The focus of the fascinating, if unsettling, show at Western Bridge, “Crash. Pause. Rewind.,” is ostensibly America’s obsession with violent imagery. The gallery claims the work “looks at the disaster imagery generated by Hollywood and the news media alike as contemporary equivalents to the Romantic attraction to ruins.” Yet arguably, this nation’s bipolar attitude toward violence is more than just an idle infatuation.

“Crash” (through March 4; 206-838-7444, www.westernbridge.com) admittedly is not for everyone. But it prompts some important questions about how we as a culture accept and absorb horrific events. It features intense and provocative work by nine international artists.

Swiss artist Christoph Draeger’s 10-minute film loop of real and Hollywood disasters is almost too much to watch. In one segment, he lingers far beyond the normal attention span of the nightly news as he shows the Challenger space shuttle explode and twist in a ghostly ballet of disintegration, set to wrenchingly melancholy music. How many plane crashes can a person watch in one sitting? How numb have we become? Draeger’s film tests our resilience.

In a seemingly lighter vein, New York video artist Timothy Hutchings wanders through his own grainy black-and-white film, The Arsenal at Danzig and Other Views, like a bewildered Zelig visiting prewar Europe. It is cleverly made using postcards of once-grand European edifices, with Hutchings digitally superimposed onto them, waving awkwardly at the camera. But the buildings frozen in these postcards no longer exist—humans meticulously built them and just as ingeniously destroyed them during two devastating wars. Through this quaint and impossible act, Hutchings creates a naive travelogue that is unexpectedly heartbreaking.

Jon Haddock demonstrates how our culture regularly confuses reality and entertainment by taking a series of violent moments in recent history—the murder of Martin Luther King Jr., the L.A. beating of Reginald Denny, or the horrifying cafeteria prowl of the gun-wielding Columbine kids—and disguising them as digital images in the jarring style of video games. Mixed in the series are also a few scenes from movies, which aren’t really necessary to make his point.

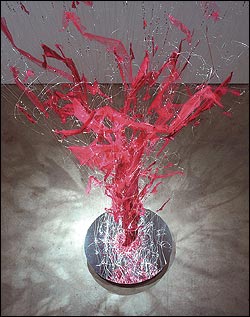

New York artist E.V. Day’s Cherry Bomb Vortex, a torn whirlwind of a red sequin dress, gloves, and hair snippets reflected over a mirror base, evokes a bloody explosion of a woman. Violence against women is a huge subject in itself, and to see it depicted in such an eye-catching way highlights the hypocrisy of all of us who decry it but can’t look away.

Chris Larson’s wood reconstruction of the car from the Dukes of Hazzard TV show crashing into the Unabomber’s cabin is the biggest installation in the exhibit and was perhaps the most time-consuming to construct. Yet, it makes a fairly simple point about the American penchant for merging fantasy with reality in search of a happy ending. This piece feels almost outdated, however, as the Ted Kaczynski story of 1996 has been usurped by far greater acts of violent madness since then.

As a culture, we treat violence lightly, yet when it happens to us for real and on a large scale—9/11, the Iraq war, Hurricane Katrina—we have a hard time knowing how to process it. Clearly, we still haven’t recovered from the gaping wound inflicted by 9/11. For this reason, the most powerful image in “Crash” is also the most simple: Euan Macdonald’s almost childish line drawing of two airplanes on a piece of white paper, flying in a direct path toward one another. Though he sketched it back in 1998, there is no way to look at that image now and not feel unease, despair, and, worst of all, horrible familiarity.