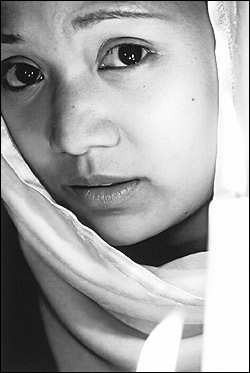

![]() Dead Woman Home

Dead Woman Home

East Hall Theater; ends Sun., Oct. 3

May Nazareno isn’t yet Anna Deveare Smith, but all evidence suggests she’s on her way. Like Smith, whose searing one-woman re-creations of complex social upheavals successfully challenge the popular media perceptions of such events, Nazareno here uses lucid solo performance to convey the private toll of a public tragedy.

On Aug. 19, 2003, a truck loaded with explosives drove into U.N. headquarters in Baghdad, killing 21 staff members and Sergio Vieira de Mello, the gentlemanly U.N. high commissioner for human rights who was in Iraq as secretary-general special representative. While de Mello’s dignified presence is felt in news clips (through judicious video design by Mark Ramquist), the focus in Dead Woman Home is not on him but on an ingenuous Filipina woman he inspired: 53-year-old Marilyn Manuel was de Mello’s devoted aide who, due to a bureaucratic error, was listed as a casualty in the bombing. Her mourning family in Queens, N.Y., assumed she was dead until, dazed, blinded, and in a hospital, she borrowed a nurse’s cell phone and called home to let them know she was, in fact, alive.

The incident, Nazareno knows, is an apt metaphor for the depersonalizing chaos endemic to the situation in Iraq, but she’s too smart to let any of it become simple agitprop; she’s determined to give the political circumstance human dimensions. Using various news reports and interviews she conducted as text, Nazareno inhabits each of the stunned participants—most effectively Marilyn’s shell-shocked son, Rick, and Lola, her baffled, angry, elderly mother—and diligently outlines their bewilderment, dovetailing it with the confusion Marilyn feels overseas. Better, Nazareno takes the time not only to illuminate the humanitarian reasons that would send a fiftysomething woman into the heart of international unrest, but to contemplate even the most violent insurgency from every angle. (“Wouldn’t you go to an uprising?” Marilyn asks us, after recounting the appalling living conditions in Baghdad. “I think you would.”) Nazareno and her dexterous director, Teresa Thuman, have been remarkably scrupulous in keeping every tiny moment of the production working toward shaping our understanding of the bigger picture.

They’re so scrupulous, in fact, that the piece can be a tad clinical. Only when Lola’s voice rises in horrified intensity after first hearing about the bombing does the production ever approach the sudden, unplanned urgency of real life. The show is completely professional but not as visceral as it perhaps needs to be; you end up admiring it more than you feel touched by it.

Still, you do admire it, and find yourself invested in its people—no small feat when a lot of artists think they have something to say about the war yet end up conveying nothing but earnest intellect. This is an adroit, accomplished plea for us to remember that inside every major tragedy are a million other dashed ambitions. STEVE WIECKING

![]() This Land

This Land

Richard Hugo House; ends Sat., Oct. 16

At crucial moments in our history, certain true, blue American voices have sounded out, imploring our tired and huddled masses to choose the path of righteousness rather than greed, of brotherly love and peace instead of stab-you-in-the-back bunkum. Count among those lonesome voices Woody Guthrie, the Okie troubador who spilled his dust-bitten folk songs across this land—”from California, to the New York Island” etc.—fighting to grant dignity to the forgotten, vilifying the bosses, begging adherence to simple socialist tendencies.

These past few years have seen a spate of biographies on Guthrie, texts mostly seeking to deconstruct and thereby humanize the heroic figure whose romantic mythologizing threatens to apotheosize him to Paul Bunyan status. Indeed, the first three or four numbers of Strawberry Theatre Workshop’s This Land, adapted, designed, and directed by Greg Carter, come perilously close to the sort of geriatric, gossamer-romanticized, NPR-ish, lefty feel-goodism we’ve come to expect from the nostalgic environs of Lake Woebegone (Carter developed the show with a troupe in Minneapolis). But stick around: The show, like so much of Guthrie’s own material, hides some sharp fangs behind its aw-shucks shrug, and is not afraid to snarl and bite at old-fashioned American chicanery and hypocrisy.

Conceived as an ensemble piece with the actors/musicians manipulating large, beautifully crafted, Bunraku-style puppets, the production is not so much about Guthrie as inspired by his gargantuan catalog of songs. Much of his best stuff is represented here: “Deportees,” “I’ve Got to Know,” “Waiting at the Gate,” and, of course, “This Land Is Your Land,” which anchors the show and is given a gorgeously haunting rendition. Each song is a skit, some of which are excellent and all of which deepen Guthrie’s vivid, elegiac lyricism. The show’s narrative is derived from the immediate content of individual songs, and the progress of tunes allows themes to emerge from Guthrie’s poetic and combative storytelling: the dignity of working folk, the heartbreak of love, the hell of war, the ravages of big business.

There’s a lot to grapple with here, but the music works to hold it all together. Like a locomotive, This Land gathers steam and momentum, and in the end becomes the finest of tributes to Guthrie’s legacy, as well as a handy reminder of the real roots of democracy in the power of ordinary people. And the songs, most of which are given simple, heartfelt renditions, are timelessly beautiful, full of rough-hewn grace. As America sometimes is. RICHARD MORIN

![]() Big Red Dance Company

Big Red Dance Company

Chamber Theater; ends Sat., Sept. 25

In a great deal of contemporary dance, the emphasis is on the momentum of the body careening through space or twisting around the fulcrum of another person. The influence of contact improvisation and release techniques have drawn us away from the taut lines of ballet or the deliberate distortions of traditional modern dance—which makes Kristina Dillard’s toes even more remarkable. Performing “bud,” an Isadora-like solo full of languorous sequences, it seems that she could just dissolve into a miasma of rose petals and silky costume, until you notice the precision of her hands and feet, the fingers poised and the toes spiraling in on themselves as she rolls across the floor. Dillard, who is returning to dance making with this Bigger and Redder program after a hiatus, has always had a quirky way with gestures, and now she’s using them almost like a painter uses a frame, to give edges and definition to the body onstage.

Some of these gestures come straight from traditional sources—the mudras of Indian dance, or the chiming of finger cymbals in Middle Eastern styles—while others feel more eclectic. In “lolalalalita,” performed by Joan Scott, they serve as a rhythmic counterpoint to spoken text from Nabokov’s Lolita, and as a kind of proto-mime, reinforcing the subtle feeling of unease in the story. Teresa Cowan-Kuist’s arm slashes like a serpent as she tells a story of a young girl’s self-immolation in “Untitled girl in blue”; the same shape wielded with a different energy benignly ticks off each item while Tesee Rodgers recites a list of colors in “Diebenkorn.” Dillard’s choreography here plays with the balance between large, space-eating phrases and calligraphic details.

First weekend special guests grace shinhae jun and her L.A.–based ensemble bk-SOUL brought several pieces with them that attempt to combine postmodern dance with martial arts and hip-hop. The dances are constructed very thoughtfully, but that seems to put them at odds with the underlying funk of the hip-hop sound score mixed by DJ shammy dee—they want to defy the rules while they fulfill them.

Dillard’s program, too, has some rough spots beyond the usual technical difficulties—the spoken text that accompanies several dances is muffled at times, and transitions between works can be hazy. But the obvious craft in the works, the contrast between dreamy voluptuousness and eccentric equilibrium, is part of a very specific—and potentially very exciting—dance intelligence. SANDRA KURTZ