President Theodore Roosevelt wrote once that when he heard of the “destruction of a species,” he “felt just as if all of the works of some great writer had perished.”

Though he was not the first person to feel such despair, few people resolved more fervently than Roosevelt to do something about it. Both a naturalist and politician, Roosevelt recognized with rare insight then what is obvious today—that preservation of wilderness in the industrial age would not come by itself. It would require active management—just as much as does a factory or a logging camp or a ranch.

In his term and a half as president, T.R. introduced big-C Conservation into the political narrative with audacious steps to protect a fraction of the pristine land that remained in the United States through the creation of the National Forest Service and a series of wildlife refuges.

The 19th reserve he created was the Lake Malheur Reservation in eastern Oregon. The reservation encompassed land around three lakes—all of which had previously been made available to homesteaders but none of which had been claimed. It was to be a “preserve and breeding ground for native birds,” specifically white egrets. It was officially created on August 18, 1908.

The Lake Malheur Reservation is now called the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge, and has grown to encompass 187,757 acres of vital wetlands. It may support as much as 66 percent of migrating birds in the Pacific Flyway, a swath of land of incalculable ecological value. Fifty-eight species of mammals make their home there, as do 12 native species of fish.

Malheur is the perfect backdrop, then, to reveal the small band of anti-government wackos who are now occupying the refuge as the nihilists they are.

Central to this siege by 15 or so men with guns and cowboy hats is a fundamental contempt for the ecological principles and law borne of Roosevelt’s generation and fostered by generations to follow. Trouble began around the refuge in the 1990s when a local ranching family, the Hammonds, started getting in trouble with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service for running their cattle on the refuge outside the dates allowed by a special permit. The family’s blatant disregard for the very idea of a refuge has made them poster children for a segment of the Western population that argues we’d all be better off if everyone could stick their cows wherever they damn well pleased. More recently, two Hammond men have served jail time for starting fires that burned thousands of acres of public land, one of which may have been set to cover up a large-scale poaching operation; the extension of their sentences was what has brought about the most recent protests.

Legitimate arguments may be made that the government has pursued the Hammonds too aggressively, but that shouldn’t cloud what this standoff (done without the permission or participation of the Hammond family) is about: the absurd—and absurdly popular—belief that land like the Malheur Wildlife Refuge should be handed over to local governments and pressed into economic production.

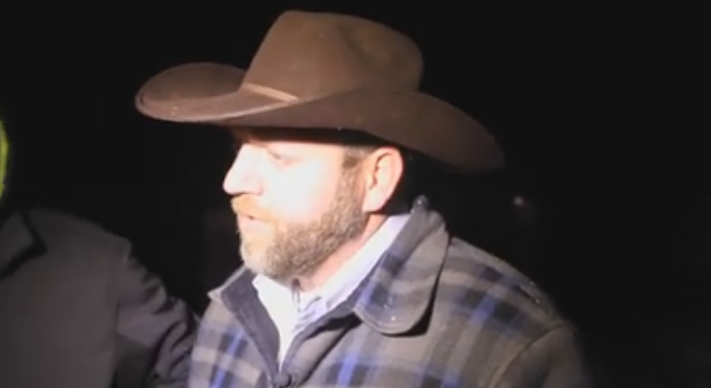

Through environmental regulations, siege leader (and Nevada resident) Ammon Bundy insists, the federal government has made it so people can’t work the land. When people can’t work the land, they become dependent on the government. In this view of the world, seen through the scope of an AR15, something like a wildlife refuge is but a pretense for the government to socially engineer more power for itself. The Bundy gang will only be satisfied, its leader says, when people “can use these lands as free men”—that is, run cattle without giving two shits about species preservation, public access to wildlands, clean air, or clean water.

Thankfully we have a century of evidence

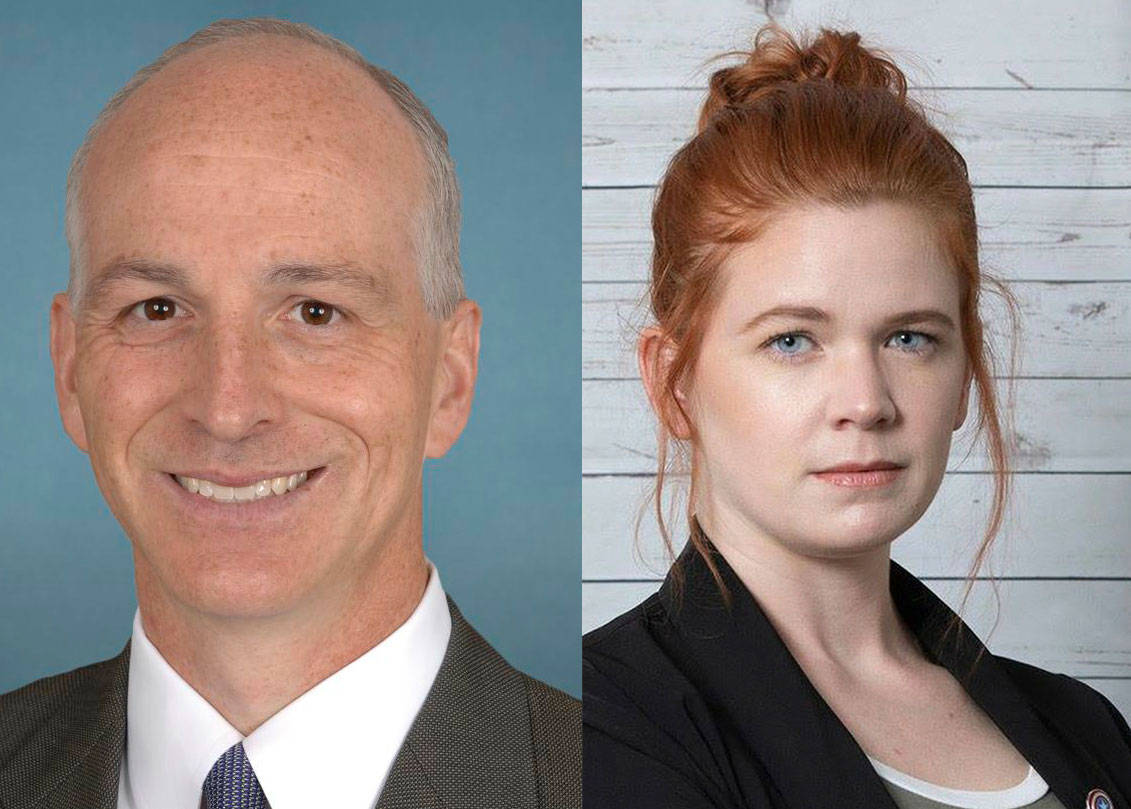

to prove what kind of cow product Bundy is trying to sell us. As Daniel Person discusses in this week’s cover story, an enormous amount of natural wonder was lost in the Pacific Northwest over the course of the 20th century, despite the fledgling environmental movement the century brought on. In Washington, 10 mammals were either entirely removed from the landscape or so diminished that they were no longer considered a viable population. Within our borders, Roosevelt’s writer had lost his work.

Yet the arc of history may be bending toward conservation yet. Thanks to the kinds of land protections and science-based environmental legislation that the Bundys abhor, many of the species lost in our region are now making comebacks. Wolves, antelope, wolverines, and fishers all live again among us, as they had for millennia before European expansion.

It’s a brilliant affirmation that nature will survive if we allow and encourage it to. And it’s a perfect illustration of how vapid the Oregon occupation’s argument against federal land stewardship is. As Dave Werntz, science and conservation director at Conservation Northwest, told Person: “We’ve made good decisions in how we manage the habitat. . . . This is sort of a natural outcome of that.”

He said this before any would-be cowboys showed up at Malheur National Wildlife Refuge. But it will be just as true after they pack up and drive back to Nevada.

editorial@seattleweekly.com