In ninth grade history class I built a dam.

Just a little model—a diorama of the Grand Coulee—with its rhomboid face turning the flowing Columbia into a placid blue lake. Along the shore sat a row of houses and hotels pilfered from the family Monopoly set and glued into the plaster-of-paris hillsides. The surrounding desert landscape was painted irrigation green.

Even now, I’ll admit I find something aesthetically attractive about dams—they’re the only form of environmental destruction that can claim to be beautiful. Thousands of tourists go to see the elegant concrete curve of Hoover Dam each year. But who goes to see a clear-cut or a strip mine? As much as you may hate the salmon-killing potential of dams, you have to admire the form and elegance they often display.

Neal Bashor’s solo show at Gallery 4 Culture (Smith Tower, second floor, 206-296-7580; 8:30 a.m.–4:30 p.m. Mon.–Fri., through Fri., Aug. 27) betrays a similar fascination with dams—as impediments to flow, but also something born from an impulse to create, to alter our surroundings, to turn chaos into order.

There’s nothing polished or pretty about this assortment of conceptual sculptures and paintings. Bashor’s interest is in the idea of segmentation and restricted flows, not in creating an object of beauty.

The centerpiece of the show is an old clawfoot bathtub reworked and refinished with a partition across the middle. The tub is half-filled or half-empty, depending on your mood. It’s a clever piece that simultaneously winks at conceptual work of the past: Duchamp’s urinal and the Fluxus movement of the 1960s both come to mind. The water in Bashor’s tub is forever kept from the drain by the partition—an inconvenience for a potential bubble bather that mimics the more serious and fatal inconvenience facing migrating salmon on the Columbia and Snake rivers.

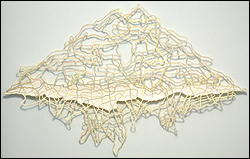

But Bashor’s art is much more complex than this one simpleminded analogy. In addition to the tub, there are small architectural models of swimming pools (inspired in part by his day job as a construction worker) sectioned off by Plexiglass. There’s a geometric formalism to these pieces—studies in how water can take on various shapes when held in suspension. You can’t help wishing Bashor would secure a grant to build one of these pools life-size, to see the effects of these partitions on a grander scale.

Then there’s the cute set of wine glasses with clear dividers set into them. Again, it’s a playful study in walls and division: taking an item of utility and turning it into something fragmented and unwieldy. I like to think of a group of urban professionals with stylish eyewear trying to sip chardonnay from these glasses, all the while complaining about rising energy prices.

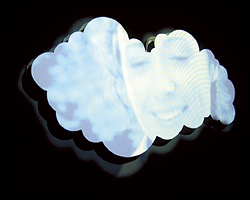

More literal in their exploration of these issues are Bashor’s small, mixed-media studies of dams on the Columbia, and a series of paintings inspired by those models. To call them literal is probably a stretch—these casts no more resemble the Priest Rapids or Rocky Reach dams than my ninth-grade project. Each model has a kind of feminine voluptuousness to it, as if the dams were diaphragms or dental dams, restricting flows of various fluids in a bodylike landscape.

In another series of small paintings called “Natural Disasters,” Bashor takes a large-scale natural event and diminishes it in his rendition. A mud slide, for instance, becomes a crude painting of a crude model of a mud slide. In another, a breached dam is reduced to a crashing wave. Entropy, these images imply, eventually overcomes our attempts to order chaos, whether it’s a dam on a river or a wall built on political divisions.

But none of this is overt in Bashor’s intentionally banal-looking art. He’s among a group of young local artists— including Dan Webb, Tyler Cufley, and Chris Grant—who revel in tacky railroad models and other intentionally artless ways of addressing the environment and other big issues. Much of the art in last year’s “What a Wonderful World” show at Soil Gallery approached nature in a similarly ironic vein: taking the sublime and reducing it to the substandard.

In this show, Neal Bashor’s dams may be ugly, but they succeed in allowing the ideas behind them to flow.