Camino Real hasn’t played in Seattle since 1972. There’s good reason for that. It’s no cakewalk. Notoriously hard to stage and difficult to decipher, Tennessee Williams’ midcareer caterwaul is a bitch of a play from all angles. After its 1953 premiere in New York City, Times critic Brooks Atkinson sounded a caveat to potential audiences: “Looking into the corners of his heart, Tennessee Williams has written a strange and disturbing drama. . . . People who say that they do not understand it may be unwilling to hear the terrible things it records about an odious no-man’s land between desert and sea.” One can almost hear Atkinson elegantly clearing his throat in high-minded tolerance.

Those terrible things we may be unwilling to hear come across in Camino Real (through Saturday, Dec. 3, at East Hall Theatre; 206-325-6500, www.ticketwindowonline.com) as a howl of pain, a desperate plea for sanity in a world given over to gimcrack materialism, false illusions, and the everyday murder of hope. There was no shortage of this kind of thing among American writers during the Cold War; it’s not so much what Williams says as how he says it that many found so objectionable.

Llysa Holland, co-founder of theater simple and the guts behind this particular production, is well aware of the risks involved in mounting Camino. “From the first time I read it in college, it was introduced as a problematic play that audiences didn’t get,” she writes in the production notes. Part of that problem is purely compositional. Sandwiched between A Streetcar Named Desire (1947) and Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (1955), two acknowledged masterworks of psychological realism, Camino Real is a bilious gush of pure fantasia, a fragmented, highly uneven descent to the nethermost reaches of psychic despair. Its form is abstract, self-conscious, and at times, almost willfully incomprehensible. Williams, a genius of exposition, here plays with the signposts of narrative, one minute drawing attention to his technique only to subvert it the next. As in the plays of Beckett or the films of David Lynch, the author asks nothing short of unconditional surrender to the idiosyncratic logic of the dream. However, much of what infuriated and confused Camino‘s early critics looks downright quaint to audiences well-versed in the stuff of postmodernism. The real problem lies elsewhere.

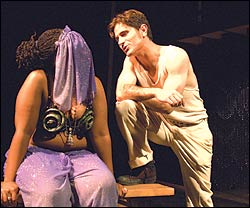

Directed by Carys Kresny, theater simple’s production gives us a bare arena, all darkness and hard angles, a plaza with a balconied building on each side and a dried-up fountain at its center. Through this existential dead end wanders a richly diverse cast of wayfarers, including Don Quixote (John Wray), Casanova (Andrew Litzky), Lord Byron (Brandon Simmons), and Kilroy (Ricky Coates), a punch-drunk boxer with a golden heart “as big as the head of a baby.” The inn is run with sniveling, fascistic glee by Mr. Gutman (James Cowan), a potbellied voluptuary and two-bit tyrant whose narration stitches together the “16 blocks” that make up the structure of the play. Though the script’s tone is by turns elegiac and furious, and despite the stark, abstract setting, Kresny opts to give Camino Real a circuslike atmosphere, seemingly intending to eke out of Williams’ sadsack menagerie something akin to Fellini’s 8½, where each parading figure becomes a stand-in for the author’s divided consciousness. It’s an interesting idea, giving the early scenes an antic energy, but it also robs the play of intimacy. Where there should be claustrophobia, there is entropy, a scattering of sincerity. Rather than enhancing the play’s sense of loneliness and loss, this diffuseness only distances the audience; it becomes hard to find a point of focus. With nothing to grab one’s attention, this Camino quickly becomes a blur of nihilistic screeds, flights of fancy, bad puns, and pratfalls.

A bigger problem—a fatal one for this production—concerns Williams’ language itself. Camino Real contains passages of excruciating beauty, moments that plumb the sad poetry of “the sweet used-to-be,” but the cast demonstrates little feel for the cadences of Williams’ despair. Wray is solid as the aging, despondent Quixote, and Cowan digs delightfully into Mr. Gutman’s nastiness, but most of the rest seem altogether too young and bright to be saying the things they say. No one really steps up to wrest possession of their role. Whether this is a matter of intimidation, over-reverence, or (understandably) not understanding the material, the results are the same. Such sweet cynicism in the mouths of babes sounds like so much undifferentiated poesy, voluble but flat. It’s probably better that Kilroy was here than not; one just wishes he were more here.