Currently at Henry Art Gallery, the exhibition Changing Forms excavates the luminous, underrated work of video artist Doris Totten Chase. The retrospective joins the larger resurgence of interest in the earliest female creators of media art. For a timely exhibition, timely questions: Are women remembered as feminists by virtue of arriving first in a field? How do we celebrate Chase beyond this early arrival, and by her embodiments of a particular feminist ethos?

Chase was born in 1923, and until 1972 lived in Seattle with her family. You may have climbed her voluminous sculptures, Changing Form (1971) at Kerry Park in Queen Anne and Moon Gates (1999) at Seattle Center. Her son, Randy Chase, tells me that he remembers going to art events with her during his childhood, including to the Henry. She was integrated in the local arts community and taught painting at Edison Tech, now Seattle Central Community College. Randy recalls that for a time she supported the family as a teaching artist—astonishing by today’s standards. “At the time, society’s matrons would go learn to paint,” he explained. “She made social standing in Seattle because she was a lot of people’s art teachers.”

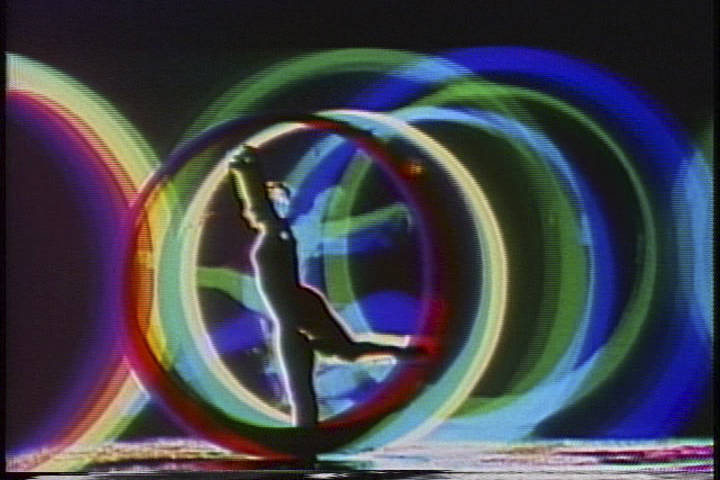

Her work was multi-disciplined, and Changing Forms traces Chase’s progression from object-based media like painting and sculpture to hybrid, time-based media, such as her signature “videodances.” As she moved from one medium to another, she maintained signature designs and concepts: oversized, wheel-like props that she constructed for live performances with dancers, which were recorded and turned into videos. They were reminiscent of her earlier Bauhaus-esque, modular sculptures, initially carved from wood and then fabricated on a large scale.

Circles 1 (1970) is regarded as one of the first computer films. Well before computer hardware and software became widely available, Chase used computers from Boeing, then, after moving to New York City, the image-processing equipment of WNET’s television lab and the Experimental Television Center. Her technical signatures included colorizers, which altered hues to bright neons; sequencers to create collage-like spliced layers; and synthesizers for multilayered images. The videos are auroral, drenched in color and fluid in movement. In Circles 2 (1971), dancers and sculpture are abstracted into one kaleidoscopic entity.

It is perhaps hard to imagine today, but making videos to convey feeling instead of exploring technical possibilities, especially as an untrained technician, was controversial. Art historian Ann-Sargent Wooster (in Patricia Failing’s book Doris Chase Artist in Motion) writes that video theoreticians such as Woody Vasulka understood the exploration of the video artist to be a technical one, believing that “if you don’t understand the soul of the machine (i.e., the physics of the machine), you cannot use it in your art.” Chase used computers for experimentation and play, prioritizing new forms of expression over technical mastery.

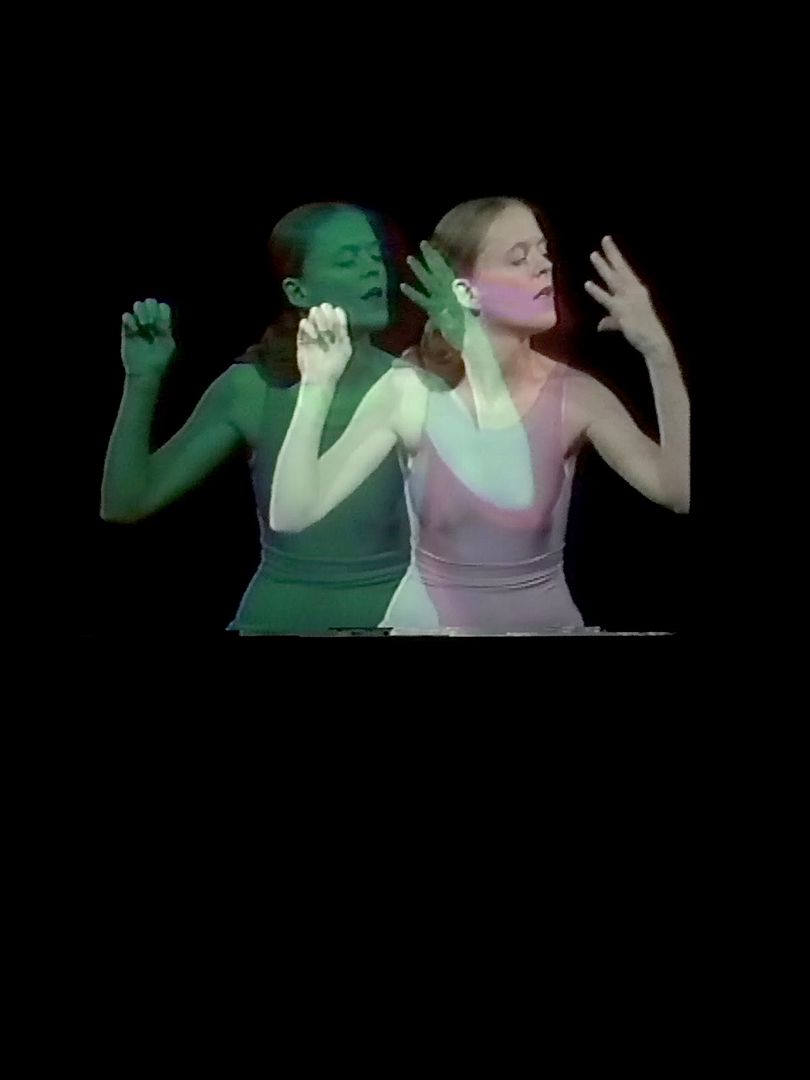

The special effects highlight the works’ emotional underpinnings. My favorite piece in Changing Forms is Window (1981, from the Concept series), in which actress Claudia Bruce performs a monologue with a complex range of emotions. Chase uses the camera effect of debeaming, which extends the dancer’s body and creates a sense of doubling. The effect dramatizes Bruce’s performance and adds a psychological effect to the dancer wrestling with her dualities, maybe the conscious and subconscious.

Window (from the Concept series). 1981. Single-channel video (color, sound). Photo by Minh Nguyen

Window (from the Concept series). 1981. Single-channel video (color, sound). Photo by Minh Nguyen

“Generationally she was a bit older than the second-wave feminists we associated with feminist video art,” art historian Johanna Gosse notes. Chase’s work, especially from the ’70s and ’80s, “is in step with the feminist politics of the era, which emphasized the body as a site of sexual and political liberation.” Chase’s work can be studied alongside the second-wave feminist principles of rooting knowledge through the body, ’70s new-wave therapeutic art, and Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique, which appealed especially to highly educated white, middle-class housewives.

Throughout her career, Chase sought collaborators, another key component of her feminist ethos. “Chase often worked with others and used collaboration as a method for both pushing the boundaries of her practice and divesting her work of singular authorship,” says Gosse. One major pivot in Chase’s collaborative work was choreographer Mary Staton’s invitation to create large kinetic sculptures, which resulted in a multimedia production for Seattle Opera. Collaboration with dancers, composers, and artists are prominent features of her ’70s and ’80s work, such as Dance Frame (1978), Jazz Dance (1979), and Travels in the Combat Zone (1982).

In Seattle, Chase was affiliated with the Northwest School of painting; upon moving to NYC in 1972, she worked in a milieu that included Stan VanDerBeek, Nam June Paik, and other artists interested in working with the latest media technologies. Gosse suggests looking to the works of Lillian F. Schwartz, another early computer artist who is receiving posthumous recognition, and a member of the Experiments in Art and Technology group that fostered collaborations between artists and engineers. Others in experimental film and video art who also worked with dance and performance include Carolee Schneemann, Shirley Clark, Shigeko Kubota, Charlotte Moorman, Joan Jonas, Martha Rosler, Yvonne Rainer, and Trisha Brown. The canon of early feminist video art remains largely dominated by white women, potentially due to questions of access to technology, and perhaps inadequate documentation.

The most radical thing about Chase may not be a video piece, but rather that cross-country move: When she was nearly 50, Chase packed up her life and moved into the Chelsea Hotel, then known for attracting queer, bohemian artists and writers. Chase lived there and worked voraciously on art until returning to Seattle in her 80s, closing her chromatic life of risk and experimentation.

Doris Totten Chase: Changing Forms, Henry Art Gallery, 4100 15th Ave. N.E., henryart.org.. Ends Sun., Oct. 1.

visualarts@seattleweekly.com