“If you’re not part of the straight white world, and you’re slowly seeing [yourself] kind of reflected or shown, any crumb, you think: This crumb is a meal. Because you’ve never had a meal.”

When I first saw that ArtsWest and Intiman had decided to produce Hir, that quote by New York City trans theater artist Becca Blackwell in American Theatre felt like a spark, then a flame, in my gut. The amount of complicated and nuanced theater made by trans people that centers trans voices in the artistic process is very, very small in Seattle theater. Yet as local queer playwright Nelle Tankus says in Deconstruct, “It’s also important to acknowledge that even cisgender heterosexual black/indigenous/people of color are grossly underrepresented in the theater world.” I can only speak for my own experience as a non-binary (genderfucked and transmasculine) white person craving representation onstage that feels authentic and challenging. The Gay City Arts season has been producing a lot of amazing work that amplifies voices of trans people, particularly trans people of color, and it deserves to be recognized and celebrated. There are also numerous queer directors of color inviting trans folks to the creative process. But beyond that, the Seattle theater scene at large has been failing to include trans voices. Where is the radical theater that challenges the steel boot of transphobia as it intersects with white supremacy, patriarchy, capitalism, and beyond? Hir experiments with those crucial and nourishing ideas in innovative and imperfect ways.

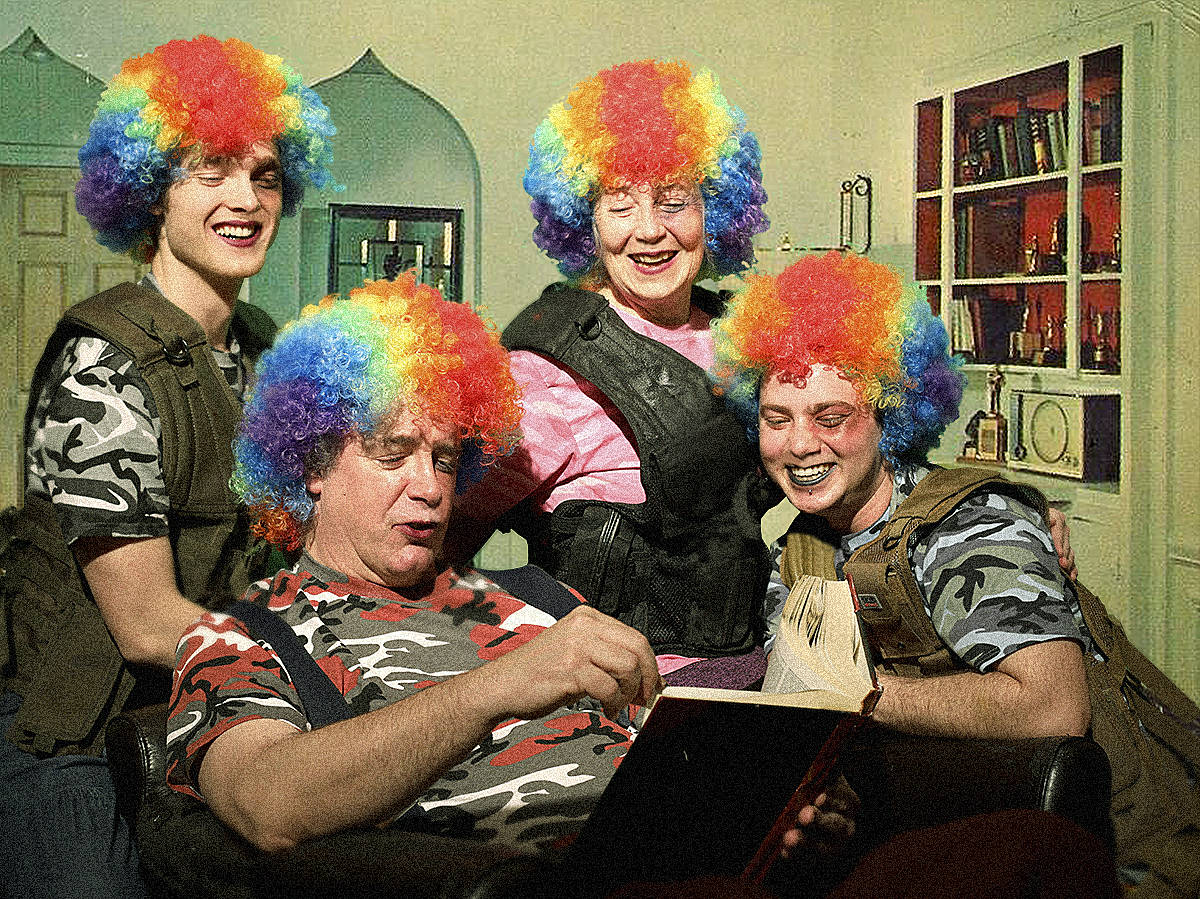

Written by acclaimed creator and performer Taylor Mac, Hir (pronounced “here”) follows the story of a crumbling family. We meet Paige, a mother finding her own freedom and rhythm as a survivor of abuse while exploring the framework of queer liberation with her son, Max, a trans masculine teen in the midst of transition. Max desires the approval of brother Isaac, a returning dishonorably discharged veteran, who’s attempting to restore the home’s culture of masculinity which Arnold, the abusive patriarch, has left in shambles after a life-altering stroke. Hir exposes the failure of oppressive frameworks such as “the nuclear family… [and] toxic masculinity… it is about the deep wound [these frameworks] create and about how these wounds don’t magically go away,” says Hatlo, Hir’s genderqueer assistant director. “We still have to exorcise our demons. We still have to do the healing work and visioning work to build new futures.”

A big part of that work is deconstructing the whiteness in the play. “If you are going to put a bunch of white people onstage, then it has to be hella fucking transgressive and uncomfortable for everyone,” says Hatlo. Through painful and violent interactions between family members trying to live out the impossible American Dream, the intoxicating power of white supremacy and how it affects the white American conscience is unfurled. “It’s all in breakdown, it’s all in chaos,” says Eddie DeHais, Hir’s lead dramaturg.

DeHais is a non-binary Seattle-based theater-maker, artist, and activist. Recently, they have been working on creating equity for trans and gender-nonconforming (TGNC) artists and for performers who have disabilities in the Seattle theater scene. Theaters often only attempt to do outreach to TGNC communities when there’s a highly specific role in a show, gestures that can ring of tokenism and naïveté. According to DeHais, “People don’t know how to be inclusive to TGNC artists. How do we change the narrative for TGNC artists?”

The production has its own cultural advisory committee dedicated to maintaining the integrity of the story. It includes a person who served six tours in Afghanistan, transmasculine folks who know the experience of transitioning, and experts on the effects of a stroke. There will be engaging dramaturgy in the lobby after performances, and resources for audience members to connect with to catalyze conversation and activity beyond the stage.

The team behind Hir wants to disrupt a pattern of passive engagement with storytelling. This is not a show in which “good-hearted white liberals can walk away, patting themselves on the back and feeling good that they saw an issue play,” says Hatlo. Yet I am not sure that this show decenters whiteness. Taylor Mac asked while writing the show, “What responsibility do we have to something that has been abusive to us?” As a white writer, judy’s (Taylor Mac uses “judy” as a prounoun) response to white supremacy is rooted in judy’s own experience. What would it mean for ArtsWest and Intiman to produce a show written by a trans playwright of color? Even better, what if the institutional makeup of regional theater shifted away from white leadership? I ask these questions because transphobia is deeply rooted in a relationship to white supremacy. We cannot talk about one without the other.

When I first read this play, I labeled it as a “trans play,” lacking the deep analysis that Hatlo and DeHais provided for me around the complexities within the plot. Timothy White Eagle, close friends with Taylor Mac and another collaborator in the Hir creative team, says that the show so often gets labeled as trans; though it does engage queer and trans narratives, it is much, much more than that. This play is about the “sunset of masculinity,” says Hatlo. The toxic, patriarchal, white masculinity that is lethal and historical. Adds DeHais, “The idea that you have to make history be kind to white men is over. We are turning a new leaf.”

Hir, Feb. 28–March 25, ArtsWest