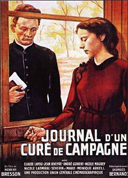

Tormented by suspicious parishioners and his own spiritual anguish, the young cleric (Claude Laydu) in Robert Bresson’s 1951 Diary of a Country Priest lives on stale bread soaked in wine, burning the candle of his devotion at both ends as he becomes unduly involved with the domestic drama unfolding at the local château. Bresson’s movie is almost as demanding in its purity as the priest. The film is experiential: The priest’s suffering is not to be explained but lived; and the action is explicated by his voiceover narration, punctuated by shots of his journal entries as they’re being written. Its every sound and image unobtrusively precise, Diary is a movie of emphatic understatement: contemplative yet abrupt, eloquent and blunt, oblique but lucid. The priest is a contradictory personality—self-effacing, willful, and honest to a fault in his attempt to save the château’s mistress (the movie’s only professional actress) from a despair he recognizes all too well in himself. Few artists since the Renaissance have so convincingly wed the aesthetic to the spiritual. Diary’s final shot makes its allegory absolutely apparent even as the priest’s last words—“All is grace”—suggest cinema itself is the holy sacrament. (NR) J. HOBERMAN

Nov. 18-20, 7 & 9:15 p.m., 2011