If history is the fused composite of past stories, it’s fair to question whose hands were involved in the alchemy. While some understand history as an objective account of what happened, others, who approach historical canons as interpretative, ask “What happened, according to whom?” Interdisciplinary artist Chris E. Vargas believes in the latter approach. As the executive director of the roving Museum of Trans Hirstory and Art (MOTHA), Vargas organized an “imaginary museum” of queer and trans history that both replicates and challenges seemingly neutral historical archives and encyclopedic history exhibitions.

Trans Hirstory in 99 Objects is a multi-exhibition project in its second iteration at the Henry Art Gallery’s free exhibition space Test Site. Featuring both archival materials and works by contemporary artists, the project explores the multifarious histories of “transgender, gender non-binary, and gender-transgressive identities and expressions.” Before the show closes this Sunday, I spoke with Vargas about the challenges of reeling together an archive, constructing a history around identity categories that are constantly evolving, and the queer and trans heroes of the Pacific Northwest.

How did MOTHA come to be?

I’m primarily a film and video artist—that’s been my background up until this project. I’m such a reluctant curator, because MOTHA started out as a conceptual art project. It’s an exhibition project, but because it’s a creative look at history, it’s also an art project in its bigger form.

MOTHA started in 2013 as a broadside poster, a big folding poster that featured around 250 trans artists. I solicited my online network of friends and asked for the names of their gender heroes, people they have looked to in the past for their models of gender expression. I always envisioned this project as a way to reflect on inclusion in a critical way, not just as a celebration, because I don’t necessarily think inclusion in huge institutions is necessarily the pathway to liberation for a lot of people.

99 Objects is modeled after the British Museum’s A History of the World in 100 Objects and the Smithsonian’s History of America in 101 Objects. I chose the number 99 to signal a pre-acknowledgement to the roadblocks to narrating this history that’s been unhistoricized. Trans history is not as straightforward. There’s the difficulty in calling things transgender that predate the term, for example. I wanted to acknowledge the historic and cultural specificity of the term transgender.

Museum of Transgender Hirstory & Art poster. Courtesy of the artist

I’m interested in your comment that institutional inclusion isn’t necessarily the pathway to liberation. How do you see your project as an effort to critique that?

MOTHA embraces a non-comprehensive way of doing history. An example of contested history is the Stonewall riot in New York. There’s a lot of disagreement about how this started. Was it started by gender-nonconforming street youth or by gay bar patrons? Was it Marsha P. Johnson? Was it Sylvia Rivera? What I imagined is that I would open it up to artists to imagine these things connected to these instances and re-create them to fill in the archive. And also create objects that are just expansive, that find the vagueness of history and use that to expansively narrate history in whatever way they imagine.

Can you give me examples of work in the show—more conceptual work vs. more straightforward archival material?

Some of the archival materials comes from the UW special collections. There are images of the Garden of Allah, a cabaret in the Pioneer Square area. There are tons of images of house parties where people are dressed in costumes. That stuff is interesting because it just tells a particular moment of queer, trans, gender-nonconforming history connected to Seattle bar culture of the mid-20th century. There’s also a scapular, which is a nun garment worn by this figure Assunta Femia, who is an early founder of a lot of interesting queer organizations like the Wolf Creek Radical Faerie Sanctuary in rural Oregon and The Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence, that nun drag troupe. She also founded a vigilante street patrol in the Castro in San Francisco called the Butterfly Brigade. She was always wearing a nun’s hat. She was also called “The Nun With the Gun” because she carried a gun for self-protection.

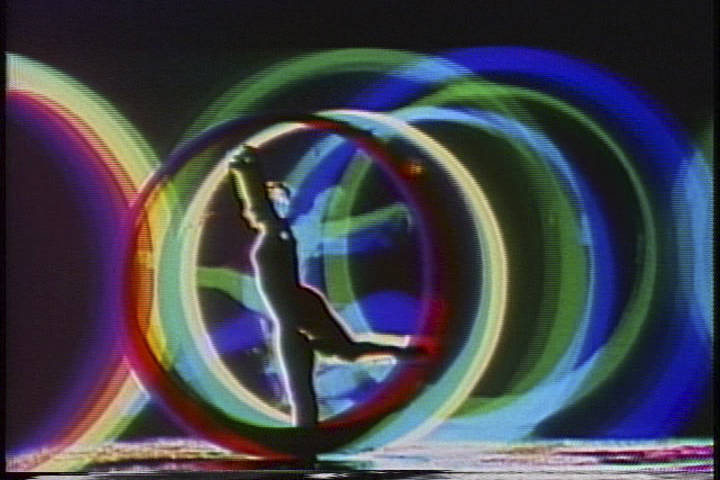

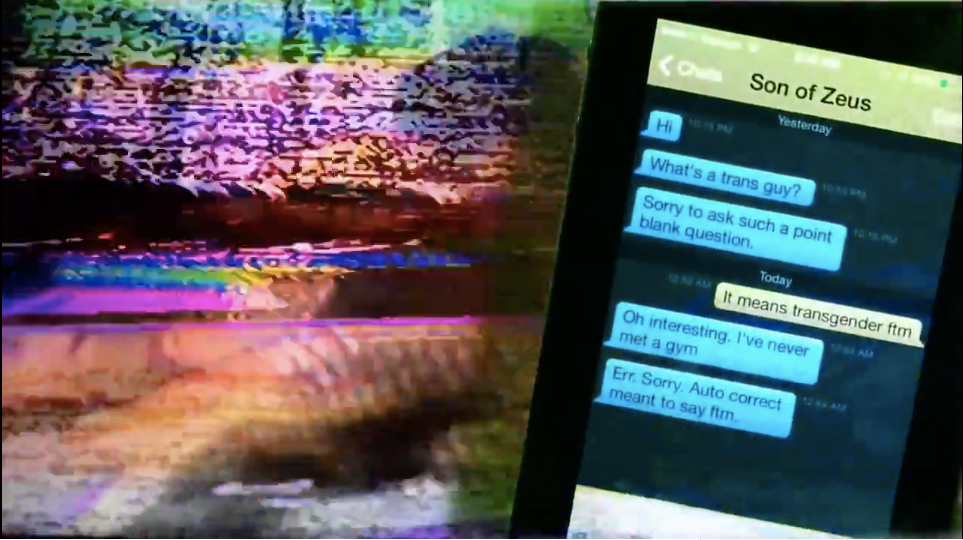

And then there’s a lot of other artwork, like Rhys Ernst’s Dear Lou Sullivan, a video about the late activist Louis Sullivan who was an early female-to-male transexual activist who died of AIDS. Ernst makes a video that draws a line between his experience with this figure as a trans guy. Also Jono Vaughan’s Project 42: She makes garments that memorialize victims of trans violence and murder, such as Brandy Martell, a woman who was murdered in Oakland. Embedded in the dress [are] patterns from Google Earth of the site of the murder. She creates patterns for performances that act as a living memorial. That’s a little more conceptual.

Video still from Rhys Ernst’s “Dear Lou Sullivan”. Courtesy of Visual AIDS

Given that the first show was in L.A., can you tell me about how the current one at the Henry was shaped around the Pacific Northwest?

It was a bit of a history lesson for me in terms of what the colonial history of the area was, the history of the Gold Rush, the Yukon. The Nell Pickerell stuff that I came across was really interesting. [Seattle] was like a West-style town. I made a video slideshow of articles that I found about Pickerell, who was assigned female at birth but dressed in male garb and hung out in male bars and professionally got male jobs, getting in trouble with the law. The media was fascinated. More than anything, these clippings tell the story of historic media fascination with people who transgressed gender norms.

From The day book. (Chicago, Ill.), 27 March 1912. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

It feels like the preservation and the archiving of PNW trans history is a lot less central. When I was doing this at an archive in L.A., there were central hubs for queer and LGBT history, whereas there isn’t a lot of stuff here. So a lot of the stuff I brought into the exhibition were from various collections, some private. The materials for The Transfused, a punk opera that happened in Olympia, is from the people who made it, so that’s not yet living in an archive. A lot less centralized. But in this exhibition I only really started to scratch the surface. This could be a lifelong project.

The PNW is also more white than L.A. Did you see race configure your work of assembling an archive?

More often than not, you’ll find things in institutional archives by mostly white people. The people who have housing security and job security are white people, and when it comes time to preserve or do something with the material of their lives, it’s more ready to be archived. The archive definitely points to social privilege.

So what do you see as the role of historical memory in struggles for liberation? What can people gain from this project?

My experience is that queer generations don’t talk to each other. It’s not like we’re connected through blood family, so there’s not necessarily this interchange between generations. I think it’s so important to talk intergenerationally. Marsha Botzer from the Ingersoll Gender Center has been so involved in the political struggle, for example. To hear narratives of how stuff like this has gone down in the past and using that to struggle better for the future is invaluable. There’s a tendency, and I’m guilty of it, to think that I discovered something new. Looking at archival stuff, I realize there’s so much that repeats. We can learn from how people have struggled and fought beforehand, today.

Trans Hirstory in 99 Objects, Henry Art Gallery, 4100 15th Ave. N.E., henryart.org. Free. 11 a.m.–4 p.m. Tues. & Fri.–Sun., 11 a.m.–9 p.m. Wed. Ends Sun., June 4.

visualarts@seattleweekly.com