Adore

Opens Fri., Sept. 6 at SIFF Cinema Uptown and Sundance Cinemas. Rated R. 110 minutes.

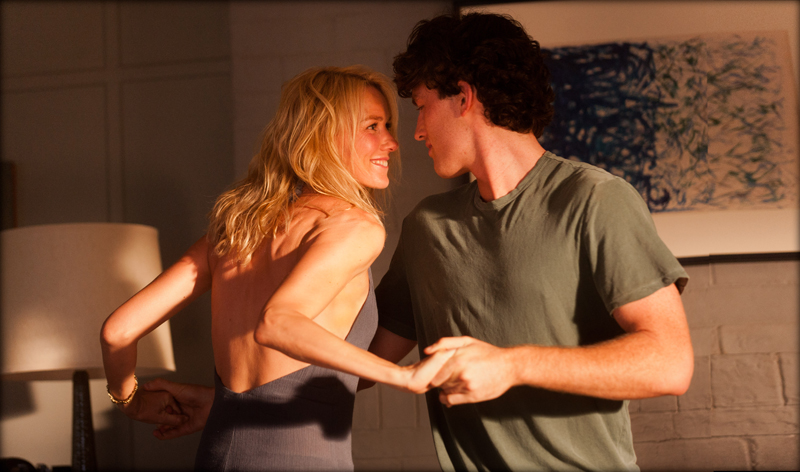

There are worse reasons to see a movie than the spectacle of Naomi Watts and Robin Wright sunning themselves in bikinis on a raft, each accessorized with a buff young Australian stud. Called Two Mothers when it screened during SIFF last spring, this adaptation of a Doris Lessing story tantalizes with its Oedipal displacement: Each mother begins a fling with the other’s 18-year-old son. It’s totally inappropriate, but not quite incest. Then, by mutual assent, these covert affairs drag on for years (and I mean drag). Fathers are mostly absent from the melodrama: One’s dead, leaving Lil (Watts) a widow, and the drama-teacher spouse (Ben Mendelsohn) of Roz (Wright) soon departs the scene.

And what a scene it is. Filmed in a beach colony overlooking the Tasman Sea north of Sydney, the movie is full of pounding surf and golden sunsets—like the jacket art for a romance novel. The heaving tides and musky suntan oil practically demand transgression, and neither woman seems inclined to resist. (The sons, played by Xavier Samuel and James Frecheville, don’t figure much in the decision-making; lounging around shirtless and available is their primary function in the plot.)

Are Roz and Lil fools, predators, MILFs, or what? Adore never really gets a handle on their behavior. English screenwriter Christopher Hampton (Dangerous Liasons) expands the timeframe from Lessing’s 2003 novella Two Grandmothers, and French director Anne Fontaine (My Worst Nightmare) is nothing but generous toward her two stars. Both look great in one of the rare movies to be shot in 35 mm film these days. But the story only unfolds from shock to acceptance to soap opera. It needs to get smarter after the initial sex, but the opposite happens. Watts and Wright are left with exchanges like “What have we done?” “Crossed a line.” Yes, ladies, we can see that—now what are you going to do about it? That question really applies to Hampton and Fontaine, and they don’t seem to have any idea. With all the swimming and surfing, I kept hoping for some sharks to attack, but they sensibly stayed away. Brian Miller

Afternoon Delight

Opens Fri., Sept. 6 at Pacific Place and Sundance Cinemas. Rated R. 93 minutes.

The Starland Vocal Band is nowhere to be seen (or heard) in Afternoon Delight, so there’s another lost opportunity for the ’70s one-hit group to come back. This Afternoon Delight has more serious fish to fry, even if it’s full of strong comic actors. The movie is arranged around Kathryn Hahn, who—whether parachuting for the length of a story arc into ongoing series such as Parks and Recreation or cutting a bizarre path through Step Brothers—has been threatening to bring her particular brand of funny/weird to center stage for the best part of a decade.

Hahn is allowed to make her mark, and then some, in Afternoon Delight as Rachel, a stay-at-home mom whose disenchanted life is shaken by her encounter with an exotic dancer, McKenna (Juno Temple), during an evening when she and husband Jeff (Josh Radnor, from How I Met Your Mother) double-date with friends at a strip club. (Couples in movies have been known to do this.) McKenna is soon staying at Rachel and Jeff’s place, an awkward situation complicated by McKenna’s sideline as a prostitute. Writer/director Jill Soloway would have us believe that Rachel’s mid-life crisis might accommodate all this and more, and maybe in a better movie it could. Soloway does her best to remind us we’re not watching a pure comedy, as she regularly includes scenes of idle boredom and cringeworthy behavior.

If the film works at all, though, it’s because of the comedy. Anytime Hahn is let off the leash—for instance, at a hen party where she tipsily insists on toasting her friends while staring soulfully into the eyes of each—she’s all skyrockets in flight. There’s also Jane Lynch, stealing a few typically crisp moments as Rachel’s oversharing therapist, and the splendid Michaela Watkins and Jessica St. Clair as friends whose personalities roughly fit the molds of Fran Drescher and Chelsea Handler—though each actress is distinctive enough to break those molds.

As funny as its isolated moments can be, Afternoon Delight opens too many cans of rubber snakes. Soloway seems to be aiming at the kind of observational groove that Nicole Holofcener and Lisa Cholodenko get in their films, but with some Judd Apatow stirred in. The mix doesn’t quite become Jell-O, and it’s further proof that the plot device of the soulful striptease artiste deserves a break from contemporary movies. Robert Horton

Drinking Buddies

Opens Fri., Sept. 6 at SIFF Cinema Uptown. Rated R. 90 minutes.

Workplace romance is always a fraught subject, and the water-cooler flirting that seems so fun at the office can crash into hard reality after happy hour. Working at a Chicago microbrewery, the amiable bearded Luke (Jake Johnson) can afford to kid around with colleague Kate (Olivia Wilde) because both are protected by the firewall of being in a relationship. We’re only kidding about you being so hot and me being so horny, because we go home to someone else—right?

Things aren’t so clear in Luke’s mind, however, and Kate’s relationship with the older, more affluent Chris (Ron Livingston) appears to be shaky. He’s the kind of guy who conspicuously offers books to help improve his girlfriend; worse, he’s not a beer drinker—as are Luke and Kate, by vocation and near-constant thirst. The fourth leg of this stool is schoolteacher Jill (Anna Kendrick), a lot more together and mature than her boyfriend Luke. All four head to Chris’ family’s cabin on Lake Michigan—a weekend trip that portends future decades of married life for the two couples unless some bed-hopping interrupts that fate. Because Drinking Buddies was made by mumblecore director Joe Swanberg (Hannah Takes the Stairs, LOL, etc.), who works fast and frequently on tight budgets, I expected the foursome to stay at that lakefront location and work through their cross-couple sexual stirrings.

Perhaps Swanberg rejects that expectation because we’ve all seen the same movies with similar plots; or more damningly, perhaps he simply doesn’t know how to write an ending for his conventional setup. Kisses are stolen, confidences are broken, and the dramatic crux of the piece involves moving a couch. Maybe that’s life for millennials, but moviegoers expect more for their 10 bucks. Swanberg doesn’t seem to direct scenes so much as simply hang out with his cast. Highly conversational but minimally articulate, lacking any story momentum or serious conflict, Drinking Buddies stalls in its own laxity.

Listed as a producer for the film, Wilde would appear to be using Swanberg as a means to escape her Tron-babe image, and this wide-browed beauty isn’t entirely implausible as a fixie-riding marketing gal who trades on her charm just past the point of ethical behavior. Unlike Chris and Jill, Kate isn’t quite an adult. (About Luke, opinions may vary.) If Drinking Buddies is half-baked (or half-brewed?), so is its heroine. Brian Miller

Guitar Innovators: John Fahey & Nels Cline

Runs Fri., Sept. 6–Thurs., Sept. 12 at Grand Illusion. Not rated. 84 minutes.

This program presents two takes on the guitar-hero archetype, though their differences are more about timing than perspective. The first profiles John Fahey (1939–2001), the inventive guitarist and musicologist. The second is told from within the creative crucible of Nels Cline, lead guitarist for Wilco, who’s actively reinventing the instrument for this new century.

Guitar players and enthusiasts are the intended audience for both docs, but this is also a very kind pairing for the casual fan, who can learn where Cline’s racket comes from before being subjected to it. The hour-long doc The Search for Blind Joe Death: The Saga of John Fahey opens with train tracks and rolling countryside before The Who’s Pete Townsend appears, proclaiming Fahey the William S. Burroughs or Charles Bukowski of folk guitar players. It’s a nice bit of framing that creates great expectation for the artist, though his early life isn’t that unique. Talking heads guide us through his artistic development, one music critic suggesting that the babbling brooks of his youthful wilderness hikes inspired Fahey’s rolling, repetitive, slightly discordant finger-picking style. Among his disciples are the Decemberists’ Chris Funk and Calexico’s Joey Burns, who provide humorous, if somewhat removed, accounts of the far-out Fahey.

James Cullingham’s doc then wisely moves on to Fahey’s development as a musicologist. After starting a record label to release his own records (because no one else would dare), Fahey toured the South, knocking on doors in search of old blues standards he could reissue. It’s this curiosity and hunger that make Fahey a compelling character—along with early interview footage that features the young artist ashing cigarettes into his guitar.

Yet shortly before his death, Fahey connected with Sonic Youth’s Thurston Moore to record abstract electric-guitar sound collages. That departure from his folk roots is no less jarring than the second doc of the evening, Steven Okazaki’s half-hour Approximately Nels Cline. The film presents Cline in his studio, experimenting with sound, collaborating with a handful of notable musicians, and sharing his well-examined philosophy on intuitive guitar picking. It’s less comprehensive than Blind Joe Death, but the entertainment value is high.

Do Fahey and Cline have anything in common? Maybe they don’t need to. It’s possible to appreciate both musicians as one-of-a-kind during this double feature. (Note: Seattle guitarist Bill Horist will perform before the Friday- and Saturday-night screenings.) Mark Baumgarten

Off Label

Runs Fri., Sept. 6–Thurs., Sept. 12 at Northwest Film Forum. Not rated. 80 minutes.

Containing little in the way of news or information, this advocacy doc about Big Pharma was supported in part by Northwest Film Forum and screened at last year’s Local Sightings Film Festival. It’s not local, however, nor are any of its half-dozen subjects, all touched by the testing, treatment, and misadministration of psychoactive drugs. (And no, the film has nothing to do with Tom Cruise or Scientology, though that would’ve made it more interesting.) Directors Donal Mosher and Michael Palmieri sympathetically portray the “guinea pig” drug testers who eke out a living, barely, participating in human drug trials. They’re a sad lot, led by one bitter blogger who aged out of the medically desired demo and now inveigles against the industry that once supported him. Or abused him, depending on your perspective.

We also meet a bipolar woman who benefits from her bucketful of monthly meds, despite serious side effects and even more serious bills. An ex-con describes his uninformed consent to a prison drug trial that’s given him chronic health problems. And here’s a likable young Iraq War vet suffering from PTSD. “I don’t need medication. I need help,” he says. This is undoubtedly true, but while Frontline or any serious documentary would explain why drugs are so much cheaper than therapy, then provide numbers and an economic context against our nation’s rising health-care costs, Mosher and Palmieri just skip to the next friendly subject. Here’s a pair of tattooed punks in Rochester, Minnesota, who hate the Mayo Clinic—“It’s where people go to die”—but are funding their wedding by participating in drug trials. How cute.

The only guy worth following here is a former drug rep turned academic and consumer advocate, Michael Oldani, who explains how shady salesmen encourage doctors to write prescriptions for off-label drug uses. But what are the industry’s profits? What are the financial incentives for those doctors? And what do physicians or the FDA or public-health experts think? Again, Mosher and Palmieri don’t think to ask, and can’t even be bothered to read the basic literature (including Ben Goldacre’s Bad Pharma, for a start). Their movie is like a placebo for actual thinking. (Note: The directors will attend Friday and Saturday’s screenings.) Brian Miller

Short Term 12

Opens Fri., Sept. 6 at Seven Gables. Rated R. 96 minutes.

Expanding his prior short film, Destin Cretton’s affecting little indie drama is set in a foster home where troubled young residents age out at 18. Deprived of real parents, they grudgingly look to staff members like Grace and Mason for guidance. One minute they’re docile and grateful for the affectionate rule-givers, the next they’re throwing tantrums or fleeing the campus. (Off the grounds, staffers can only follow the kids and try to talk them back to the facility.) Both in their 20s, Grace (Brie Larson) and Mason (John Gallagher Jr.) are a couple, a fact they try to disguise at work—though it seems an open secret among the kids.

As it lurches from crisis to outburst to revelations of past abuse, there’s a kind of amped-up naturalism to Cretton’s film. Normal kids from loving homes wouldn’t exhibit such behavior, and the whole point of this facility is to shelter damaged teens with no other place to go. So of course they have unhappy stories to share—or conceal, as is the case with 15-year-old Jayden (Kaitlyn Dever), a surly new arrival with much eyeliner and considerable attitude. With her sketchbook and wrist scars, the girl arouses a protective, almost sisterly instinct in Grace, who also projects her own past traumas, gradually revealed, upon Jayden. “I didn’t think about it until I met you,” the counselor tells her charge. Grace is less in command than it seems, and her wavering authority gives the film a certain kinship to Half Nelson.

Ever-decent Mason, the thinnest-drawn character here, is patient and understanding until he’s not. (“You won’t let me in,” he implores Grace.) Several kids have various teary episodes, but the story boils down to Grace’s secret—two of them, actually—and the need for everyone involved to achieve catharsis and healing. But what else would you expect but a therapy movie in such a therapeutic setting?

That the film never loses your goodwill is a credit first to Larson (United States of Tara, Rampart), who convincingly guides Grace from poise to panic, and second to Cretton’s handling of his likable young cast. Cretton (I Am Not a Hipster) isn’t far along in his career, so we can expect his writing to improve. And he gains extra points for the film’s sweet coda. Short Term 12 may not surprise the viewer, but it convinces you of the need for foster care and of the burdens placed upon those who run that overtaxed system. Brian Miller

PSpark: A Burning Man Story

Runs Fri., Sept. 6–Sun., Sept. 8 at SIFF Cinema Uptown. Not rated. 90 minutes.

Believers in the stereotype of Burning Man as merely an E-fueled hippie rave in the northwest Nevada desert will find lots of footage here to confirm it, but that’s not the focus of Steve Brown and Jessie Deeter’s doc, which concentrates as much on the crisis that marred the 2012 gathering—for some, permanently—as on the event itself. Organizers saw it coming: BM’s increasing popularity ensured that eventually demand would outstrip capacity; and, confronted with 80,000 ticket requests and a Bureau of Land Management–mandated attendance cap of 60,000, a lottery system for ticket allotments seemed the only answer. (In 2003, the most recent year I went, attendance was 30,000.)

It was a significant philosophical shakeup: This utopian experiment in radical inclusiveness now had to keep some people out. Longtime Burners, faced with not even being allowed to buy a ticket, were outraged, and the large-scale art installations that for many are the festival’s raison d’

e

tre were threatened: Why start planning and building if you don’t know whether you can go? (The most interesting of the potential attendees profiled here, San Francisco’s Katy Boynton, goes ahead anyway with her work: a 14-foot-high heart made from elaborately bent metal pipes, sort of a wire sculpture writ large.)

Another issue touched on in Spark: the controversial rise of “plug and play” or “turnkey” camps, fully catered experiences in which, basically, you pay to have other people set up everything for you. One not touched on (albeit debated extensively elsewhere): BM’s extreme racial homogeneity, the grandest example of Stuff White People Like. (I don’t recall seeing a single African-American face anywhere in this 90-minute film.) But if all this is starting to sound like an old episode of Firing Line, rest assured that scenes of the 2012 event are plentiful and dazzling, some of the most luscious BM images I’ve ever seen. If, like me, you’ve been away for a while—and still feel an I-should-be-there pang the Saturday night of Labor Day weekend, when the Man burns—Spark will have you aching to return. Gavin Borchert

PTherese

Opens Fri., Sept. 6 at Varsity. Not rated. 110 minutes.

Back in the first dewy shine of Amelie (2001), I would not have anticipated beginning a review with the words “Audrey Tautou is frankly too old to [fill in the blank].” But the years pass. And so: Audrey Tautou is too old to play the early scenes here as a teenage bride in 1920s France. Thankfully, the movie advances in time, and the still-youthful Tautou (she’s 37) very effectively brings her eerie presence to bear on an enigmatic, controlled, supremely rational character. In this adaptation of the 1927 novel Therese Desqueyroux by the subsequently Nobel Prize-winning Francois Mauriac, Therese is very far from an old-fashioned lady of literature. She enters into marriage with the practical and uncharismatic Bernard (Gilles Lellouche); their families own vast swaths of adjoining pine forests, and their union will create a profitable dynasty. Poker-faced Therese seems all right with this, although she becomes troubled by news that Bernard’s sister (Anais Demoustier)—her lifelong bestie—has launched a torrid affair with a callow-yet-hunky young man. This is a prelude to the section that occupies much of the film, as Therese ponders the exact dosage of her husband’s anemia medicine, which contains arsenic. He trusts her to keep track of how much he’s ingested, and she begins to measure her future in spoonfuls of the stuff.

We have to guess at the last part, because although a homicidal impulse enters Therese’s actions, the film does not provide reasons for her behavior. This reticence will make Therese a tough sell—it’s neither a feminist liberation scenario nor a full-blooded murder melodrama—but it’s the finest aspect of the movie, scrupulously executed by veteran director Claude Miller, a onetime assistant to Francois Truffaut. (He directed a lovely Truffaut screenplay, The Little Thief, and died shortly after completing Therese.) A somber mood prevails over this project, as though to remind us that the decisions made by these characters really are a matter of life and death—and maybe all decisions are.

Therese begins as a familiar kind of French costume picture, but its grim undercurrent marks it as something else. I won’t make gigantic claims for it, but I admire its narrow focus and its refusal to play up its leading lady’s charm. It’s unlikely to delight Tautou’s fans, and that speaks well of it. Robert Horton

E

film@seattleweekly.com