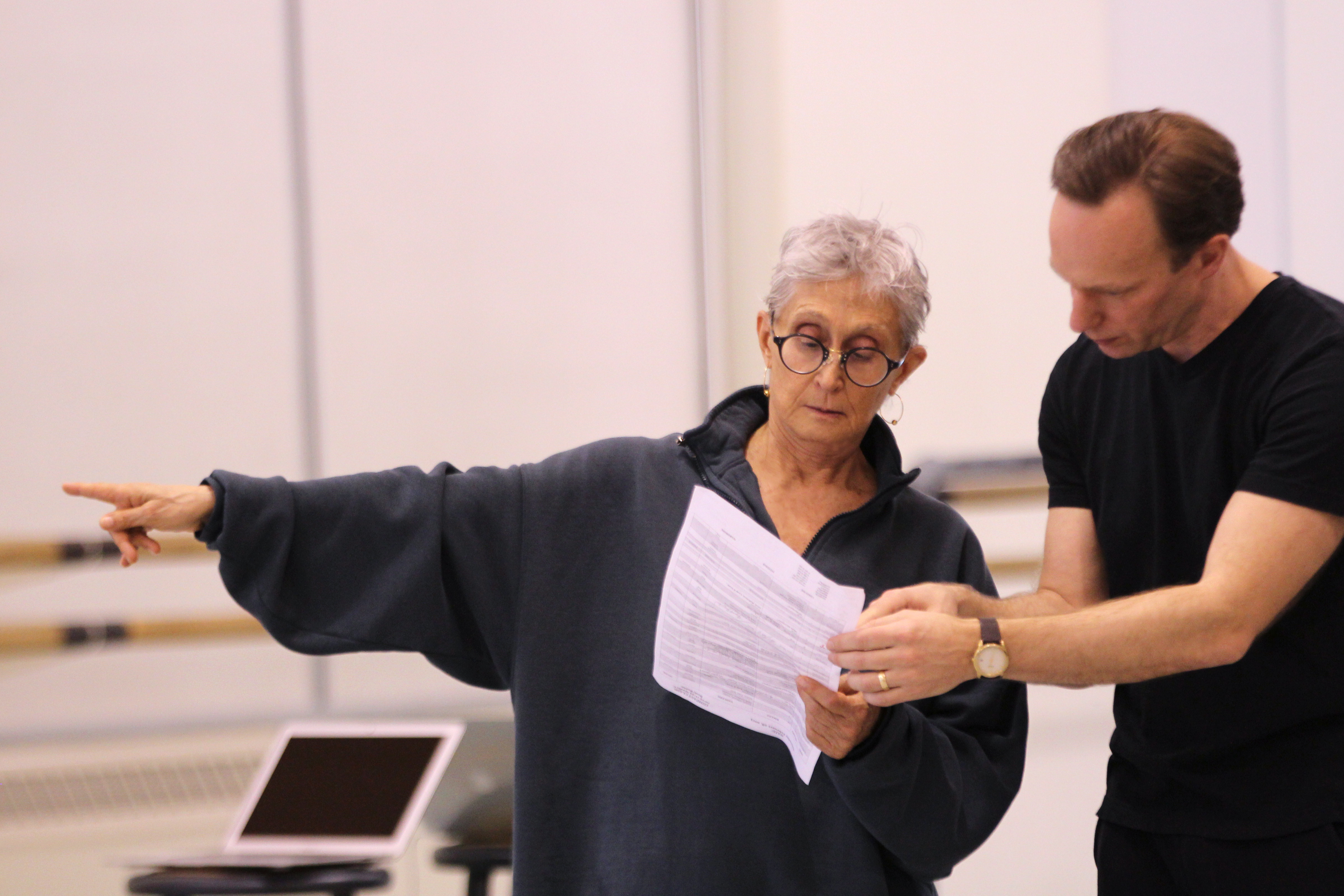

This fall dance season is full of works that mix influences and genres. PNB is adding to its collection of choreography by Twyla Tharp with a pair of dances. Brief Fling, which comes from her tenure as an artistic associate at American Ballet Theater, plays games with ballet technique and structures. Waiting at the Station is a new work, using music by R&B legend Allen Toussaint. Tharp is still the reigning mistress of crossover choreography, combining a broad palette of traditions. In many ways, her work is a model for contemporary dancemakers in the same way that George Balanchine was a pathfinder for neo-classical ballet.

Right after its Tharp program, PNB will present another collection of works that draw from multiple sources. Jiři Kylian holds much the same place in European dance circles that Tharp does in the U.S.: not the first person to experiment with combining genres, but probably the best known. In his work for the Nederlands Dans Theater, he’s created a body of choreography that companies everywhere long to perform. PNB already has two of his more lighthearted dances, Petit Mort and Sechs Tanze, in its repertory, and is adding the poignant Forgotten Land. We’ll see all three in November, along with a new-to-us work from Pite, Emergence.

Pite started her career as a ballet dancer, but when she moved to Frankfurt to work with William Forsythe, that professional label became much more elastic. Forsythe has pushed the boundaries of “ballet” into experimental-theater territories, embracing a wild combination of kinetic possibilities. Coming out of that environment, Pite makes work that needs the strength and articulation of ballet training, but also requires a dynamic commitment and flexibility that comes from modern, jazz, and martial-arts traditions.

Donald Byrd is another choreographer with a magpie aesthetic. His work for Spectrum Dance Theater is powered by the expressive tradition of modern dance. He’s long been engaged with political topics (especially in his early creations), but his movement vocabulary is laced with traditional balletic virtuosity. This autumn he’s presenting work from both sides of that divide, with a commentary on Balanchine’s Prodigal Son and a revival of his own The Minstrel Show, which is sure to be as controversial as it is bravura.

Among all this cross-sampling are a few examples of work that stays true to a singular vision. At the University of Washington, Hannah Wiley is using the Chamber Dance Company to keep historical works from the modern-dance tradition in a living repertory. Working with graduate students fresh out of the professional world and trained in a variety of styles, it can be a challenge to get them to narrow their performance focus on an older model. Yet CDC programs are often a living history lesson. This year’s concert—featuring early work by modern pioneer Doris Humphrey—should be a great example of that pure approach.

UW alumnae Paula Peters and Rhonda Cinotto bring a similar philosophy to their start-up company, the Contemporary Jazz Dance Project. Jazz dance has always been a loose category, with influences from vernacular music and social dance. Today, with hip-hop, competition, and cheer-team styles sometimes identified as jazz, the field has really exploded. Yet Peters and Cinotto want to bring a more traditional approach to their work.

At some point, we may invent some new dance categories and sort our heritage into a new set of file drawers. Until then, and certainly through this fall, it’s a fusion world in dance.

dance@seattleweekly.com