Like Edgar Allan Poe and Ambrose Bierce, the Rhode Island–born author H.P. Lovecraft created insular fictional worlds ruled by a brutally bizarre and paranoid kind of anti-logic, where lonesome human subjects are driven this way and that by forces—psychological, supernatural, hellish—that leave them swirling like marionettes. For Lovecraft, creator of Necronomicon and the Cthulhu Mythos, these forces are ancient and gothic, ungovernable deities that lie sleeping through the ages until they are arrogantly or accidentally awakened by a curious scientist or ambitious tomb raider. Big, big oops: That’s the typical response to nearly every Lovecraft story, as some creeping, horripilating monstrosity or other is unleashed on a witless humanity.

Geeks and loners and pimply teenage bookworms just love this stuff, in the same way they love hobbits and Philip K. Dick and reruns of Dr. Who and Monty Python; they are attracted to Lovecraft’s self-perpetuating and self-contained mythos, his insider esoterica, and the upheaval and rejection of everyday reality that his gods and monsters represent. The folks at Open Circle Theater are just such geeks. For the past five years or so, right around Halloween, artistic director Ron Sandahl and crew have presented a cycle of three or four of the scariest and most accessible Lovecraft stories adapted for the stage, and their productions have been funny, smart, and wildly entertaining. Using all manner of devices, including puppetry, scrim shadows, and ingenious sound and lighting, Open Circle has gone all out to capture the brooding morality and eerie, archaic atmosphere of Lovecraft’s fiction. The shows have been hilarious and terrifying, often in the same instant. More important, as reified and occultish as Lovecraftian fanship can get, Open Circle has always leavened its shows with a strong jolt of humor, never taking itself or the material too seriously. This, in a sense, is the ultimate tribute to Lovecraft’s cult of the macabre.

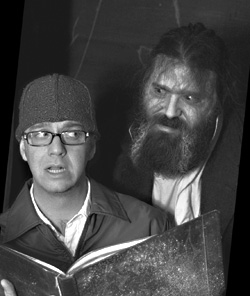

Dreams in the Witch House is this year’s offering, directed by Sandahl and staged at the Rendezvous’ intimate Jewel Box Theater. Once again, three Lovecraft stories are stitched together, this time using the device of a weary traveler (Todd Hull) encountering an “antique and repellent wooden building” on a stormy night. He is compelled by a “creeping curiosity” to enter the seemingly abandoned building; inside, he finds a stack of dusty and, of course, ancient texts, and is surprised by an old man (the always good Aaron Allshouse) who asks the traveler to read to him. And so it begins. The stories that follow are classic Lovecraft fare: In “Nyarlathotep,” an illusionist opens a portal beyond the three visible dimensions, with terrifying results; in “The Cats of Ulthar,” a town learns the gruesome reason for the warning, “No man may kill a cat”; and in the titular story, an academic obsessed with a witch’s escape from a Salem jail in 1692 finds that opening wormholes in the universe can be a bit gut-wrenching—literally.

There is much to enjoy here. The skeleton puppets that appear in “Cats”—including a levitating skull that delivers a tale of woe—are a treat, and the live screened projections in the title story are effectively disturbing. The production also makes good use of the limitations of the Jewel Box’s small space, following the maxim that, when it comes to horror especially, less is more; it’s always scarier to imply what’s behind the door, rather than throwing the door open and letting the monster jump or ooze or pour out.

Compared to years past, however, there is something lacking here. Many of the scenes feel halfhearted or overly goofy. Whereas past productions have succeeded in creating a full and nearly anaerobic environment of Lovecraftian terror, here the cracks show. A big part of the problem is the tone of the show’s humor: The balance is wonky. Some of the cast, in particular Allshouse and John McKenna, achieve an excellent blend of camp and creepiness, but a number of scenes are rendered with too much ham, threatening to push the production into the realm of parody. There is a fine line to walk between comedy, gothic foreboding, and outright gore in any Lovecraft adaptation—think of the genre-defying guts-and-yuks appeal of director Stuart Gordon’s 1985 cult classic, Re-Animator—but Witch House, unfortunately, can’t seem to find its foundation.