Some summers, the Seattle Chamber Music Society offers surprises: world premieres, percussion recitals, concert programs on which the most familiar composer is, say, Georges Enesco. This year, SCMS is playing it a little safer with repertory (its Big Four: Mozart, Beethoven, Brahms, Dvorak) to compensate for the risk of expansion—it’s added a six-concert August series at the Overlake School on the Eastside (through Aug. 12; 206-283-8808, www.scmf.org) to its usual July series at Lakeside School and its January Winter Festival at Benaroya Hall.

The society’s concert production is by now a well-oiled machine, with format and ambience tested over 24 seasons. Though experimentation and innovation may not be priorities, fortunately its audience isn’t stagnating, and the move to Overlake—plain and handsome white buildings set on grounds carved out of the tall forests of deepest Redmond—has brought new listeners. Executive Director Connie Cooper notes that in addition to the “hard-core audience who will attend our concerts no matter where they are held”—and no matter how gruesome the traffic, by the looks of the first concert—the Overlake location is attracting “many, many people who are brand-new to the organization. I just took a phone order from a Kirkland resident who has been aware of the festival for years but never attended. He went to Overlake last night [Aug. 3], loved it, and has now purchased tickets for Friday’s concert.” This echoes the success of the organization’s January series: “When we launched our Winter Festival seven years ago, we found that about 40 percent of the ticket buyers were new to us. That has held true, with a significantly different audience from our Summer Festival.”

From a musical standpoint, the salient fact of SCMS concerts are their spontaneity— musicians flying in from all over are shuffled and reshuffled into ad hoc ensembles. It’s interesting to speculate on ways in which limited rehearsal time might affect performance—sometimes for ill, but sometimes for the better. In some cases, the problems are audible: for example, the Mozart piano trio at the July 11 concert, sloppy in ways it shouldn’t have been, or the Mozart Clarinet Quintet at the Overlake inaugural, showing a slight lack of polish and some misjudged balances—compensated for, however, by clarinetist Frank Kowalsky’s warm, velvety tone.

Sometimes the issues are interpretive rather than technical. A longer rehearsal period surely would have facilitated deeper probing into Shostakovich’s 1940 Piano Quintet (July 11, with Carmit Zori, James Ehnes, Toby Appel, Robert deMaine, and Jeremy Denk).Conventionalized in expression, the work’s depths went unplumbed—the scherzo exhibited a good-natured vehemence but nothing darker, while the finale, blithely sunny, gave little hint of the wistfulness, nostalgia, or even outright irony that makes this quintet such an eloquent document of Shostakovich’s psyche and of his time and place.

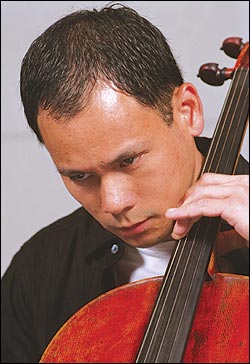

And yet sometimes the performances offer a freshness that more rehearsal wouldn’t necessarily improve upon. Amos Yang and Wonny Song played Shostakovich’s Cello Sonata strongly (Aug. 3); Yang was particularly impressive in the second movement, bringing a focused intensity to rambunctious passages that tempt many cellists to flail about. Ravel’s String Quartet (July 8) was a daring choice—the work’s shimmering, ultrasubtle iridescence seems to demand a precision only attainable by quartets that have played together for years. Ehnes, Jonathan Crow, Roberto Diaz, and deMaine opted instead for breadth and richness of tone, with attractive results. This was a well-upholstered Ravel. Then there are works that simply don’t reward intensive rehearsal, like Dvorak’s Piano Quartet in E-flat (Aug. 3), so pretentious and empty that trying to dig beneath the surface would be a waste of time—a piece nevertheless played with first-class sensitivity and energy by Ehnes, Phillip Ying, Bion Tsang, and Rieko Aizawa.