THE PENSIVELY HIP Chicago artist Inigo Manglano-Ovalle visited the Henry recently to explain his show “Banks in Pink and Blue,” which features one pink and one blue cryogenic tank containing -321 degree liquid nitrogen (refreshed biweekly) and live sperm (some of it donated by famous artists). The show deals with ideas of genetic ethics, particularly the question of ownership. Mr. M-O cited the current Australian case of a couple who froze their fertilized eggs, died in an accident, and left behind a big estate and a big question: Does the estate own the embryos, or do the embryos own the estate?

Banks in Pink and Blue

Henry Art Gallery through April 16

The artist created a corporation to which donors signed over their sperm for storage; the contracts, bristling with legalese, are posted on the wall. He sardonically referred to the notion of “the corporate body, faceless, but yet a body.” So the sperm are protected by a body—just not the kind of body nature had in mind. His corporation is a work of art that questions the humanity of corporations.

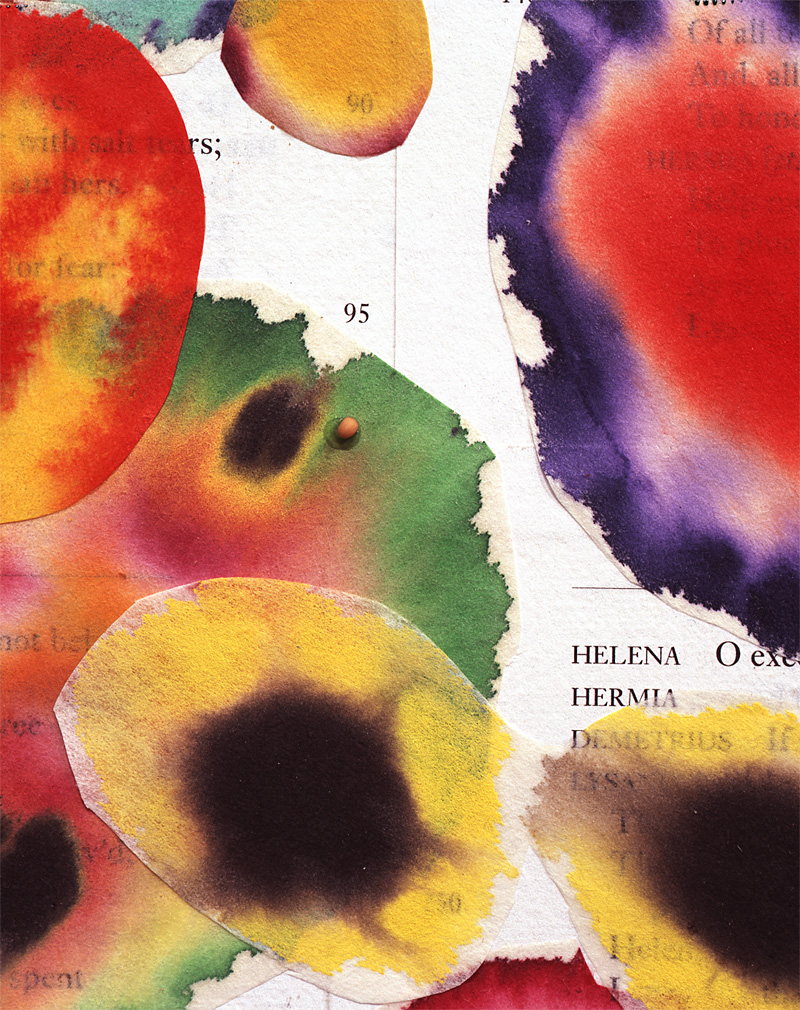

The installation also features a videotape sequence of images: fluffy clouds in fast-forward, a floridly sexual hibiscus, and gloved hands placing samples in the tanks. All of this is accompanied by a soundtrack of a woman intoning the contract terms between the sperm “lenders,” the artist, and the gallery. Manglano-Ovalle said, “[Her] soothing voice is to keep you there.” Faced with a lot of dry reading material and minimalist tanks, some folks might take one look and leave. Andy Warhol’s comment about his movies comes to mind: “If it moves, they will watch it.”

The video is not just a pragmatic tactic to keep the gallery from emptying. It represents a piece of creation in the sacred sense, of heaven and earth, a glimmer of something bigger than the artist’s cleverness and the feats of the scientists he collaborated with. It taps into larger issues and contrasts with the absolutism of the science, the certainties of legal rhetoric, the coldness of the work. The work is about the fear of institutions and technology tampering with creation, and that image of sky speaks of fear in a subtle way. It rescues the work from being just about the cult of the artist and the propagandistic head trip of his theme. It adds emotion, depth, humanity—even potency.

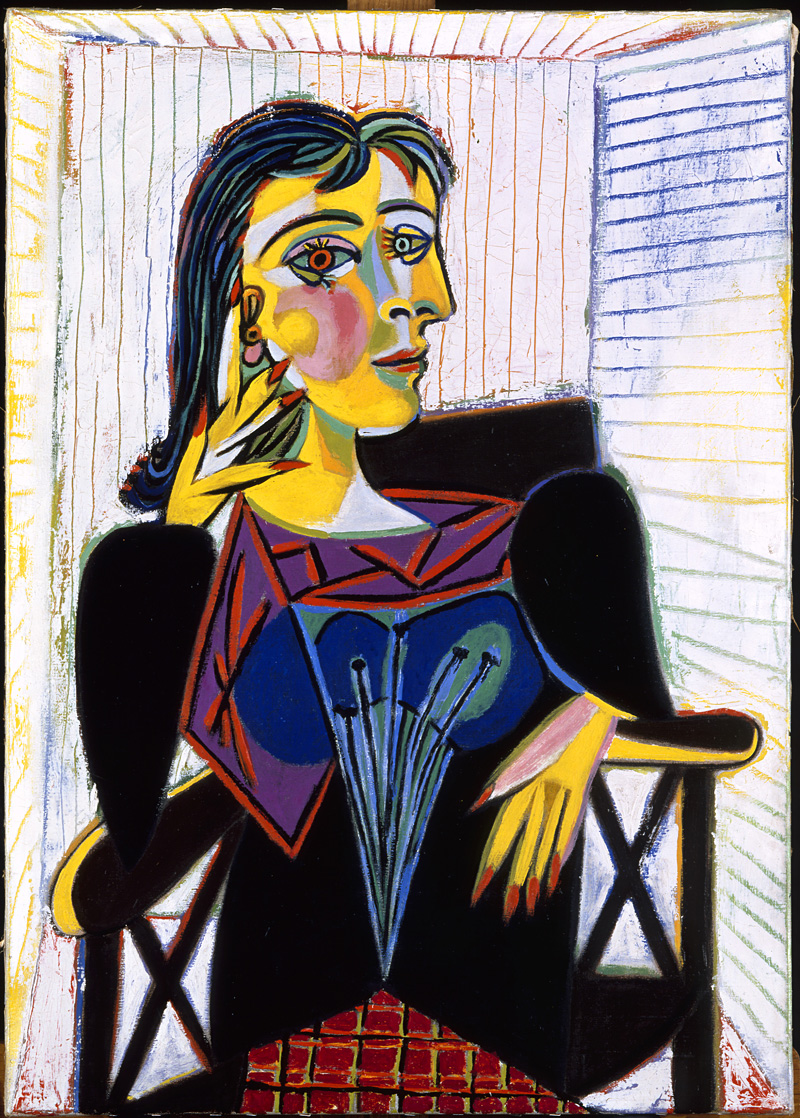

Though it certainly raises the most important questions, “Banks in Pink and Blue” is somewhat hampered by its self-important, judgmental quality, a kind of graveness that left me craving some humor. (Hey, what if you took the artists’ sperm and fertilized those supermodel eggs on the Internet? You could create the ber-artist, a 6-foot tall Picasso who looks like Linda Evangelista!) Science is capable of conscience too, after all: UW assistant attorney general Lisa Vincler, speaking on the panel with Manglano-Ovalle, noted that two percent of the Human Genome Project funding goes to genetic ethics research.

Manglano-Ovalle succeeds in provoking debate about a complex topic, moving it out of its political and scientific context into the world of art. But an important topic does not an important art work make. Picasso’s Guernica is important, for example, not because the bombing of Guernica was important but because of the emotions it taps in both the artist and viewer. Manglano-Ovalle’s Henry show does best not when it’s making cold, ironic, intellectual points, but when it evokes fear and awe—when the artist dares to feel, not preach.