ARGUABLY THE PREEMINENT, and inarguably the most active, opera composer of our time is Philip Glass. A Contemporary Theater scored a coup by commissioning his latest project, a setting of Kafka’s In the Penal Colony. This 1914 short story is a bleak dystopian fable about a prison with a unique method of execution: a mechanized bed of needles that writes onto its victim’s body, in torturous script, whatever law he broke. Glass’ librettist Rudolph Wurlitzer adapted it for two singing roles: the Officer, who’s obsessively devoted to the colony’s unseen Old Commander (the machine’s inventor) and wants to keep this form of punishment going; and the Visitor, who comes to observe the machine and may or may not have the power to discontinue its use.

In the Penal Colony

A Contemporary Theater ends October 1

Most of the 90-minute, one-act piece is a not-too-graphic description/demonstration of the machine—a sort of creepy Tales from the Crypt anecdote stretched fairly thin. Kafka himself, played with dapper, feral intensity by Jose J. Gonzales, appears as a character in the opera; there’s some implication that the action of the plot and/or the writing of the story is a masochistic fever dream of the self-pitying, self-loathing Kafka—a writer’s hallucination of writing as a punishment.

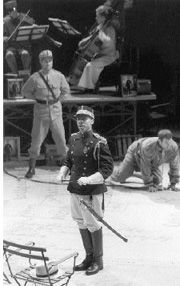

John Conklin’s set is dominated by the execution machine, a giant gear-laden scaffold shrouded in gold plastic. JoAnne Akalaitis directed, and Pat Graney devised the stylized movement choreography, with characters often echoing each others’ gestures. Both Herbert Perry as the Officer and Kenneth Gayle (filling in for John Duykers) as the Visitor sang quite convincingly; nonspeaking roles were taken by Matt Seidman as the condemned man and Steven M. Levine as a prison guard.

A STRING QUARTET plus double bass serves as the orchestra for this chamber opera, and the Metropolitan String Ensemble plays warmly. Glass’ music features his familiar love-it-or-hate-it style—oscillating broken chords, pure triads, rich but not obtrusive textures. It’s an idiom that’s proven flexibly effective for any operatic subject he’s chosen, but it had a special sly appropriateness here, as an accompaniment to a story about a relentless machine. And it serves beautifully as a background for voices; I think Glass’ great strength as an opera composer is his skill in text setting. Not a syllable was unclear, with the naturalistic speech rhythms of the vocal lines bouncing off the neutral, chugging accompaniment. Glass, benefiting from a quarter-century of theater experience, knows when dialogue needs to be gotten through with minimum fuss and maximum clarity—as opposed to the school of post-Menotti opera composers who attempt to stretch painfully artificial lyrical flights out of “Please pass the salt.”

And yet Glass’ score does sometimes cross the border between experienced craftsmanship and lazy formula. There’s something very baroque about Glass’ operatic output—something akin to the early 18th-century system, in which the opera world’s constant demand for new product required from popular and busy composers like Handel a rapid, businesslike, if-this-is-Tuesday-this-must-be-Partenope approach to production.