BOULANGERIE 2200 N. 45th St. in WALLINGFORD, 206-679-2319 7 a.m.-7 p.m., Tues.-Sun.

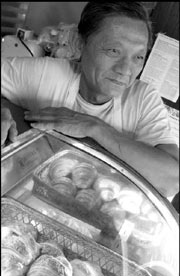

Xon Danh Luong would have a story to tell, if he had time to tell it. Usually, he’s too busy. Six days a week, Luong begins before dawn, baking French artisan breads and pastries in his Wallingford bakery, Boulangerie, then minds the busy corner shop through the evening. A lot of people got into baking about when he did, looking for a more fulfilling lifestyle. Luong likes his trade, but it’s less a labor of love than a means of getting by. That’s what his story’s about: simply getting by.

He didn’t always own the shop. Now 54, he started as a baker at Boulangerie 22 years ago. He was new to America, but not to French-style bread. Giang, Luong’s home province in southwest Vietnam, had long been under French colonial rule. When his father died, Luong and his older brother took over operation of their parents’ French-style bakery. Luong was 10 years old.

In 1968, he was drafted to fight for U.S.-backed South Vietnam in the Vietnam war. When war ceased, he went to work for a boat-refurbishing company, turning old fishing vessels into escape boats to ferry refugees out of war-ravaged Vietnam. For working there, Luong earned a spot on one of the boats in 1979, along with his wife and their 18-month-old daughter. Starting the trip as assistant captain, his navigational skills soon upped his rank. After six days at sea with as many as 600 refugees crowding the 80-foot vessel, he was captain, taking the boat to a sparsely populated Indonesian island. Building their oven and cooling racks from gathered stone and wood, he and his wife opened a makeshift bakery to help feed some of the thousands of refugees who shared their island camp.

After eight months and some inquiries by a U.S. human rights group, his family was granted entry to the United States. They were flown to Spokane, where a sponsor family waited. There, Luong took English classes until he saw an ad for a bread baker in a Seattle-based Vietnamese magazine. He went to Boulangerie on a three-day trial; he got the job the second day. He’d been in the U.S. four months.

Luong quickly moved up the ranks, learning to make the owners’ signature pastries and meat sandwiches, and became manager of the shop after the owners sold it to Thriftway in 1986. In 1995, Thriftway threw in the towel. Luong bought and saved Boulangerie, carrying on in his own tradition with the help of his wife and daughter.

The marriage dissolved almost a year ago, and his daughter has grown up and moved on. Since then, he’s run the shop virtually on his own. His strategy for survival: Keep costs down. It’s grown increasingly necessary as the economy’s worsened. He recently pared back his help to just three part-time employees, discontinued Boulangerie’s wholesale operation, and rigged up his own energy-saving mechanism for the shop’s refrigerator.

HE CONTINUES to do what he knows—baking the goods his customers know, the goods that have kept the shop afloat for more than 20 years: golden, flaky croissants (savory, flavorful ham and cheese, $2.60; demure, sweet almond, $2.35; a pleasant raspberry, $1.75), all not too heavy and flavored as they should be, with plenty of butter. There’s a sweet-and-tart chausson au pomme (fresh-apple puff pastry, $2.50); a moist, almond-kissed pithivier ($2.50); there are fruit tarts, dark chocolate truffles, and, for lunch, incredible meat sandwiches on fresh-baked, golden-crusted baguette ($4). The tender, high-quality, thickly cut sandwich meats like roast beef and salami easily make up for the unremarkable lettuce and heavy mayonnaise. The roast beef in particular, thick and tongue-like, will melt in your mouth, but not before making a delightful impression.

Boulangerie is small—just a display case, a beverage case, a drip coffee station. There are a few chairs, but most customers scurry out as quickly as they scurried in, leaving a trail of golden pastry flakes down the sidewalk behind them. For two decades, customers have seen the smiling man, first in the kitchen, glimpsed through an opening in the bread racks, eventually behind the counter. Maybe they say “Hello,” maybe they converse about the weather. But step into Boulangerie, order a pastry, sit down a while, and ask Luong how he’s feeling, and he might smile and tell you, fine, thank you. Ask again, and he might tell you he’s tired—still catching up from yesterday and last week and last year, 14 hours a day, six days a week. On Mondays, the shop is closed. Luong says that on Mondays, he likes to sleep for 12 hours before getting up to dig into his chore list. For Xon Danh Luong, this isn’t a sob story—it’s just his story. He’s worked hard just to have a story to tell.