Ariel Dorfman’s new play about purgatory has one hell of a pedigree. He’s Old Left royalty—his Marxist dad named him Vladimiro, after Lenin, and though he dropped his first name for his middle, Ariel, Dorfman still gets red cred for his family’s having to flee New York for Chile after close friends the Rosenbergs got the chair. The literary knight of Allende’s pinko Camelot, Dorfman in turn fled Chile after the 1973 coup, winning fame and sainthood by giving artistic form and international clout to the Latin American struggle against tyranny— in fact, all struggles against tyranny.

Purgatorio (through Nov. 26 at Seattle Repertory Theatre; 206-443-2222, www.seattlerep.org) is a sort-of sequel to his greatest hit, 1990’s Death and the Maiden, wherein a victim turns the tables on the man she thinks blindfolded, raped, and tortured her, which earned an Olivier Award (and Glenn Close a Tony) and went Hollywood with gravitas intact. In purgatory, a stark white hospital-like room with a white lamp on a nightstand next to a white bed, an unnamed Man in a doctor’s white togs hectors an imprisoned Woman to confess her sins to unseen cameras monitored by unheard authorities. Then they switch uniforms and roles, and Woman interrogates Man.

They turn out to be Jason and Medea—but the catch is, only the interrogator in each act knows this. In the afterlife, neither prisoner recognizes his/her questioner, whose job it is to get free of purgatory by wangling penitence out of the other.

So Purgatorio reprises Maiden’s internalization- of-the-oppressor theme, adding motifs of penitence and forgiveness partly inspired by Pinochet, the torture-happy, American-backed dictator who crushed Allende. Dorfman wrote Pinochet an open letter urging repentance, and the paradoxes of revenge and forgiveness have increasingly preoccupied the playwright after 9/11 and America’s resulting Talibanization. Rage is our blindfold, in life as in Dorfman.

Could a political play be hotter? In January 2003, top talents flocked to rebottle Dorfman lightning. Cool-kid producers announced the writer’s triumphant return to London theater with Catherine McCormack (Braveheart) playing Woman and Gael Garcia Bernal (Bad Education) as Man. Evidently these plans collapsed, as Seattle Rep director David Esbjornson staged its world premiere last week with playwright and Law and Order: SVU star Charlayne Woodard as Woman and Dan Snook, another stage-distinguished Law and Order vet, as Man.

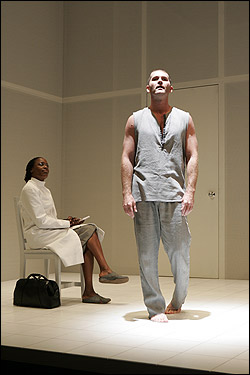

Even at roughly 90 minutes, the production is purgatorially long, and goes nowhere. The crimes of repression Dorfman publicized to the world gave Maiden a dramatic engine, but we can’t feel the same about mythical killings. There’s no menace in the interrogator, no tension between the two. Medea’s murders and Jason’s replacement dame are described, but without resonance; the dialogue is pallid as poetry and aimless as exposition. Snook’s acting is as solid as his well-exercised triceps, and Woodard is capable of greatness, but they’re thwarted by characters with hazy motives that shift from tender to vicious for no visible reason.

Now and then, good bits do occur. Man asks Woman what she most misses about life; she replies, “The sex,” and asks him what he misses most. “I’m not permitted to say,” he mutters. “Then it’s the sex,” she snaps. The audience chortled louder than the mild line perhaps deserved, out of deep relief over a vocal volley that makes a point and expresses character: her defiant sass, his prudish institutional poltroonery. Purgatorio intermittently makes satisfying sense, but it’s largely a mumbly muddle that can’t articulate its contradictions, let alone resolve them in any artistic pattern. The sight of the black Woodard under a white man’s thumb is shudderily effective visually, but the drifty text doesn’t develop its various racial/sexual/political ideas.

Dorfman, I think, is dragging in too much at once, in formless, overly free association. Besides Medea and Pinochet, he’s also musing over Cortez and his enslaved- then-spurned Native American lover Malinche. I wouldn’t be surprised if Woman and Man’s imprisoned plight somehow echoed Dorfman’s mother’s six-month mental breakdown and his own stint in a foster home.

“The relationships between therapist and patient, jailer and prisoner, of wife and husband are explored,” Dorfman told The Seattle Times’ Misha Berson. He murmured also of his interest in “questions of colonialism, and justice, vengeance, forgiveness, and memory.” Also, especially, “identity.” But his questions are vague and left unanswered, his explorations circlings in a fog.

It is an honor for Seattle to score so important a premiere by such a towering world-historical figure. Except for a few trivial opening-night verbal kerfuffles, every aspect of the production honors the craft. But Purgatorio needs further work— possibly an eternity’s worth.