Seattle authorities have been chasing homeless campers out of their hideaways for decades, but the current policy of rolling mass evictions didn’t begin until Mayor Ed Murray declared a formal State of Emergency in 2015. Since then, Seattle has increased spending on homelessness and housing—and on sweeps, of which there have been more than 1,000 in the past two years.

The evictions are inhumane and counterproductive, leaving people with no place to go, reshuffling the problem without solving it. But between now and the November 7 election, human-rights advocates have a unique window of opportunity to force leaders to fix the sweeps. There are three reasons why the time is ripe.

First, Murray recently resigned after months of mounting allegations that he sexually abused minors decades ago. During his tenure, he mastered the art of paying lip service to homeless campers’ humanity while simultaneously ordering police to chase them around the city. Now Murray is gone, and his brand is toxic, so his specific policies are vulnerable. It’s a rare moment when public pressure can circumvent the interests of the powerful, which in this case amount to the social cleansing of very poor people for the sake of business’ revenue and wealthy residents’ comfort.

Second, Seattle is anticipating a general election for mayor and two City Council seats. The candidates involved are susceptible to public pressure. So is the rest of the Council, to a lesser extent, because as survival-minded politicians they view these races as a weather vane for public sentiment. Campaign season is public-pressure season.

Third, homeless advocates are organized. The Housing for All Seattle coalition includes the Seattle Peoples Party, the Transit Riders Union, and dozens of other groups—largely the same group of activists who earlier this year successfully pressured city leaders to pass an unprecedented income tax. Now they want Seattle to quadruple its investment in subsidized affordable housing, expand shelter and authorized tent cities and tiny-house villages, and limit sweeps to homeless encampments in locations that are unsafe or unsuitable. In such cases, the city would have to direct the campers to an alternative campsite.

In their current form, sweeps serve a few functions: First, in addition to sometimes evicting people from (or into) especially dangerous or inconvenient locations, the evictions policy allows city leaders to respond to complaints from neighbors and businesses about unauthorized homeless camps by shuffling the campers off to some other neighborhood. Second, they allow city leaders to evade liability for anything bad that happens at unauthorized homeless encampments. Third, the sweeps are a club with which authorities figuratively beat homeless campers into shelters, which vary in safety, hygiene, and admissions criteria.

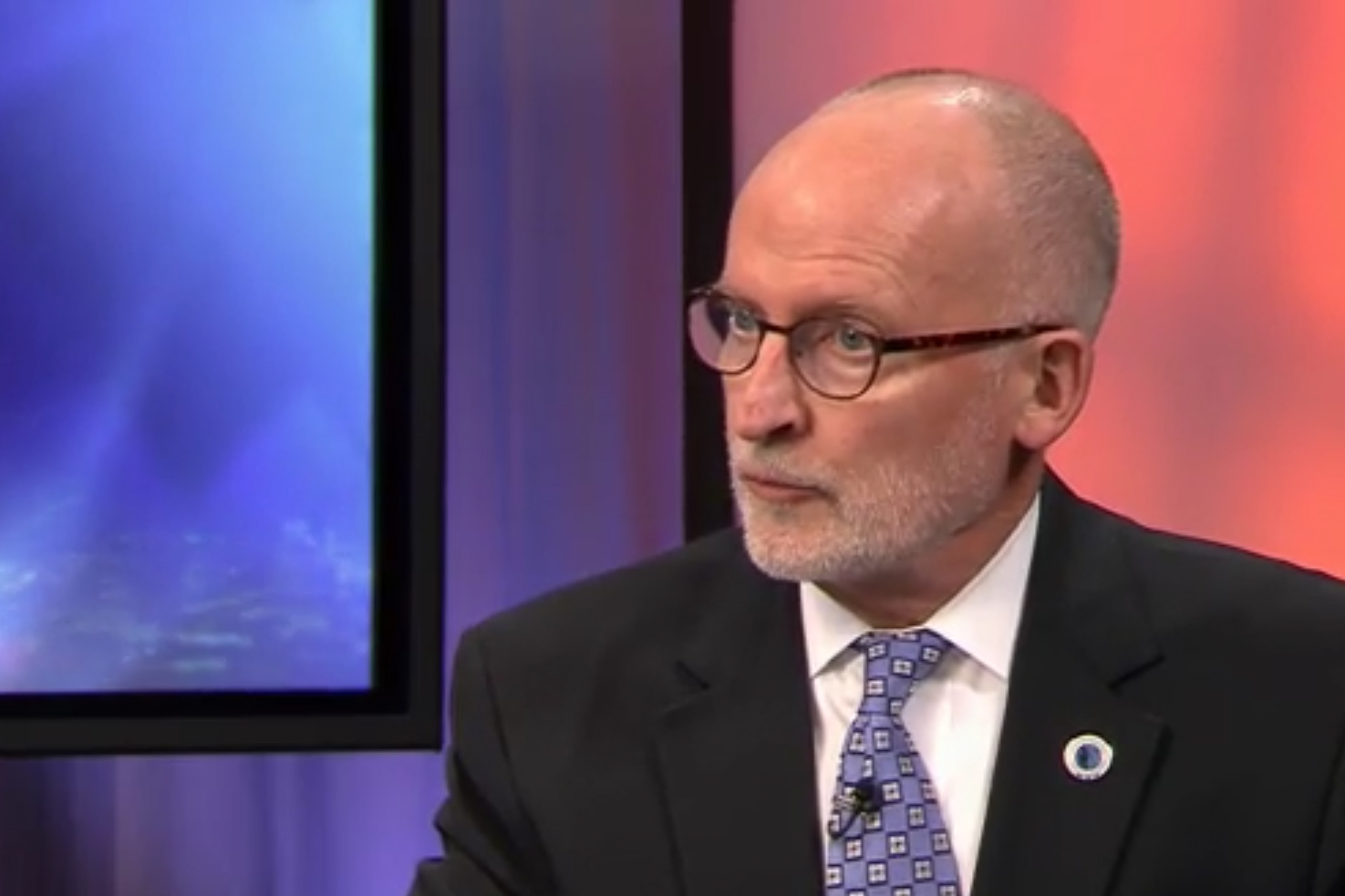

Interim Mayor Tim Burgess has supported the sweeps in the past, and has perhaps the worst record on homeless human rights of any current elected Seattle official. In 2010 he sponsored a bill to allow police to ticket panhandlers they deemed “aggressive.” The next two months present Burgess—by all accounts an honorable and caring man in his personal affairs—with a chance to make amends with homeless advocates. As the head of the executive branch, he can switch from a punitive model to one that reduces harm.

Last year we wrote that despite many stances of his we disagree with, “Burgess has always shown a knack for eschewing naked partisanship and political windstorms in favor of a singular pursuit of good governance.” This essential integrity inspires hope that the interim mayor might recognize the fundamental dysfunction of mass evictions, and use his remaining time in government to fix them.

But if past experience is any indication, he probably won’t. That’s OK. We can do this the hard way. In fact, some people have already gotten started. On the same day Murray resigned, two women from the Southeast Seattle Neighborhood Action Coalition (NAC) chose to be arrested in protest of an encampment eviction in SoDo.

One of them, Eliana Scott-Thoennes, explained her stubborn decency afterward in a statement. “No, I will not walk away from neighbors,” she said. “No, I will not turn my head as we waste our city’s energy and resources on failed solutions that are causing needless harm. No, I will not accept the assertion that it is dangerous for me to stay to help people pack, to offer a friendly word, to stand by their side as they are being displaced. And when I see our officials criminalizing that peaceful, non-obstructive solidarity, I will resist.”

editorial@seattleweekly.com