Growing pot commercially and indoors is a delicate balancing act. The quality of the harvest depends on a grower’s ability to get just the right heat, the perfect amount of light, and the exact humidity. The right combination results in the highest-quality pot being grown in the most cost-efficient way. Too much or too little of any one of those elements, on the other hand, can mean lower-quality pot that costs more.

All that balancing takes lots and lots of electricity. And with Washington’s recreational marijuana industry in full blossom, the power drain has become noticeable to both growers and those overseeing the Northwest electric grid.

When marijuana was illegal, power concerns were virtually nonexistent. But now, figures are being collected and crunched publicly—with everyone trying to figure out what they really mean.

The Northwest Power and Conservation Council—which supervises power issues in Washington, Oregon, Idaho, and Montana—estimates that between 0.75 percent and 0.96 percent of the electricity used in Washington goes to marijuana operations.

Right now, 0.3 percent of Seattle’s electricity is going to growing marijuana, according to Seattle City Light. If all the permitted marijuana producers in Seattle were at full production, 0.5 percent of the power would go to pot operations, according to the Seattle utility. (Puget Sound Energy does not have a similar breakdown calculated for the pot industry.)

“The impact of such an energy-intense industry is significant,” read a 2016 story in EQ Research, which estimated the industry’s power costs at $6 billion, nationwide. “These high utility bills contribute to the large operating costs needed to cultivate marijuana.”

All this translates to almost 100 megawatts of energy expended each year for marijuana grow operations in Washington. When you add in Oregon, another state where it is legal to grow recreational cannabis, the estimate grows to 200 megawatts. By comparison, a super-hot summer or an extra-cold winter adds 600 megawatts to the Northwest’s overall power load, said Massoud Jourabchi, an analyst for the Northwest Power and Conservation Council.

That may sound like a lot, but impact of that drain on the power grid is in something of a gray area—it’s large enough for some experts and activists to call for measures to conserve electricity, and small enough that government officials are not considering major Northwest-wide overhauls, but unknown enough to require more study, Jourabchi said. Among those unknowns is the amount of power that was used by marijuana growers prior to recreational pot becoming legal in 2012.

Since legalization, Washington has issued permits for more than 8 million square feet of marijuana grow operations, said Brian Smith, spokesman for the state Liquor and Cannabis Board. That total square footage is broken into four kind of businesses: 540 indoor-only operations, 225 outdoors-only farms, 147 greenhouse-oriented nurseries, and 278 combination indoors-outdoors businesses.

While a breakdown is not available, it is reasonable to conclude that the indoor-only operations are carrying a great deal of the overall electrical load. Soulshine belongs to this group and is one of the state’s grow ops fighting against those monster utility bills.

A medium-sized indoor marijuana growing business operating out of a nondescript warehouse in Renton, Soulshine has no outside signs of what is indoors. No one would really know this is a pot operation until entering a grow room of green plants bathed in warm yellow light.

Soulshine can harvest several marijuana crops a year, as opposed to outdoor farms, which harvest once annually. And like other indoors ventures, the business has better control over its heat, light, and humidity.

Soulshine farms marijuana in six “grow rooms”—soon to expand to nine. Each grow room is a 700- to 900-square-foot chamber—some with double-decker metal shelves and some with single-deck metal shelves. The initial growing takes place in some “vegetation” rooms before the plants are shifted to “flowering” rooms. The heat and humidity remain roughly the same in the flowering room, but more intense lights are needed to nurture the buds containing THC, the biochemical in the plant that provides a high.

Traditionally, indoor growers have used high-pressure-sodium lights or metal halide lights in the 1,000 watt range. Considering that a single grow room at Soulshine might hold 108 lamps that run 18 to 24 hours a day, that is a lot of energy being burned (and that is before factoring in the constant use of power-sucking air conditioners to balance the temperature).

But like many other grow operations, Soulshine has lessened its energy footprint by using light-emitting diodes—less intense lights that consume less energy. There are additional benefits to using these kind of lights. They can be aimed more precisely at leaves and flowers than high-pressure-sodium lamps, and manufacturers are constantly improving them, making them cheaper and more power-efficient.

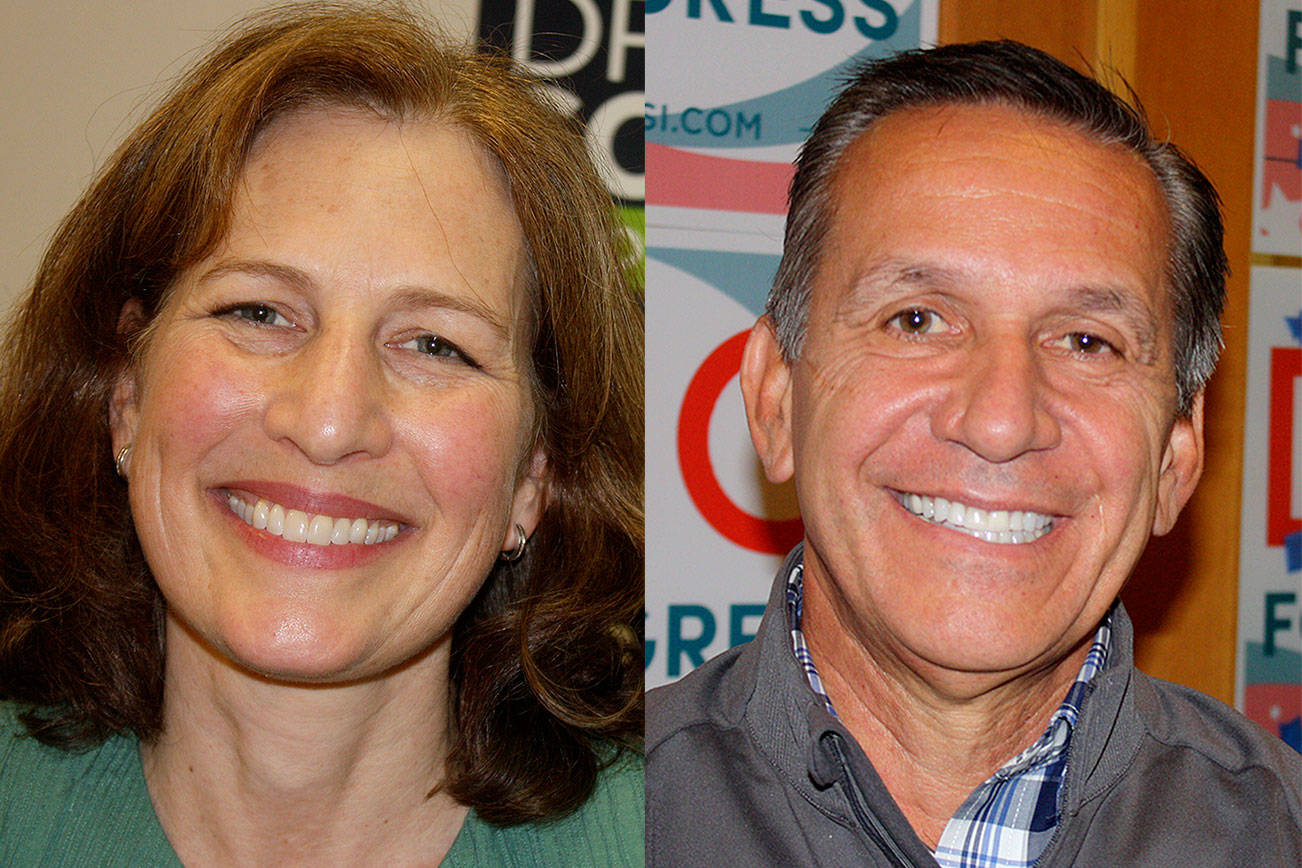

But there is a trade-off. High-press-sodium lamps emit infrared light, which speeds up growth and development of marijuana plants. LED’s don’t emit infrared. Consequently, while Soulshine has been switching to LEDs, it expects to keep some high-power-sodium lights in an attempt to find an optimal combination of both to save electricity while growing at the most-efficient rates, said Patrick Walznak, co-owner of Soulshine. “It’s a balancing act,” he said.

Soulshine constantly tweaks its electrical loads and equipment, trying to trim its power use. Walznak says the operation has cut 30 percent since early 2016. “We’re cutting out amps everywhere we possibly can,” Walznak said.

Walznak said that about 8.5 percent of Soulshine expenses are for electricity in the grow rooms, ading that the majority of indoor marijuana grow operations spend 15 percent to 25 percent of their expenses on power.

There is financial incentive, then, to making the switch. Walznak says there are other drivers as well, noting that the type of business people who grow pot tend to lean politically toward environmentalism and embrace conservation.

Some who want to make the switch are getting help from PSE and Seattle City Light, both of which offer help to marijuana growing operations looking for ways to trim their use of electricity. But these programs tend to be officially geared toward generic agricultural businesses because pot is still illegal on the federal level. Consequently, federal money going to utilities cannot be earmarked specifically for conservation in marijuana operations.

Meanwhile, utilities and the Northwest power council continue to research the issue.

This research will set baselines to measure states’ progress in finding more energy-efficient ways to serve marijuana operations in the same way that utilities seek energy savings for other businesses. “It’s something we do with any other (electrical) loads (from other types of industries),” Jourabchi said.

news@seattleweekly.com