In calling Twelfth Night by its name in the original First Folio, Twelfe Night, or What You Will, director David Esbjornson presumably means to say this is the real thing, the play steam-cleaned to its essence. Twelfe is a funny show, but astringent—every laugh has what critic John Wain called “a sharp nipping air blowing in from the tragedies.” Shakespeare was about to create Hamlet et al., and his humor was taking a saturnine turn.

In the quietly spectacular opening, redheaded siblings Viola and Sebastian are shipwrecked in shimmery, bubbly midair, and separated. Viola must go it alone on Illyria’s strange shore. Scared yet scrappy, she invades Illyria in male disguise. But she’s woman enough to fall instantly for the local ruler, Orsino. He, however, already loves local countess Olivia, who, in turn, falls for the boy Viola pretends to be.

Esbjornson brackets the play with lighting wizard Scott Zielinski’s unnaturally bright primary colors, reminiscent of a Peter Brook production. In the first and last scenes especially, the effect is pretty yet eerie. It signals that this is no tourist’s Shakespeare, safe and complacent. Michael Pavelka’s set, too, makes Illyria a menacing place: forbidding sea cliffs in the background; in the foreground, a standing wave of wood that rises to a tower topped by a DNA-like spiral. The wood is shredded, redolent of decay; every soul on this isle is likewise a rotting monster of selfish self-delusion.

Sadly, the leads don’t quite measure up to the setting. A great Viola is like Krug champagne—deep and complex—but Christine Marie Brown’s simplistic Perrier Jouët fizz is just passable. She’s a sexless tomboy with a quizzical Ellen DeGeneres mien. Barzin Akhavan is disastrously bad as Orsino, bland as a plastic lox, and in poor voice. Cheyenne Casebier’s Olivia is too inert, though she’s got glints of screwball-comedy brio, and wears Frances Kenny’s marvelous balloony, ballroomy costumes with a model’s aplomb.

But redemption comes from the supporting players. The star performance is Charles Leggett’s superbly realistic Sir Toby Belch, Olivia’s drunken sponge of an uncle. Leggett’s Toby is the sole Illyrian cursed with self-knowledge, his eyes as precise as his calibrated stagger. He’s a clown in palpable pain—a tricky part to play.

Toby procures free drink by advising another clueless contender for Olivia’s aristocratic hand, Aguecheek—the splendidly spindly Andrew McGinn, who sports a suit so lurid Phil Spector might wear it to court. And Toby transmits his misery by helping manipulate Olivia’s servant, Malvolio (Frank X), into thinking he, too, has a chance with the countess.

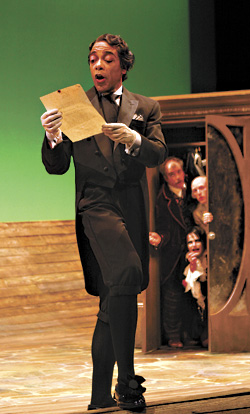

Malvolio is a weird, disturbing outsider. When John Gielgud directed Laurence Olivier, he asked him to play Malvolio as “very, very Jewish”; Olivier insisted on playing him as a camp gay hairdresser. Frank X’s Malvolio is more of a black intellectual with James Baldwin’s austere hauteur, only straight. His black skin lends horrific weight to the uneasily sadistic comic scene in which he’s chained and tortured in a dungeon by Toby. The play’s high jinks and romantic fantasy shiver in Malvolio’s dark shadow. Frank X stands tall enough in the part to cast that shadow.

The other bizarre outsider is Feste, the play’s morally ambiguous clown, commentator, and provocateur. David Pichette, clad in a checkered Harpo Marx coat complete with honking horn, plays the farce coolly, with a circumflex eyebrow and icy snake’s gaze. His head, slightly lightbulb-shaped, like a high-IQ human of the future, regards all in a way that does not quite conceal a private amusement. It’s a smart performance, sharply etched. But this is Shakespeare’s play most deeply infused with music, and Pichette can’t carry a tune in a bucket. When he sings with an ensemble, it’s lovely and sad; when he solos, it’s an off night at the karaoke bar.

Three actors do amazingly well in smaller parts. Mari Nelson snarls with style as Maria, Olivia’s servant and Malvolio’s nemesis. Brandon Whitehead milks some of the night’s biggest laughs from his palsied shuffle as the incredibly decrepit priest. I saw it with my own eyes, but I have no idea how Nick Garrison makes so much of his attendant’s role. Partly, it’s his ghastly goth makeup and bad tranny-Catholic-girl getup (another slam-dunk for Kenny). But it’s not just the clothes that make this man. Garrison’s got subversive presence. In a play with so many immortal words, it’s remarkable how many top-scoring bits have no words at all.

Esbjornson has a sure hand, though his pacing is too monotonously metronomic. The show could use a Jolt Cola—it’s rich in promising moments that bubble without coming to a full boil. Not that I recommend lawbreaking, but in a similar situation, film director Lenny Bruce once put Benzedrine in his cast’s coffee urn without telling them. Made a world of difference.