Artistic bloodlines really seem to matter in modern dance, and in this weekend’s performances by the Chamber Dance Company (Thurs., Feb. 3–Sun., Feb. 6, at Meany Theater, University of Washington; 206-543-4880) we can see a part of that family tree laid out in a series of four works—an ancestor and three descendants. Martha Graham’s 1931 Primitive Mysteries is the lodestone for the rest of the program and was the catalyst for director Hannah Wiley.

“I had seen this when I was in grad school, and I was stunned by its simplicity and its audacity,” says Wiley. “Of all her work, it’s my favorite. When I decided on [it], I was interested in rituals—how they are the same [between cultures], how they’re different, and how they change. And I was looking for her legacy, people who had studied with her or had close associations with her.”

The ritual aspect of the Graham work is fairly blatant. A phalanx of women stalk onto the stage, surrounding a soloist in white who skips and jumps around them, blessing them as they lurch fiercely. It’s based on Graham’s observations of Southwest Indian ceremonies re-enacting the Crucifixion, which were an important turning point as she developed her dance technique and choreographic style.

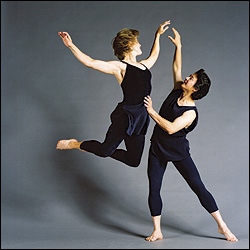

How those ritual elements have been translated in her artistic descendants varies. Elisa Monte was a leading dancer in the Graham company for several years, and her Pigs and Fishes, from 1982, shares that intense physicality but is a much more complex construction. Wiley believes that the piece, with a score by Glen Branca, “is definitely ritualistic, unlike the Graham, which is a ritual. [The Monte piece] is totally abstract. There’s no linear or narrative thing in it.”

Beat, by Mark Dendy, whose Graham training has been filtered through his snarky sense of humor, is a wry commentary on the fitness culture of the 1980s, when it was made. But within his sly send-up of Richard Simmons is one of the elements of ritual behavior—a shared physical experience. As four dancers lope across the floor, panting while they shout out the peculiar cadence calls of aerobics classes, their gym shoes squeak in unison.

The final work on the program, Hannah Kahn’s 1979 Ring, approaches ritual in a more private realm, according to Wiley.

“I have a story that I think is going on, but I’m not going to say it out loud,” she says. “I think it’s a flashback. It’s totally emotion-filled for me, and I think it’s about the rituals of love.”

Of the four choreographers on the program, Wiley thinks that Kahn is the one who is currently the most overlooked.

“Kahn worked intensely with [Anna] Sokolow, who was in Graham’s early company, and [Kahn] studied Graham technique at Julliard,” she explains. “I think [Kahn] was one of the most innovative choreographers of her era. In the ’80s, she was blowing people’s minds. You can see a lot of her influence in [Mark] Morris, who danced with her before starting his own company; you can see where he got some of his ideas. Her belief in the power of conveying abstract thought through dance—she was a believer in that power.”

The family relationship among these artists does seem to come through in the movement. When Wiley first put this program together, she says, “It was all coming together in a very tidy package. We had the ritual thing, we had the connection of styles and pedagogy, and then the strangest thing happened: The first time I had a run-through of all four dances, they all had this gesture in them [a bent arm sweeping across the body], and I thought, ‘OK, that’s kind of heavy-handed. It could be a fluke.'”

It didn’t feel like a fluke, though.

“It gave me pause, because it is a pretty stylized action,” Wiley muses. “But it’s symbolic of how [Graham’s] influence lives—it’s a little kernel of it, but it’s in those people’s bodies. You take the early modern works and the late works, and to get from one to the other all this stuff has to feed in on a physical level through different bodies and different people. Every time, you’re likely to come up with a serendipitous ‘Aha!’ That’s how those things come together.”