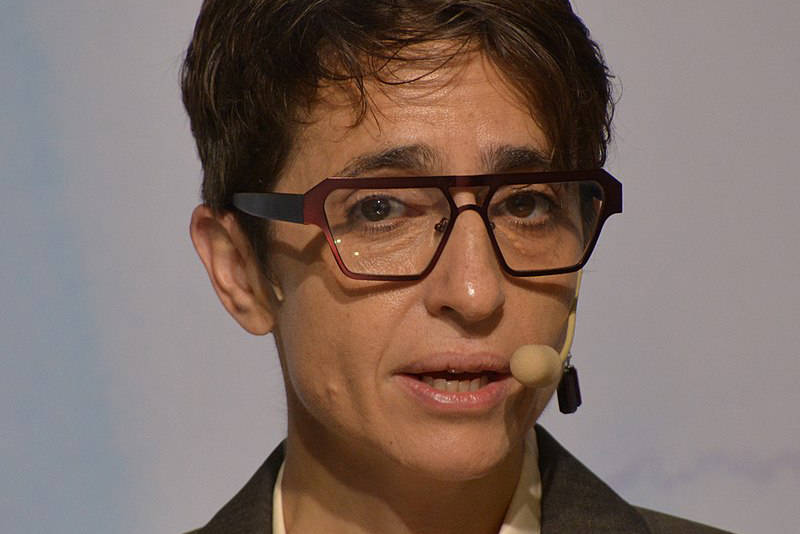

Consider: A stranger calls you on the phone, says she’s conducting a survey, and asks if you believe in God,” Lesley Hazleton writes near the beginning of her new book. “You can answer only yes or no, since ‘don’t know’s don’t count. And consider too that if you simply hang up, as you’re likely to do if you consider this an absurdly simplistic question, you don’t count either.” Hazleton is explaining why polls usually indicate that Americans are such devout believers in God; if you force someone to make a binary choice, all nuance and shading simply disappears. Hazleton has never been a fan of oversimplification, which is why she wrote Agnostic: A Spirited Manifesto.

Agnostic (out now on Riverhead Books) is a beautiful, inquisitive, energetic 200-page tribute to uncertainty. It’s a book only Hazleton could write, a densely researched exploration of the agnostic position that’s about 50 times as charming as anything Sam Harris has ever written and 500 times more inspiring than any of Joel Osteen’s books. Along the way, she employs examples ranging from Muhammad’s terrified reaction to the first Quranic revelation to a physicist who discovered that adding every number from one to infinity equals -1/12 (yes, minus one-twelfth). And after you’re reeling from the anecdote about the time Hazleton almost died in a racecar crash, she then coolly explains why mortality is vastly preferable to immortality in precise, compelling language. You might give yourself windburn turning these pages.

As a lifelong atheist who has many problems with blowhardy Hitchens-style atheism and who rejects outright the moronic hatred of Dawkins-style atheism, I still approached Agnostic with some trepidation. The word Manifesto in the title is a bit off-putting; it implies that Hazleton wants to force a pamphlet into your sweaty palm. I enjoy reading beautiful writing about faith, but there’s usually that uncomfortable moment when The Ask arrives: when the author makes uncomfortable eye contact and clears her throat and starts to offer a really sweet deal on a time-share on the other side of the Pearly Gates. How uncomfortable could Lesley Hazleton’s agnostic version of The Ask be?

Thankfully, that moment never comes. In fact, “manifesto” is by far the worst, most poorly chosen word in this book. She’s not demanding you denounce atheism, or Jesus Christ (or Allah, or Bob, or Tilda Swinton, or whoever) as your lord and savior. She mostly just wants us all to sit on a big blanket with her on a dark hillside and look up at the stars for a while. The one point to which Hazleton keeps returning in Agnostic is resistance to the idea of complete understanding. Several times she refutes the idea of a meaning of life. She highlights the importance of uncertainty in science, using the two great jesters of physics, Einstein and Feynman, as supporting evidence. She does not demand that the faithful give up their religion, but she does think people should embrace the ineffableness of it all:

“If there is one thing that can really be said with any certainty about God, it is that the name is utterly insufficient to the concept. What, then, if we were to refrain from laying claim to it? What if we were to drop the pretense of familiarity, the hubris of claiming to know the unknowable and trying to nail down the transcendent? What, that is, if we were to leave God out of the discussion—not as a matter of disbelief, but in full awareness of the insufficiency of the name, and in acknowledgement of whatever it is that we sense it might stand for?”

When I finished reading the last page of Agnostic, I closed the book and stared at it for a while. Hazleton’s voice bounced around in my head, repeating her sparkling anecdotes—about an elegant mathematical proof she carried around in a wallet that was later stolen, about a night she spent on Mount Sinai, about the mezuzah on the door of her houseboat. And then I did something I have not done in a very long time: I flipped the book over, opened it, and then read the whole thing over again immediately. I didn’t want to stop feeling that joyful crush of wonder, of not knowing. When you acknowledge the uncertainty that surrounds you at all times, that means there’s so much more out there for you to learn. In fact, that’s when the fun really starts. E

books@seattleweekly.com

Paul Constant is the co-founder of The Seattle Review of Books. Read daily coverage like this at seattlereviewofbooks.com.