The exhibit “Freeing the Figure” occupies a small corner room at SAM—it looks like a sideshow compared to the sprawling Calder exhibit nearby. But don’t overlook it. Curated by SAM’s Michael Darling, it includes more than a dozen of some of the most important names in Northwest and international art.

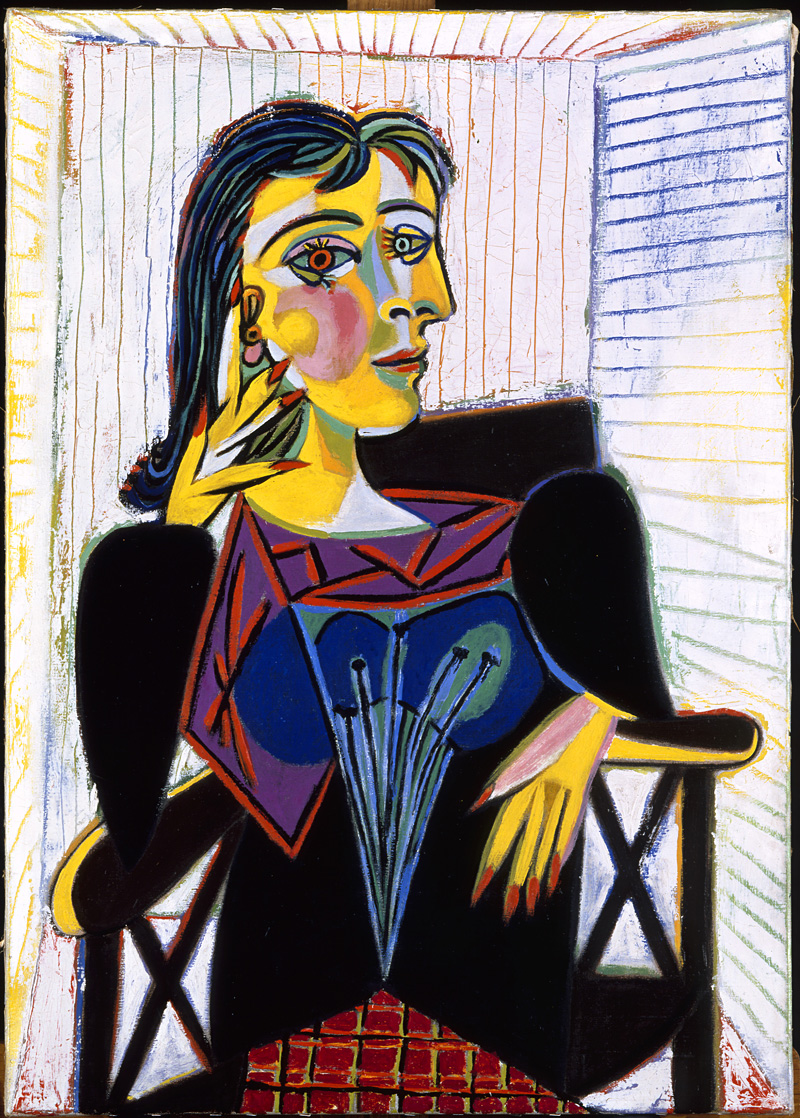

Everything on view demonstrates that after Picasso, artists felt free to abandon literal realism in depicting the figure. You probably won’t find this news astonishing. But the show has a more interesting goal—to free the figures of Seattle great Jacob Lawrence from the way they’re almost always seen: as characters in a narrative about black struggles.

Lawrence’s celebrated 1975 screen print Confrontation at the Bridge, for instance, is about the fateful turning point of the civil rights movement on March 7, 1965, when Martin Luther King’s marchers crossed the Edmund Pettus Bridge to face the foaming jaws of the German shepherds sent by Birmingham, Ala., police chief Bull Connor (who stupidly gave King the telegenic violence he required). Usually you see Lawrence pictures arranged like funny-papers panels—he was influenced by the Katzenjammer Kids. You read these pictures. Lawrence felt so strongly about the unity of his narrative statements that he tried to sell his 1942 The Migration series for $2,000 if somebody would take all 60 pictures. But by surrounding Lawrence with other artists, Darling helps us see the bridge scene outside of history (and its exhibition history), in purely formal terms.

The figures are an interlocked mass of bold primary colors. The marchers’ faces are distortions, recalling African masks and cartoon silhouettes. The figures are design elements with a punctuating percussive quality, the formal equivalent of the emotion he’s trying to convey. The hands are crude, splayed claws gripping the bridge. The stylized whites of their eyes and about-to-be-broken teeth give a sense of abruptness—terror freezes time. Their jagged reflections convey chaos to come; reflections of red dresses echo the dog’s red mouth and suggest a slick of blood on the water. The sky looks like daggers, and like the dog’s fangs. It’s the rhythm of shapes you respond to, not just the familiar story.

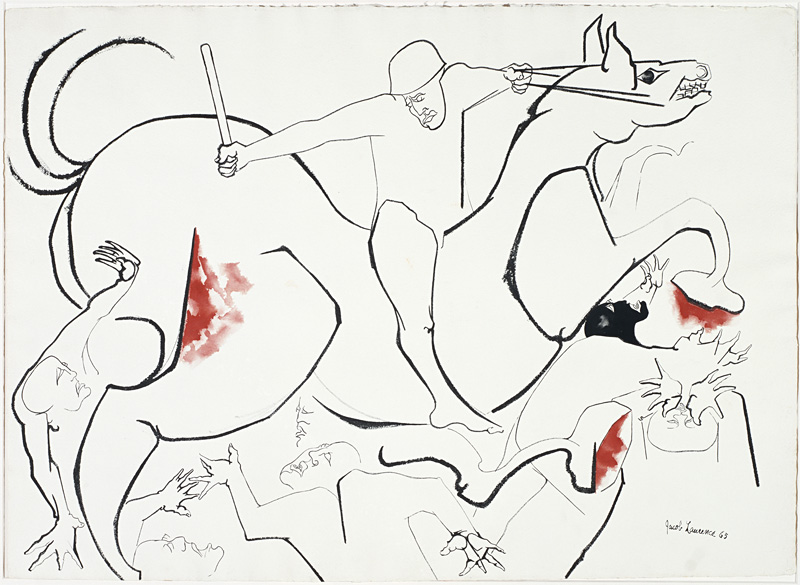

Lawrence’s Struggle #2 (from 1965, pictured)—a virtual pastiche of Picasso’s Guernica—still more freely distorts its helmeted horseman about to billy-club five trampled figures. Some of the anguished hands are like explosions. Instead of incorporating Lawrence’s usual puzzle-like patches of color, this work is all about the simple power of line (like the nearby Calder works).

Darling’s show invites you to compare Lawrence to other famous figure-benders, though without much wall-text guidance. Next to fellow pioneering black artist Romare Bearden, Lawrence looks more illustrative, less otherworldly; both look gently old-fashioned next to the later black barrier-breaker Robert Colescott, who also mines a high art/low art vein. Colescott’s 1969 Night and Day, You Are the One, starring a primitivistic black figure and a faceless, helpless white maiden in a bright nightmare composition of jarring color shifts, is haunting, powerful, in-your-face.

The Mexican José Clemente Orozco’s Mujeres II—1935 is presumably here because he taught Lawrence to keep his socially conscious work spontaneous. (Grateful, Lawrence bought him a bag of cherries.) But most of the work on view has no apparent specific connection to Lawrence. A toothy de Kooning reduces a woman to a few slashes in neon hues. Philip Guston’s tentacular figure sits in a chair—or maybe is the chair, scarily creeping your way.

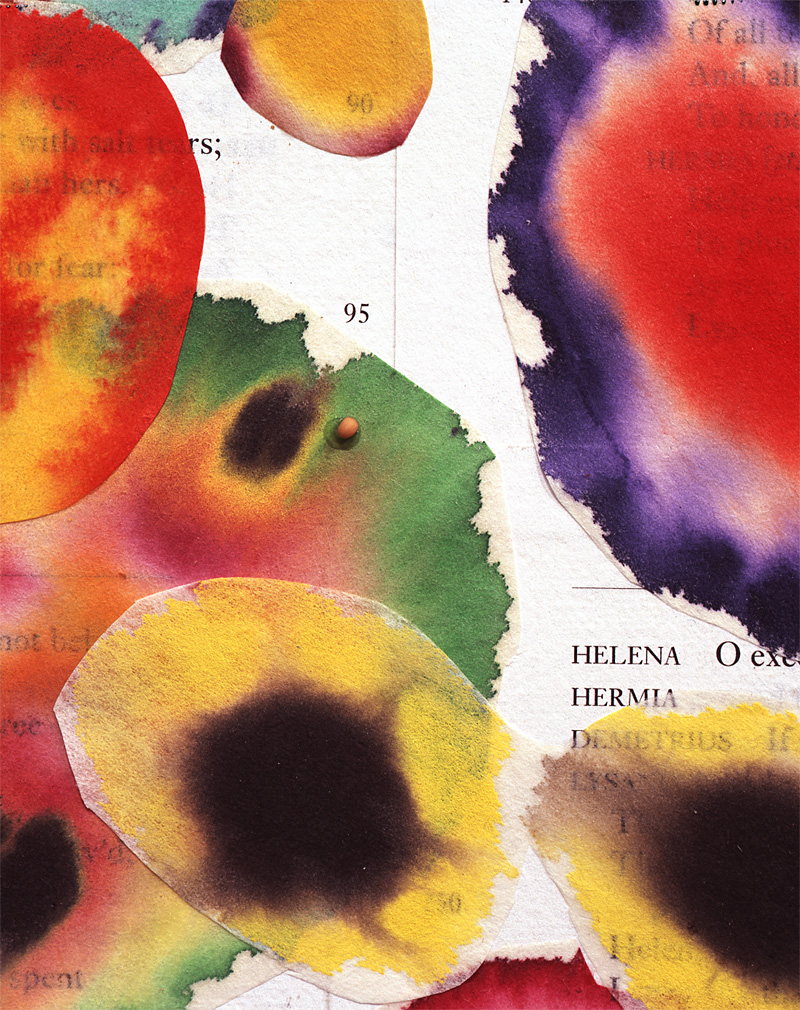

The paintings comment on each other, not just on Lawrence. Near the figures of Seattle’s Fay Jones is esteemed Bay Area figurative artist Joan Brown, whose work often resembles Jones’. Here, Brown uses figure distortion to emphasize massively troweled-on paint. A kid and a toy penguin are hidden in this sculptural canvas, much like the images in Highlights for Children.

The show’s standout is the totemic nude at its center, Untitled Standing Figure No. 5 (1980) by Brown’s husband, Manuel Neri. Faceless, a triangular halo symmetrically echoing her pubic triangle, she stands as high as an Egyptian idol or the hominid Lucy, her feet melting into her base. In front, her rough bronze skin calls attention to its material; in back, she’s more lifelike. There’s more weight on one leg, suggesting movement; sensitively modeled shoulders lead to arms like sticks or paddles, slashed with marks of white patina. Elegant as a hieroglyphic, this figure breaks free of its figurative subject matter to achieve the stature of myth.

“Freeing the Figure” is more an excuse to exhibit important works from SAM’s collection than a fully articulated statement. But how often do you get to see Northwest artists right up against some of the heaviest hitters of modernism?