In any English-language production of Molière, the elephant in the room is poet Richard Wilbur, the greatest American formalist since Frost, whose stately verse translations of Molière have ruled the stage for 53 years and made him rich. But he has always been out of step with our culture. Refined and upbeat, he’s so radiant that after Sylvia Plath’s Bell Jar year, Plath’s mominvited him over, “to exemplify/The published poet in his happiness/Thus cheering Sylvia, who has wished to die” (as he recalled in verse).

Plath’s unhealthier style was the one for our times: negative, punchy, vulgar rock ‘n’ roll compared to Wilbur’s tasteful harpsichord trills. Yet the theater, a more conservative world than poetry’s, has long gone for Wilbur’s retro Molière. “Molière has had no better American friend than Richard Wilbur,” wrote Frank Rich.

Oh, yeah? How about Constance Congdon? Her slangy adaptation of Molière’s The Imaginary Invalid—a scathing satire of self-deluding losers and the physicians who milk them and kill them—goes for farce, farts, shameless puns, and nihilist pratfalls worlds away from Wilbur’s Molière. In fact, it’s right out of our world, ruled by the borborygm comedy of the Farrelly brothers and Mike Myers’ Fat Bastard with his turtle head poking out. The obscene farce of the U.S. medical insurance system makes the theme timely, too. Director David Schweizer, a big New York star, cranks the crude fun up to 11, to impeccable effect.

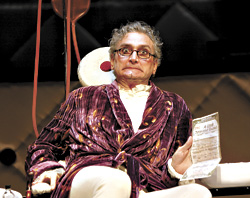

Riccardo Hernandez’s gem of a set adds to the kinetic glee of the evening. The centerpiece is the sick chair where our well but worried hero, Argan (Rocco Sisto), emits phantom ailments and pungent alimentary exhalations that are all too real. His chair has upholstery buttons reminiscent of a whoopee cushion, a look echoed in the three concentric semicircular walls around him. The walls also suggest a madman’s padded cell, and they rotate, along with parts of the stage floor, permitting actors to hop on and off moving surfaces, redeeming the potentially static quality of a talk-intensive play without much physical action.

Sisto, whom you’ve seen in movies and TV shows, is pretty good as the hypochondriac, sniffing his flatulence like a wine snob, puzzling over the odd note of cumin. His soliloquys are only so-so, though. When he’s great, it’s in concert with his sarcastically unservile servant Toinette (smoky-voiced Alice Playten, who’s been a Broadway star since Gypsy) and the other women in his life.

As his second wife, Beline, Julie Briskman outdoes even her legendary past performances (Enchanted April, The Women). With a hairdo recalling Marie Antoinette, or maybe the Bride of Frankenstein, Beline is so bad, her very name triggers comically ominous sound cues (kudos to Matt Starritt). All she wants is Argan actually dead from his non-illnesses, so she can spend his money on her honey, the Notary (Bradford Farwell), and pack Argan’s inconvenient daughter, Angelique, off to a convent.

Everybody’s funny, but nobody more so than Zoe Winters’ Angelique. She’s rouged like a crazed doll, and her ringlets bounce like very tight Slinky toys—in fact, her whole body seems to be mounted on springs. She has absolutely zero control over her emotions (an effect achieved by Winters’ absolute control). When her plan to marry Cleante (the amusing Andrew William Smith), the dim galoot she met at the theater, goes well, she’s all giddy lust; when Argan instructs her to marry a med student so he can get free treatment, she’s a symphony of agonies. It’s a performance as impressive as Isla Fisher’s in Wedding Crashers and Amy Adams’ in Junebug—over the top and on the nose.

Partly, it’s her costume that makes her so funny. Her skirt has a square-dance-ish stiffness that rustles and sticks out when she leaps and gesticulates and flexes her face into masks of tragedy and comedy. Throughout, David Woolard’s costumes are as sumptuous as the ones everybody swooned at in ACT’s The Women, and these clothes also know how to act. The notary’s gratuitiously brass-buttoned, pinstriped suit, crossed with period Molière-wear, greatly enhances the impact of his superb comic turns. Ian Bell is a marvel as De Aria, the demented med student Argan wants Angelique to wed: Raised in a barnyard, he has acquired the quizzical cocked head, strange gait, and clucking excitability of a chicken. But even Bell wouldn’t be as bizarrely hilarious without the hay-strewn outfit in which Woolard fits him out.

This play needs all the help it can get from the Rep’s remarkably talented ensemble. Not even the proliferating subplots Molière added (and Congdon trimmed) could obscure the sketchiness of the protagonist—a part he wrote for himself to play sitting in a chair, because he was mortally ill—and the unpropulsiveness of the thin plot. The ending is almost as puzzlingly abrupt as No Country for Old Men. Even in brilliant hands, it’s no masterpiece. It is, however, a gas.