Standing in the Belltown Labor Temple in early June at a mayoral candidate forum, Seattle City Council member Jan Drago used the “c” word. The incumbent’s style, said Drago, didn’t fit with Seattle. It was “the Chicago way.”

The “Chicago” epithet has been dogging Mayor Greg Nickels almost since the day he took office. P-I columnist Joel Connelly started calling Nickels “Hizzoner“—a nickname associated with longtime Windy City mayor Richard J. Daley—during Nickels’ first year as mayor, and continues to deploy the moniker regularly. In a 2007 piece on Crosscut.com, columnist Knute Berger described Nickels as a “strongman, Chicago-born” mayor—even though Nickels’ family left the city of broad shoulders before the future mayor could walk. Seattle Weekly, too, has employed the term: A 2006 story claimed Nickels had “belied his big-softy reputation by instituting a regime of Chicago-style hardball politics that has left a timid city council cowed.”

The idea of Nickels as a Daley wannabe is one of those ideas that has filtered down from the rhetoric of political insiders into general popular perception, even conventional wisdom. At Drago’s campaign launch in front of the Seattle Art Museum in May, David Schraer, a commercial architect active in political issues, said he isn’t supporting the incumbent because “Mayor Nickels is bringing machine politics to Seattle, he’s really trying to make it like Chicago.”

Pressed for an explanation, Schraer said there’s a perception in his field that if you want to get city work, you have to support the mayor. He doesn’t have any specific examples, but he says that’s the reason people he knows are avoiding endorsing anyone else.

As Schraer’s comment demonstrates, Nickels’ challengers may not be doing themselves any favors by painting the mayor as a vengeful Chicago-style tyrant. The scare tactics may be scaring off their own potential supporters.

Nonetheless they continue to make the mayor’s purported political style a campaign issue. Drago has repeatedly said she would work more collaboratively than Nickels—both with Olympia and the city council. Joe Mallahan sent out a press release in June saying: “People in Seattle deserve better than the bully in office now.” And former city council member Peter Steinbrueck—who isn’t running, but who weighs in on the race so often it kind of feels as though he is—one-upped everybody by calling Nickels’ tactics “Gestapo-like” at a breakfast meeting with the Seattle Neighborhood Coalition last month.

Trouble is, it’s almost impossible to get any of Nickels’ accusers to provide details about the mayor’s supposedly Daleyesque behavior.

For instance, in a campaign kickoff speech outside KeyArena on June 4, candidate James Donaldson accused Nickels of strong-arming constituents. “Our citizens and business owners have been politically threatened by people connected with the leadership of our city,” he declared. “And they have been threatened with unfair regulation, inspection, denial of permits and grants.”

But when asked by the Weekly for examples of these abuses of power, Donaldson’s spokesperson Cindi Laws was unable to provide any, saying the individuals involved wouldn’t speak to a reporter, even off the record.

The very word “Chicago” represents everything that good-government Seattleites abhor: high-pressure horse-trading, pay-for-play lobbying, and the unabashed wielding of decision-making power—possibly without first conducting six months of public outreach to stakeholders at local community centers. It’s the ultimate insult in Seattle politics.

After all, scandals have followed nearly every Chicago or Chicago-bred politician for the past century. A close advisor to current mayor Richard M. Daley was sent to jail two years ago for doling out city jobs in exchange for political support, and a Daley family member recently pleaded guilty to taking more than $5,000 in bribes to steer government work to favored trucking companies. More recently, Governor Rod Blagojevich (who built his career in Chicago and keeps a home there) was caught on wiretap responding to the notion that he appoint an ally of Barack Obama to the president-elect’s vacated Senate seat, but without receiving anything lucrative in return: “Fuck him. For nothing? Fuck him.”

Sitting for an interview with Seattle Weekly in the the Columbia Tower’s food court, with only his campaign spokesperson and a baggie of cherries (which he offers to share), Seattle mayor Greg Nickels hardly seems cut from the same cloth. This is the man whose first TV campaign ad of the year, released last week, opens with what amounts to an apology: “As mayor I’ve made my share of mistakes.”

“I don’t think I would last a week in Chicago politics,” he says. And he calls the accusation that he would withhold building permits or unnecessarily inspect someone’s business as retribution for supporting an opponent in this election absurd. “I have never operated that way and I never will,” he says.

So is Greg Nickels really a Chicago-style bully? Let’s examine the evidence.

You’re Fired

Nickels started his term in office in 2002 by asking all senior staff for letters of resignation. Then he asked them to write a job description, explaining what they do and how it fit in with his agenda. “That was a shock right there,” says former Department of Neighborhoods head Jim Diers.

Diers had served in the job 14 years. He was hired by mayor Charles Royer in 1988 and retained by the next two mayors, Norm Rice and Paul Schell. He became known for trying to let neighborhoods set the tone and direction of the city. He even wrote a book on the subject, called Neighbor Power: Building Community the Seattle Way. At City Hall, he says, he saw his role as being an advocate to the mayor’s office on behalf of neighborhoods when they wanted a new library or opposed new density requirements.

When Nickels took office, the city, as now, faced a budget crisis—worse than the current one, according to Deputy Mayor Tim Ceis. (After SW‘s initial interview with Nickels for this story, all follow-up questions were referred to Ceis.) Nickels proposed cutting a program that gave city money to neighborhoods for improvement projects, such as rebuilding playgrounds. Diers says he vehemently opposed the cuts. The program survived, but with a smaller budget.

It wasn’t long before Nickels called Diers into his office. Diers hadn’t turned in his written statement yet, so he brought it along. But Nickels had already made a decision. “His first words were ‘I’m sorry, but we need a new direction for the Department,'” Diers remembers. He says he wasn’t given any more specific reason for his termination, but he believes Nickels wanted someone who would promote the administration’s policies to the neighborhoods, not the reverse.

Ultimately, Nickels canned about half the department heads shortly after taking office. It was the beginning of Nickels’ reputation as a political bully, but the mayor says it was always the plan to start with a new team. He points out that when President Obama took over in Washington, he kept only one cabinet member—Defense Secretary Robert Gates. “I think you need to make a change,” he says.

Not everyone let go when Nickels came into office sees it as a bullying move. Denna Cline lost her job at the top of the strategic planning office; she says she went willingly and even donated to Nickels’ 2005 re-election run. “A director is a position appointed by somebody, and when you’re a new mayor, you want the person who is going to represent your policies,” she says.

Politically motivated hiring and firing in Chicago is so widespread that it has spawned an ongoing 40-year lawsuit. In 1969, a man named Michael L. Shakman sued the Cook County Democratic Party. He alleged that the political establishment was able to stay in power by threatening to fire any of the thousands of government employees who didn’t support the party’s preferred candidates. A court sided with him, and over the years various settlements with additional plaintiffs have been reached. Still, the practice has continued unabated: In 2005, a federal judge appointed Chicago attorney Noelle Brennan to be the Shakman Monitor. Brennan’s job is simply to collect allegations of abuse and report them to the court. According to her most recent report, dated March of this year, city employees not only continue to be fired for political reasons, but city officials have threatened to fire other employees for cooperating with her.

The Hostility

Liz Rankin worked for the city for 21 years. For the last six, she was a spokesperson for the Director of the Department of Transportation. (She worked most recently for the now-embattled Grace Crunican.) But in 2005 she left. “I loved my job up until this administration came,” she says.

Rankin says that almost everything she said or wrote in her position with the department first had to run through the mayor’s office. Direct interaction with members of the city council was also discouraged; Nickels wanted everything to go through his staff. That kind of micromanagement style suppressed creativity and led to unnecessarily cumbersome days, she says.

She remembers one incident when she spent the better part of a day firing e-mails back and forth with the mayor’s staff on the text for a brochure with new street-use regulations. At one point a member of Nickels’ staff called and yelled at her over the whole situation. Finally, well after 7 p.m. on a Friday, she received final approval on the text as she’d originally written it. Rankin says she told her supervisor that if she went through something like that again, she would file a grievance.

On vacation one day in Hawaii in 2005, Rankin says, she realized she didn’t have to keep feeling so miserable. She was eligible for retirement, so she quit. “When I left, I was so happy to be out of there,” she says. “It had been so negative.” Her husband, Gerry Willhelm, the city traffic engineer, was also let go after Nickels came on board. She says he had three job offers waiting for him, and he now works as a project manager for transportation consulting firm H.W. Lochner.

Donna James was hired by Charles Royer in 1984 to work on projects to encourage families to stay in the city limits. In the ’90s, she took over the fledgling film office, working to connect the city to local and national film and music projects. She’s quick to note that not all mayors are sweetness and light. She once got into a shouting match with Norm Rice (known by the nickname Mayor Nice) over the notorious “teen dance ordinance” that imposed onerous restrictions on all-ages events. James thought it went too far and wanted Rice to repeal it. James lost the fight, and the ordinance stayed in effect until 2002. But she says she at least felt the mayor listened to her concerns and tried to take them into account.

Later, when James worked for Paul Schell, she says, he constantly asked questions about what she thought the city’s role should be in supporting film projects coming to town. If anything, she says, he sought too much input at times when he just needed to make a decision. But Nickels’ staff rarely asked her to weigh in at all. “When Greg took over, it was clear—I was running the film office at this point—you didn’t get the sense that anyone cared what you thought,” she says.

Nickels’ staff also exerted unusual levels of control. James says she got into trouble for making a lobbying trip to Olympia without first notifying them. When they found out about the trip, she says, the mayor’s office went to the city council asking that her position be moved under the umbrella of the Arts Commission, which effectively would have eliminated her job. The council voted down the move, but things stayed tense with Nickels’ office until she retired in 2005, James says. Under the Nickels administration, “people become turf-builders,” she says.

Ceis says the city did reprimand James over the Olympia trip. “She wasn’t a free agent when it came to legislative affairs,” he says. “I guess in the past she may have had that freedom.” But Ceis denies that they tried to eliminate her job as a result. He says moving her position to the Arts Commission was an attempt to cut costs by consolidating departments.

Steinbrueck says hostility wasn’t limited to the administration’s own employees. Nickels asked his department heads to submit weekly reports on various goings-on in the city. Steinbrueck claims those reports were mostly just rat sheets. He once got access to one that reported on what Steinbrueck had thought was just a casual hallway conversation with a city manager. “That creates an air of suspicion and discomfort, you know,” he says.

Ceis confirms that the reports exist and makes no apologies for them. “Yes, well, they work for us, we like to know what they’re doing,” he says. “As we know, in the case of [the Department of Transportation, which has been plagued by allegations of mismanagement in recent weeks], he’s accountable for their performance.”

For his part, Nickels says differing views among people in government is a natural part of the process, and he does listen to concerns. “I think tension is fine, disagreement is fine,” he says.

Things are a little more direct in Chicago. Richard M. Daley accused a rookie alderman of racism for failing to support a children’s museum on the south side. Another time he warned city council members that if they opposed a planned increase in the Chicago transit budget, it would so anger their constituents that they would need police and fire protection for their families. Warned Daley: “You’ll last half a day.”

The Fear

In 2001, the city came up with a plan to put a median down the center of Aurora Avenue from North 110th Street to North 145th. The median was intended to reduce accidents that occur when cars make left turns across speeding traffic. Business owners hated the idea because it would limit drivers’ ability to pull into stores on the opposite side of the street, since the median would be crossable only at major intersections. But after a couple of community meetings, it became clear the city planned to go ahead with the project regardless of business owners’ concerns, says Faye Garneau, head of the Aurora Avenue Merchants Association.

Garneau says the Association finally realized that the only way to fight the plan would be to appeal it through the city’s Department of Planning and Development. The easiest way to derail the project, their lawyer told them, would be to have it thrown out on environmental grounds. So they started looking for someone to do a water study that could show problems with runoff if the median was constructed.

And that was where they ran into Nickels’ reputation. According to Garneau, every hydrologist they contacted in Seattle said they didn’t want to be involved in killing a project the mayor was backing. The Association finally found a hydrologist in Olympia able to convince the Planning Department that the city had not adequately accounted for runoff, and the project was put on hold.

Garneau says her organization has had disagreements with previous mayors, and she thinks government in general “appears to have an arrogance about it.” But Nickels, she adds, has been especially difficult to work with.

“I wouldn’t go so far as to say that Nickels bullies people,” says one local builder who did not want to be named, “but there’s certainly a fear that people have of associating themselves with someone that would compete against him in the mayor’s race.”

Chicago has a different approach to infrastructure. In 2003, when Daley decided he wanted to build a park at the location of an airstrip on a peninsula jutting into Lake Michigan, he waited for no one. Daley was in the middle of disagreements with the state and federal governments over how to manage the airstrip when he finally just ordered a bulldozer crew to destroy the landing strip and control tower.

The Hard Stance

Joe Quintana, a onetime friend and consultant to Nickels, calls Nickels’ first term in office one of the greatest in Seattle history. “He did a lot in turning this city around when its knees had buckled from the repeated blows of WTO, the dot-com bust, and Boeing’s departure from the region,” Quintana says. (Boeing moved its headquarters to, yes, Chicago in 2001.)

But after that first term, Quintana believes hubris set in, and Nickels began approaching things with an attitude of “You must do it our way or it’s not going to happen.” As evidence, he points to the amount of time it took to finalize a move to get the largely industrial Interbay area rezoned for apartments and grocery stores.

Interbay Neighborhood Association Executive Director Bruce Wynn believes Nickels and the executive branch at City Hall held up the Interbay rezone for four years as payback when residents rejected the mayor’s plan to make it an industrial-only area. Wynn says the rezone was largely favored by nearby residents of Queen Anne and Magnolia, and by some of the manufacturers, who liked the idea of their employees being able to live closer. “Everyone wanted to see this neighborhood developed,” he says.

The city council was on board, but the mayor’s office blocked the project, Wynn and Quintana claim. By the time the rezone finally got through last year, Wynn says, the real-estate market had crashed and they couldn’t get developers to start building in the area. Though there are signs of life: The Seattle Storm recently moved its headquarters to Interbay and a Whole Foods store is set to open there this fall.

Ceis disputes Quintana and Wynn’s account. The mayor’s staff was intentionally holding up the project, he says, but not because they wanted to keep it industrial. Ceis says that the Neighborhood Association didn’t want to include low-income housing. In 2007, two years after the Association had sought to get the area rezoned to allow bigger residential and retail developments, Nickels came up with a proposal to require developers seeking a rezone to set aside 11 percent of their buildings for low-income housing. The Association felt it should be exempted since it had put in its application before the Mayor proposed what came to be known as “incentive zoning.”

The mayor’s office dug in its heels. Only when the Association agreed to have low-income apartments included in any new development did the city allow the plan to go forward, Ceis says. “If they’re accusing us of Chicago politics, they’re going to have to come up with something different,” says Ceis. “[Chicago] is harder ball than that; those are just policy disagreements.”

Low-income housing has also loomed large in southeast Seattle, where activist Pat Murakami has accused Nickels of shoving undesirable facilities down the neighborhood’s throat. The Southeast District Council is one of 13 official neighborhood advisory groups to the city, consisting of various local organizations, from Murakami’s Mount Baker Community Club to the Tenants Union. Each group has one voting member. Murakami believes Nickels’ administration compelled some of the representatives to promote low-income developments in the neighborhood, rewarding them in turn. As evidence, she points to council president Leslie Miller’s appointment by Nickels to the Seattle Planning Commission—an unpaid position.

Ceis calls the allegation that Nickels stacked the council “ridiculous.” He notes that in order to serve in a leadership role, Miller had to be elected by the current council members.

Nickels says he just can’t make everyone happy when it comes to actually deciding when, where, and how to develop the city. “At the end of it, I make a decision and move forward,” he says.

In Chicago, manipulation of smaller neighborhoods is better-documented. The city is divided into 50 wards, each with an alderman, the equivalent of a city council member. There are also ward bosses whose official job is like a precinct committee chair for the local Dems, but historically more like a political emissary of the mayor. Want better trash pickup in your ward? Get people in it to vote for the Daleys. Ward bosses and leaders who do well are rewarded with lucrative city jobs. It became so rampant that in 2006 Robert Sorich, known throughout Chicagoland as Daley’s “Patronage Chief,” was sentenced to 46 months for his role in doling out lucrative city jobs to political allies.

The Big-Money Alliance

If Nickels has been maligned for promoting low-income housing, he’s also been criticized for steamrolling the massive redevelopment of formerly blue-collar South Lake Union into an urban village for the affluent.

In 2003, Nickels created the South Lake Union Action Agenda—$500 million worth of proposals to expand Mercer Street, build a streetcar, put in a park, and bring more electrical and water capacity to the area to power the labs and biotech firms that Paul Allen, the primary South Lake Union landowner, hoped to bring to the area. The development since then, which includes the streetcar and upzones that enticed Amazon.com to move to a 160-foot Vulcan-owned building, have given Nickels a reputation for being in Allen’s pocket.

The money invested by the city in the area is “so out of proportion—the attention and allocation of resources—it can only be explained by the tight, special relationship [Nickels] has with one of the wealthiest men in the world.” So says John Fox of the low-income housing-advocacy group the Seattle Displacement Coalition. He calls the infrastructure improvements a giveaway to Allen. His organization got involved when Allen initiated plans to level the low-income Lillian Apartments. Fox’s group lost an effort to save the building.

Since he first ran for mayor, Nickels has received nearly $6,000 in campaign contributions from Vulcan employees, according to the Public Disclosure Commission. That’s more than any other candidate for local or statewide office has received from Vulcan staff, including other incumbents running over several years.

There’s one call every Illinois politician—from the mayor to our beloved President—has absolutely had to make when running for office: Tony Rezko, who’s raised millions for nearly every officeholder in the state. That is, until last summer, when he was found guilty on 16 charges related to a multimillion-dollar kickback scheme he operated to funnel state contracts to businesses. His full sentence has yet to be decided, so for now he calls the Chicago Metropolitan Correctional Center home. When it comes to shady political associations, Rezko is hard to beat.

The Muscle

Behind every great heavy-handed mayor is the muscle. Nickels has Ceis, otherwise known as “The Shark.” (Nicknames are a hallmark of every respectable Chicago thug.)

A year after Nickels took office, Ceis made headlines when he passed a note to then–City Council member Jim Compton, chair of the city’s police and fire committee, in the middle of a contentious vote over potential cuts to the mayor’s budget. The note threatened to cut funding for a new fire engine for Green Lake if Compton didn’t vote to keep the mayor’s budget level steady.

Green Lake residents had written to the council in droves, according to a press release at the time by council member Nick Licata, asking that the council fund the truck. The Seattle Times filed a public disclosure request with Compton’s office and got the actual note, written by city finance director Dwight Dively. “Because of the Council’s vote on the Mayor’s office budget, we can’t promise the money for Attack 16 [the fire truck] now. Sorry.” Compton changed his vote.

Ceis says he and Compton had reached an agreement on what to fund in the budget, but then Compton started voting against that agreement. “Mr. Compton apparently didn’t remember or something went wrong in his head,” Ceis says. So he passed the note as an unsubtle memory jog. “And then he remembered and started voting the right way.”

The Seattle Times also reported an incident in which Ceis called lobbyist Martin ‘Jamie’ Durkan when Durkan’s client, the Tukwila City Council, voted against proposed light-rail routes. Durkan told the Times that Ceis told him he was through in local politics—and tossed in a few profanities for good measure. In interviews with Seattle Weekly, more than one person said that Ceis has a reputation for making people cry in meetings.

When it comes to applying direct political pressure from serious muscle, the winner is former Chicago Mayor William Hale Thompson. After being ousted by reformers in 1923, he came back four years later with Al Capone on board to help his re-election. Ceis passed a note and threatened to take away fire trucks; Capone passed bullets and threatened to take away kneecaps. Thompson swept back into office.

That Bad?

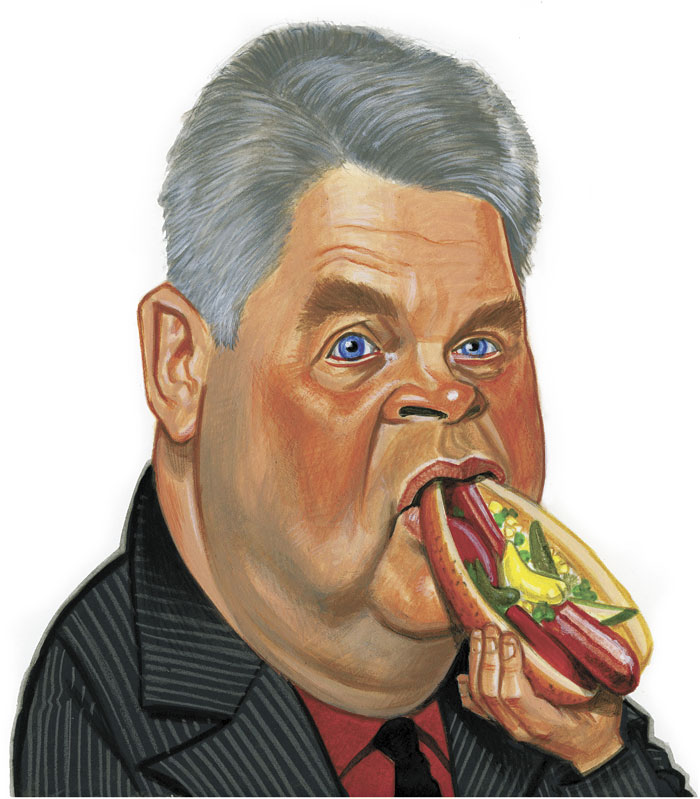

Nickels and Richard M. Daley do know each other—they appeared together in a Vanity Fair “green issue” in 2006, which featured the two, along with several other big-city mayors, striking visionary poses. Nickels earned the recognition for having called on mayors across the nation to voluntarily commit their cities to the Kyoto emissions standards after the federal government declined to sign. A former staffer also once gave Nickels a vintage copy of Newsweek with Richard J. Daley on the cover, saying Nickels reminded her of the former Chicago boss. There is something undeniably Chicago-like about our mayor’s “husky” appearance.

And really, would it be so bad if we had a Daley-style leader in charge? Even Rankin admits that while she found Nickels’ predecessor pleasant to work for, she didn’t always feel he was effective. [In his Seattle Times column this past Sunday, Danny Westneat argued that the arrival of light rail was a sign Seattle is growing up, becoming a little more Chicago-style, and that’s a good thing.] You can’t help thinking that if we’d had someone that aggressive at the helm, we might have handled the viaduct problem long ago, and installed city-wide rail lines to boot.

Though that might have come at the cost of cement shoes fitted to a size Peter Steinbrueck.

[This story has been corrected since it was first posted. It originally described Jan Drago as a “former” member of the city council. Drago is retiring from the council this year, but is still an active council member.]