Editor’s Note:

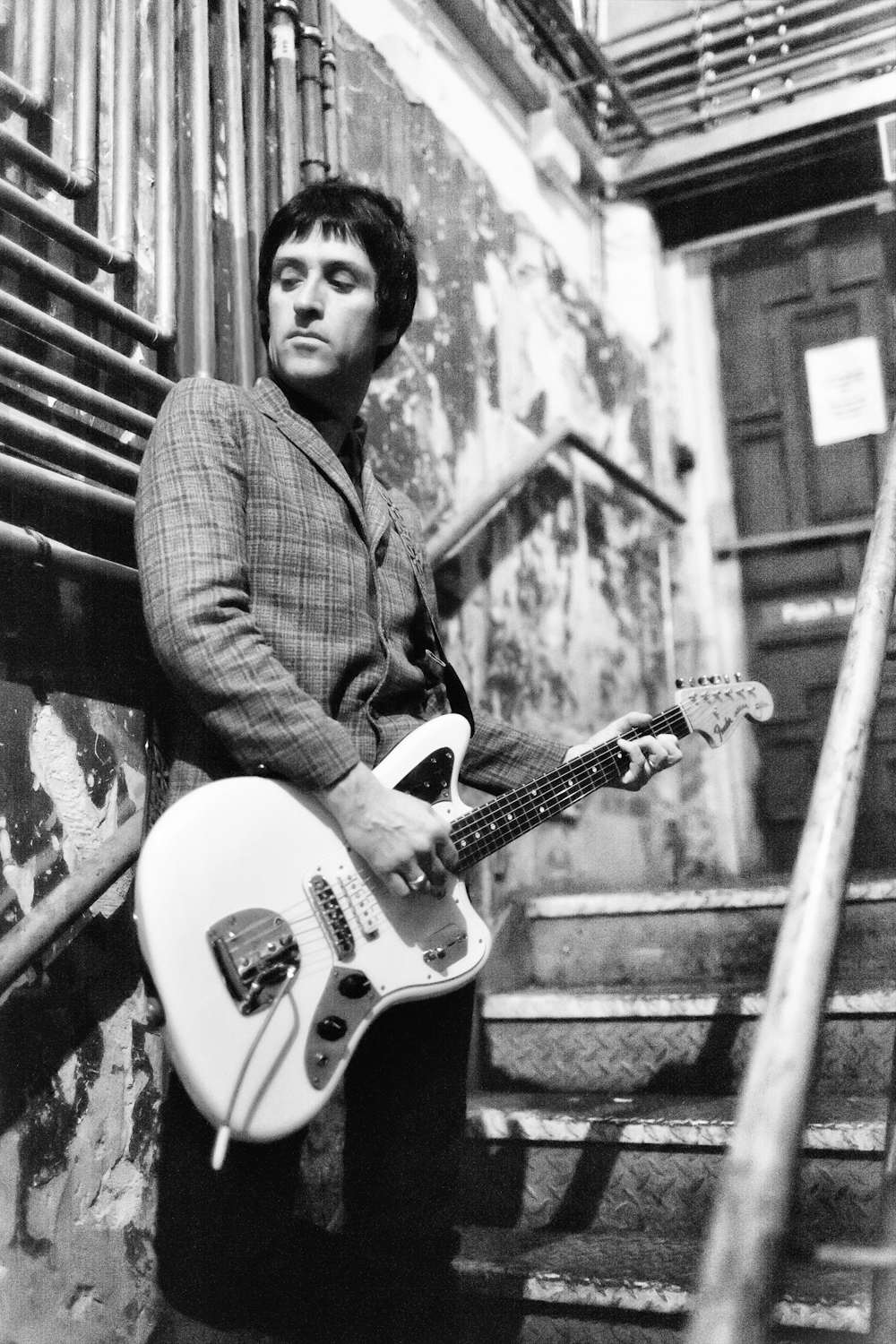

With Johnny Marr coming to Neumos on April 15 to promote his new album, The Messenger, we dispatched SW columnist Duff McKagan to interview the former Smiths guitarist. It took professionals in New York and Seattle to get the boys in Manchester and Los Angeles together on the phone. Here’s what transpired:

Marr: Hey, Duff?

McKagan: Hey, Johnny, how are you?

I’m very well, thank you. How’s it going?

Good. I think we could have just done this, me calling you. It’s pretty official this way, isn’t it?

Yeah, we’ve gotta be guarded. We’re being guarded by those who must be obeyed. But, nice to talk to you, man.

I feel like I know you, dude, because I’ve known [The Cult’s] Billy [Duffy] for so long, and he talks so favorably of you, and I know you guys are mates.

Yeah, likewise, Duff. I guess Billy’s the person I’ve known longer than anyone else. The neighborhood we grew up in was really cool, it was very working-class. We would just know and dissect about everyone who was making a record at the time, and I look back on it now and I think, wow, that was really quite a cool apprenticeship.

You were sort of the anti-guitar hero. I’m just so fascinated by your guitar style. I know Manchester. I know what Billy Duffy has told me. I try to picture you guys in 1979 or whatever. I don’t know what you were listening to to get that sound.

Joy Division were rehearsing in the room above my band, and they were scary guys just to look at because they wore old-men’s clothes. Very austere, grey, thrift-store stuff going on. Haircuts that looked like they just fought the Second World War. That was much scarier than someone who looked like one of the New York Golds or the Rolling Stones. It was so off-paced.

My thing was getting invited to play with other bands, because I had the knack and a certain kind of facility. Certain things came easy to me, I guess, riffs that were going around at the time. Everyone would be trading riffs, almost like currency. If you could play “Rebel Rebel” without sticking your tongue out, that was impressive stuff.

My family was obsessed with records, so as a little boy, my favorite toy was a little toy guitar. So I had a thing for the guitar much younger than all of my mates. I would think about the shape of it and all of that—it wasn’t for the fame and fortune or getting girls or anything, I really just loved this little wooden guitar as a boy. I would always be upgrading that.

Around 11, I was very keen to be able to write some songs on it and put songs together. I think the big influence on my playing was that was the same time I was able to start buying 45s with my money, and I am still obsessive about 45s. Both those things at the same time: being able to hold chords down and buying chart music of the day, which I am still not a total snob about.

What were those 45s?

The 45s were things like “Amateur Hour” by Sparks; “All the Young Dudes” by Mott the Hoople; all the T. Rex songs; and some of the songs by The Sweet, The Glitter Band. I guess in the U.S. it’s called bubblegum, but it was just regular chart music.

I got very lucky because that very commercial music was really based on guitars. There were so many riffs and they followed that commercial single format.

I was very young to start playing, but I was very serious about learning to play. I wasn’t necessarily isolating the guitar part—something done on an organ or a bass line, I tried to play it on the acoustic guitar. Still, when I write or play a song, I’m trying to play a whole record, really. Does that make sense?

It totally makes sense. I grew up in the same sort of big musical family. As a kid, music was just this magical thing.

You’ve moved back to Manchester, is that right?

I moved back from Portland deliberately. I knew I was into writing a big number of songs, which has resulted in this new record The Messenger. The Cribs were still touring, so I was playing with them at that time. I knew when I did get off the road, I would start writing that. There was a very, very kind of faint echo in the back of my mind; I didn’t try to overanalyze, but I recognized [it] as being enthusiasm to sort of catch the vibe that made me excited when I was a schoolboy and performing before the Smiths.

I kind of just—almost on a kind of superstitious hunt—I thought, if I go back to the UK, Manchester particularly, that will get me closer to the vibe.

I went on this intuition that these songs should be pretty exciting and up-tempo, good to play live, [in the] spirit of the sort of things that you liked when you were a kid.

You’ve kept yourself really current. I’m sure that’s not something you’ve tried to do. You’re just doing your thing. I just really appreciate that about you.

Again, you know, something you’ll probably understand as a musician, but when I was invited to play with Modest Mouse, they were complete strangers to me. I took up that invitation somewhat skeptically, because I wasn’t sure if it was going to work.

After all the members convened—it’s a rag-taggle, strange bunch of people with odd kinds of instruments—I was sitting in the middle of the room working on the riffs, and I went: “I don’t know what this is, but I like working with these guys.” That reminded me of when I was a kid—when you’re not good enough to analyze or copy but you just plug in. I like to think that I never really lost that connection with that person.

When I was playing with the Cribs, they came to my studio—which is nice and big in the countryside—but then we went out to the warehouse in the industrial north, because I wanted to write and rehearse there.

When we were moving all the gear into the service elevator together, I was thinking “We’re all the same, we’ll load the gear.” It doesn’t matter how many records we’ve sold, fans we have, or what we’ve so-called achieved. It’s a connection to who you were when you’re younger, and if that’s the main reason you do it, no one can take that away from you.

That’s inspirational. I’m glad you’re around and doing it.

Well, thank you very much, man. How was writing the book? Did you enjoy that? Was it difficult?

It was tough, Johnny. I enjoyed it. It doesn’t sound like you go back in time and think about the old days of when you were 22, and I don’t either. I’ve got kids, and life just goes forward—you don’t have time to think about when you were 15 or when you were 25. Writing about the particular story I wrote about—kind of like how I fell into addiction and my way out—was rewarding, but I wouldn’t want to do it again.

I think I’m going to do it, but I’ll wait a couple years. But I can’t wait too long, ’cause I’ll start forgetting stuff.

You know, I didn’t write the stuff I forgot about. I kept it pretty simple. I didn’t try to dig through old tour books or any of that crap. I just wrote about what I remembered.

I guess [publishers] want me to give a load of dirt . . . obviously I’m not gonna do that. I’ve got a load of stories like yourself. I’ve played with so many different musicians, just casually. Whether it’s David Crosby on the end of his bed or hanging out with Keith Richards, all of that stuff. People are kind of fascinated by it.

I’ll tackle it one day in the not-too-distant future. I wanna do a couple more records, praise God. I’ll get that done, and then I’ll take some time out and do that.

I’d love to hang out and shoot the shit. Also, it’s great for me to speak to someone who doesn’t say, “Hey, when’s your old band gonna reform?”

Johnny, I get the same interviews.

[Laughs] Let’s get together and catch up. I wanna see ya, and all the best to your family. Keep doing it, man. It’s great.

Cheers. Thanks, Johnny.

askduff@seattleweekly.com

JOHNNY MARR With Alamar. Neumos, 925 E. Pike St., 709-9467, neumos.com. $27 adv. 21 and over. 8 p.m. Mon., April 15.