Oscar Wilde once wrote, “The only excuse for making a worthless thing is that one admires it intensely.” In his solo show, “Sculpture” (at Greg Kucera Gallery through June 25; 206-624-0770), Drew Daly demonstrates that he knows a thing or two about transforming useful things into elegant, worthless objects. The results are supremely admirable.

The 2004 University of Washington MFA graduate is on a fast track to success, and this brilliant debut show demonstrates a Houdini-like ability to perform the impossible. Most of the pieces involve utilitarian ready-mades—furniture, doors, or particleboard plywood. Through hours of painstaking work, Daly conjures things of rough, delicate beauty.

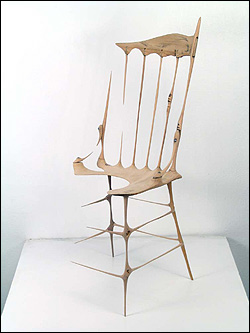

The work Subject: Remnant is the emblematic piece of the show. In sanding an antique Windsor chair for 300 hours, Daly has created a shadow, a skeletal ghost of the original. It’s a phenomenal artifact: Only the slightest wisps of legs and frame are left, barely enough to support itself, much less someone’s bulky posterior. All of the original chair, however, is on display: Daly carefully saved every ounce of sawdust and has piled it in a corner and traced the imprint of a chair in that dust.

Sculpture is often about reduction and removal—the art of destroying a block of marble, for instance, to find something unique locked inside. What Daly has accomplished with hours of seemingly pointless labor—like a convict digging out of his cell with a plastic spoon—is to pull off feats of magical proportions.

That magician’s touch is evident in a series of modified Adirondack and other wooden chairs, their slats meticulously split and pulled apart. Daly has created two chairs from one, and where the fragmented wood is left to form its inverse twin, Daly has painted that section to remind us of the loss. It’s splitting matter to create a fragile, more pleasing pair than the original. In Drew Daly’s mathematics, one plus one equals much more than two.

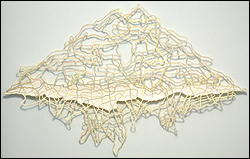

Other destruction-constructions are more quixotic and seemingly pointless. Several wall sculptures consist of carefully disassembled 2-foot squares of particleboard plywood, painted and rearranged and reassembled in a puzzling maze. Daly carefully documents the process, turning the work of the work into his subject. Alongside each sculpture, a blueprint of the disassembly-assembly records Daly’s compulsive act. It reminds us that all of the stuff we live with— the wood in our homes, the coffee cup on the desk—is the product of some kind of work, whether the slow, chaotic growth of a tree, the mechanized chipping of a sawmill, the detailed carving of a furniture craftsman, or the repetitive efforts of a factory worker in the developing world.

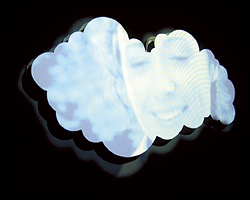

Other pieces involve cut and doubled photographs, most of the artist himself. They are split and fragmented, pixilated—almost unrecognizable. Ghosts of the originals, however, remain.

Much of the power of this work rests on absence: One of Daly’s molded sculptures traces in three dimensions the shadow of an end table on a wall. Another sculpture sketches a table using a web of metal wires. What’s fascinating is that these pieces succeed as intellectually rich conceptual works but also as accessible and pleasurable treats for the untrained eye. You can talk endlessly about Daly’s notions of deconstruction, mirroring, and negative space. Or feel free to simply say: “Wow, two chairs from one . . . cool.”

Artist lecture and discussion: noon Sat., June 4, at Greg Kucera Gallery, 212 Third Ave.