Amir and Emily are a model Manhattan couple. He is a mergers and acquisitions attorney and she is an artist. Of course, for the purposes of Disgraced, those roles are somewhat secondary to the fact he is an American-born Muslim and she is white. The same goes for the guests that the couple is entertaining in its posh Manhattan apartment during Ayad Akhtar’s Pulitzer Prize–winning play: Isaac is a Jewish art dealer, Jory his African-American wife and Amir’s colleague. Yet it is their roles in the real world that transform the dinner party at the center of this one-act into an assymetrical battlefield of identity and ideas.

The catalyst of the conflict comes when Emily and the couple’s nephew Abe convince Amir, a former public defender, to meet with an accused terrorist. After the meeting, Amir is quoted in The New York Times, drawing unwanted attention from his firm’s partners that threatens an identity carefully constructed to distance Amir from his Muslim faith. Meanwhile, Emily has been meeting with Isaac regarding an art show for a collection of pieces inspired by Islam. And so when the two couples with complex and overlapping relationships and alliances get together for dinner, a drunken debate erupts.

This isn’t the usual finger-pointing that marks such discussions in contemporary America, though. Isaac and Emily are eager to celebrate the aesthetics and theology of Amir’s faith, and it’s Amir—fueled with too much scotch and rife with the internal conflict of a man who has changed his last name to hide his ethnicity—who endeavors to educate them about the evils of Islam, going so far as to call the Koran “one very long hate-mail letter to humanity.” It’s an uncomfortable moment, for the diners and the audience.

It’s not the last, as Akhtar’s script forces all his characters to confront the contradictions of their belief systems, resulting in an explosion of unease. In a thorough debate, they address everything from airport security to the difference between hijab and niqab. The discussion meanders to talk of the meal and their families, bringing the proceedings both levity and humanity. Yet this script does not pull any punches on the topics of ethnicity and race; thus the tension, always there, in the corner, awaiting the next round.

In the writing, as exquisite and intricate as a Turkish rug, Akhtar fiercely manipulates stereotypes, creating a cognitive dissonance that forces the audience to examine its own assumptions. The effect is uncomfortable and enlightening. Yet the action isn’t weighed down with hard truths; director Kimberly Senior—who directed this play through its 2012 Chicago premiere and subsequent Broadway run—does not barrage her audience with these big ideas. Rather, she masterfully draws out the humor in Akhtar’s multifaceted, unrelenting, ever-unpredictable script.

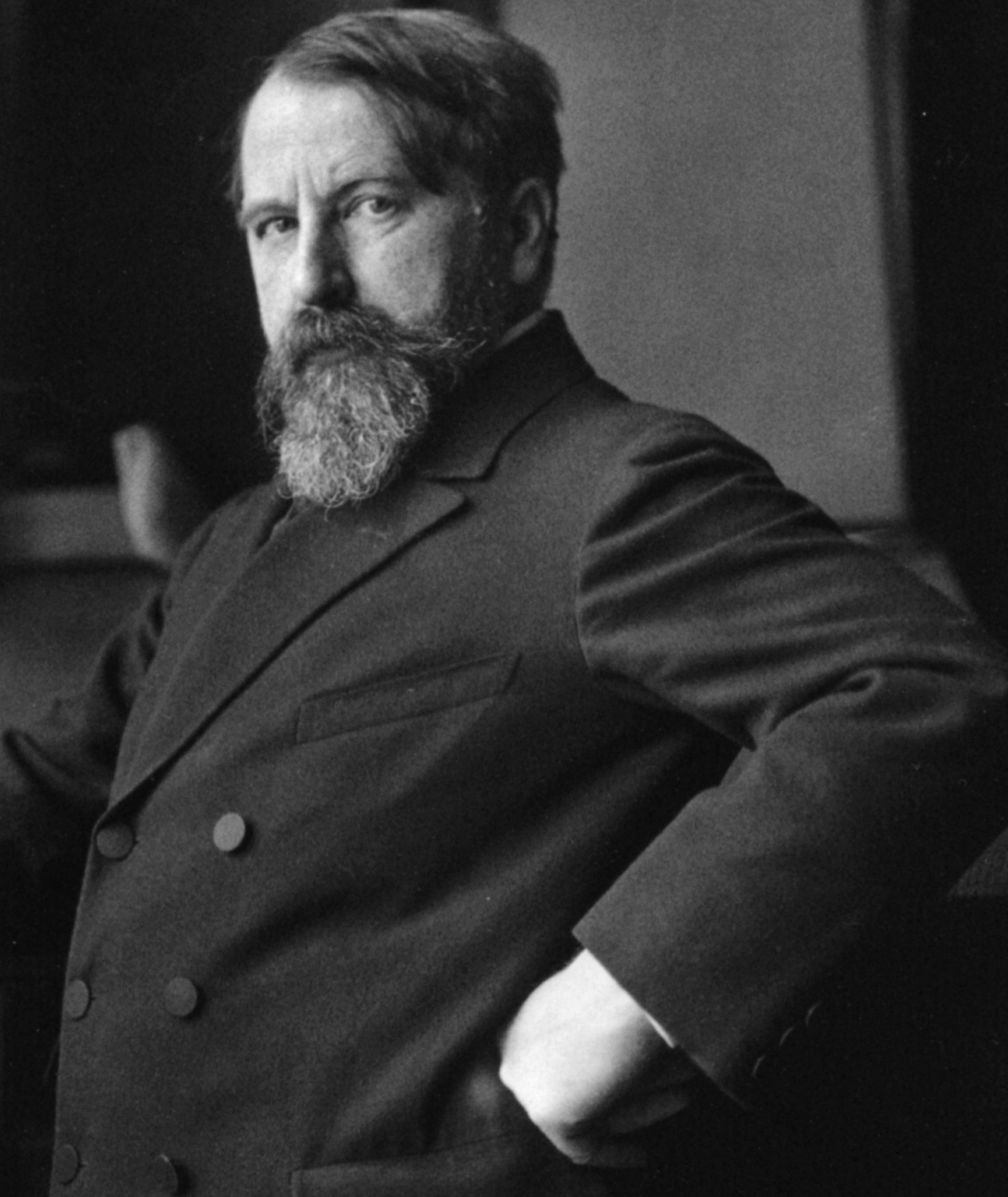

The cast of five

delivers evocative performances while delightfully dancing among comedy, thriller, and tragedy. Each character brings his or her own cultural biases, which can align and diverge in a rhetorical flash. For instance, “open-minded” liberal Isaac (J. Anthony Crane) exalts Islam until the issue of Israel arises—though not a Zionist, he doesn’t agree when Amir defends certain acts of violence in the Gaza Strip. It’s a shocking declaration from Amir (Bernard White), whose inner conflict makes him a sympathetic character though he’s a denigrating dick throughout the play.

The rest of the cast is similarly complex. Artist and devoted wife Emily (Nisi Sturgis) balances grating gullibility with excruciating emotion as she strives to please her husband and advance her career. As an African-American woman, Jory (Zakiya Young) has overcome her own hurdles and has her own secrets. Amir’s nephew Abe (Behzad Dabu) embodies the optimism and angst of youth.

The hopeful nugget at the center of Disgraced is that these discussions can happen—if not at our own dinner parties, where we are perhaps better at disguising our own discrepancies, then in the theater.

Seattle Weekly covers all the arts, from books to film to dance. If you know something we should know, e-mail arts@seattleweekly.com. Follow us on Facebook and Twitter.