When Cassie Chinn, deputy executive director of the Wing Luke Museum of the Asian Pacific American Experience, stares out her International District office window, she is often greeted with the familiar sight of a crane across the street. “There’s a lot of things happening in our neighborhood and a lot of development slated to happen by developers who don’t have a long history here in our neighborhood,” Chinn said over the phone on Monday.

As an advocate and facilitator of community-led projects in the Chinatown-International District for more than 20 years, she has a clear view of the development and displacement going on in the area and believes that affordable housing alone won’t solve it. So last year Chinn joined the Equitable Development Initiative interim advisory board to help mitigate cultural displacement by looking beyond housing and focusing on community-initiated development projects. Created in 2016 by the City’s Office of Planning and Community Development, the Equitable Development Initiative seeks to spur cultural anchors like the Wing Luke Museum. The initiative is already planning five projects including community and economic opportunity centers in areas in the Chinatown-International District, the Central District and South Seattle where residents and businesses are at risk of displacement.

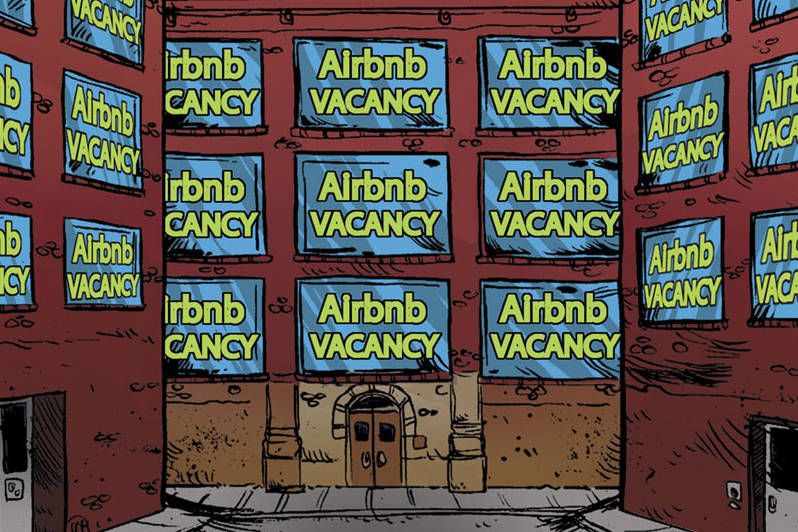

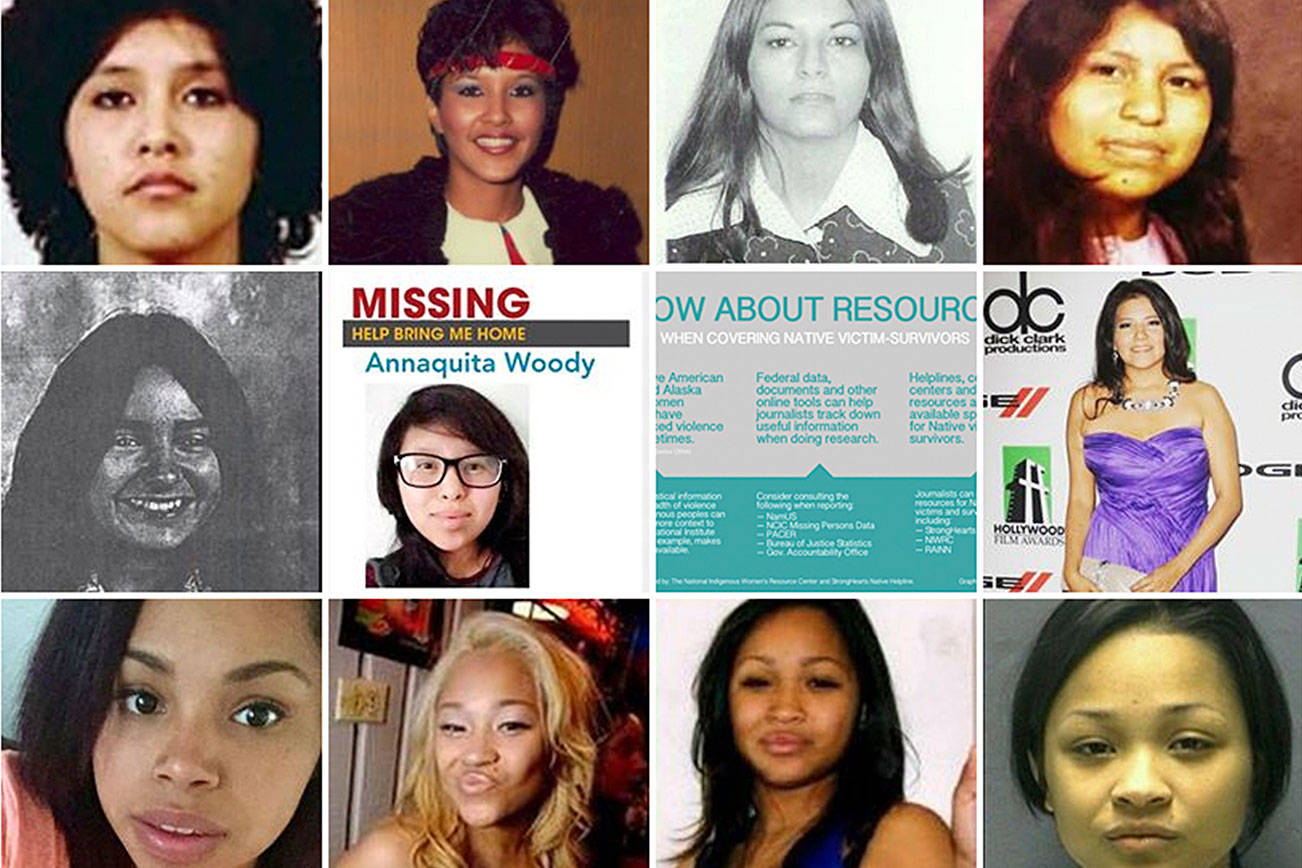

But Chinn is also concerned about another, less visible pressure on the local communities in the International District: Airbnb. She worries that people of color seeking long-term housing in areas like Chinatown, the Central District, and South Seattle that have cheaper rents will lose rooms to short-term rental operators like Airbnb and VRBO. There is reason for her concerns.

Nonprofit Puget Sound Sage recently gathered data from AirDNA, an online subscription source for Airbnb data, and found that short-term rental listings in Seattle increased by more than 2,000 units between April 2016 and August 2017, representing a nearly 63 percent annual growth rate. And according to the group’s 2016 report, more than 1500 long-term units could be converted to short-term rentals by 2019 if growth continues at its current rate. Moreover, there are currently no regulations on short-term rentals in Seattle, although the city has a higher per capita number of such listings than many other cities in the nation, the 2016 study adds.

On Monday, the City Council made an attempt to alleviate some of the strain that these short-term rentals are likely putting on the rental market by voting to tax the operators.

The legislation had been in the works since 2016 when then-Councilmember Tim Burgess proposed regulations that would require hosts to have a special short-term rental license and restrict them to only rent out two dwelling units. The City Council first considered regulations in June 2016, but the proposal was held up in committee following pushback from Airbnb and local hosts who formed the group the Seattle Short Term Rental Alliance. An initial proposal that was finally released in mid-September by the City’s Affordable Housing, Neighborhoods and Finance Committee included a $10 nightly tax on hosts. The legislation again remained at a standstill after Burgess took office as mayor shortly thereafter.

On Monday, the City Council did not approve the regulations, the current iteration of which would exempt short-term rental operators with multiple units in Downtown, Uptown, and South Lake Union. Instead the council accepted Councilmember Rob Johnson’s motion to send the regulatory portion of the legislation back to the Planning, Land Use, and Zoning Committee to be examined more closely. Councilmember Johnson said that he expects the regulatory legislation to return to the full City Council for a vote in mid-December.

But the Council did pass the taxation portion of the legislation at the urging of the packed crowd, adopting Councilmember Mike O’Brien’s amendment that would impose a $14 tax on entire units and $8 per room in a 5-4 vote. If signed by the mayor, an ordinance will go into effect on January 1, 2019.

Where will that money go? Much of it will be invested in the Equitable Development Initiative to fund community-led projects throughout the city beginning in 2019. Last year, the City announced a $16 million fund to get EDI off the ground, yet it has lacked a permanent source of funding until now. Through revenue from the tax, the initiative will receive $5 million a year out of the estimated $7 million generated. The remainder of the revenue from the new tax will go toward administrative costs of regulating short-term rentals, paying off bonds for affordable housing, and funding community-initiated development projects.

Abesha Shiferaw, a member of the Initiative’s interim advisory board and program director at Rainier Valley Corps, a nonprofit that develops leaders of color, agrees that the revenue should go toward anti-displacement efforts. Born in Ethiopia and raised in Columbia City, Shiferaw says that many of her friends have moved out of the area to Kent or Burien because they can no longer afford rent within the city.

Whenever Shiferaw looks at the Airbnb or VRBO listings in her area, she will see a new mother-in-law suite or a room in a house that long-term residents seeking housing could rent, but that instead goes to tourists. She believes that one solution to counteract displacement could be the community-initiated projects. “More money needs to be allocated towards communities of color and community-controlled development, because that’s the only thing that’s going to offset the powers of developers,” Shiferaw concluded.

mhellmann@seattleweekly.com

■