First, the bad news: King County Metro is about to raise its fares again by quarter—the fifth increase since 2008. Between then and March 1, when the new fares go into effect, off-peak fares will have doubled. That’s some serious inflation, which has not gone unnoticed even by a middle-class rider like myself.

Now, the good news: Low-income riders will get a break. As of March, those earning 200 percent of the federal poverty line (currently $23,000 for an individual) will be able to use a discount “ORCA LIFT” card that will cut fares for busses and light rail nearly in half, to $1.50 during off-peak times. Riders can sign up immediately, and in fact, during a soft launch that has been going on since October, 100 people have already done so.

This makes Metro only the second transportation system in the country to have this kind of discount program, according to the county, which unveiled it today for a handful of reporters. And the first, San Francisco’s, requires users to come back every month for validation, Metro’s Rochelle Ogershok explained. The ORCA LIFT card, in contrast, will be good for two years.

“We’re charting new territory,” Ogershok said, standing outside a little, Pioneer Square office where riders can sign up. How many will do so remain to be seen, but it’s possible the county will be flooded. It estimates up to 100,000 riders are eligible.

What makes this a potentially bigger deal is that the county is trying at the same time to coordinate and simplify all the discount programs available to low-income people by creating one-stop shopping storefronts. The Pioneer Square office, located in the county’s King Street Center on Jackson St., is one of 40 such locations throughout the country.

People may come in initally for an ORCA LIFT card. But, said county Executive Dow Constantine, who attended the press event today, “One of our strategies is…to ask the question: Do you have health care? Can we help them get signed up?” The newly-trained staffers working at these storefronts are trained to help navigate the state’s version of Obamacare, glitches and all. That might help the state Healthplanfinder exchange meet an ambitious goal it’s been having some problem with; for one thing, many people insured through the state last year haven’t renewed.

But the effort is about more than that. Staffers at these storefronts will also ask whether people need food subsidies, or help keeping the lights on, said Daphne Pie, a manger with Public Health Seattle & King County, which is jointly running the new effort with Metro. They can also help people get state and city childcare subsides, dental care, even free tax assistance.

Key to the concept is that people will only need to present their eligibility information once, avoiding endless duplications and hassles while maximizing assistance to them. It’s a nice idea, which recognizes that time is valuable for low-income people, like everyone else. Dow says it’s part of the county’s work of fighting inequity. As Seattle’s leaders do, he clearly sees local governments as playing the kind of big public policy role that used to be the exclusive domain of the feds.

And like all public policy, the nitty-gritty of how well it works will only become clear in time. Two low-income people came to the Pioneer Square storefront today to sign up for programs and meet journalists, at the county’s request. Both came as a result of their participation in the county drug court, which offers those charged with drug-related crimes an opportunity to avoid incarceration by undergoing treatment and fulfilling other obligations. They also receive practical support like an Orca card—one that will no longer be good when their participation in drug court ends.

And so a drug court advocate took Joshua Stanton and Chanh To the storefront today to get ORCA LIFT cards. A big draw for Stanton was also getting health insurance. “My past is starting to catch up with me,” said the rangy 30-year-old, referring to his former drug habit and the physical toll it has taken.

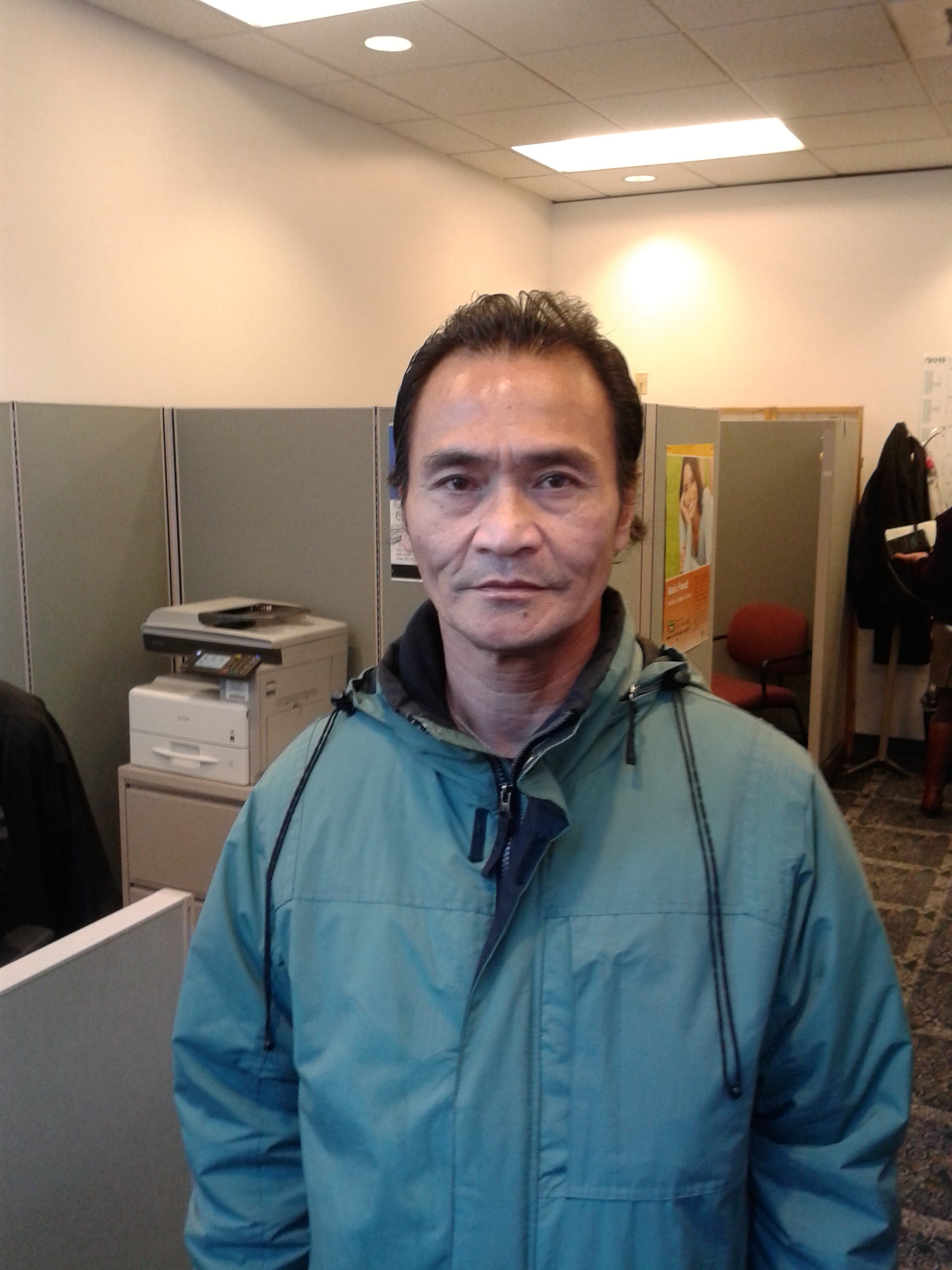

To, though, did not sign up for health insurance, even though he had none. At first, the Vietnamese immigrant said it was because he didn’t like hospitals. “I can smell the medication,” he said. “It makes me throw up.” At 57, he said he had never even been to a doctor.

But then he and the county’s Pie explained that he is not eligible for Obamacare because of his immigration status. Enrollees must show proof of legal residency for five years. To, who says he has lived in this country 32 years and whose family was killed for being close to Americans during the strife in his home country, once had a green card. But he let it expire. “It’s expensive” Pie said, referring to the cost of renewing green cards.

That puts To in a “black hole” when it comes to health care, she observed. So the county’s effort won’t be able to fix everything for everyone. But people should be be able to find out a lot more quickly and easily what help they can and can’t get.