At Guantanamo, we know, inmates are denied few possessions other than Korans and writing paper. Sharp objects are certainly not allowed, and their U.S. jailors strictly control photographs by press and visitors. One doesn’t want to add damning images to what’s already a huge PR problem.

This was also an issue for our government between 1942 and 1946, when roughly 120,000 Japanese-Americans, most of them citizens born in the U.S., were rounded up and sent to dusty camps far from the West Coast. It was worried that they’d somehow collaborate with the Japanese after Pearl Harbor, and President Roosevelt’s now notorious Executive Order 9066—upheld by the Supreme Court—resulted in the inland deportations, which began here on Bainbridge Island. A few of these internees were artists; some would become artists (like our own Roger Shimomura); but The Art of Gaman isn’t properly an art-museum exhibit. With over 120 objects, mostly created by amateurs from scrap materials, this is more of a history show. The art and craft examples here serve as supporting evidence, if you will, to one of the great American wrongs of the past century.

This touring show originated with the eponymous 2005 book by Bay Area curator Delphine Hirasuna, who visited BAM this summer to introduce the exhibit. As a child, she and her California family were sent to camps in Arkansas; one of her siblings was even born there while their father was off fighting the Nazis in Europe.

A puzzle created by internee Kametaro Matsumoto. Image via Terry Heffernan

“By and large, these people were not professional artists,” says Hirasuna. Their creations “were made by amateurs.” After the camps closed, in the rush to get home, “Most people threw them away.” Her own scholarly research began six decades later in the family attic, sorting through the boxes of her dead mother. Then she began canvassing nisei—the American-born second generation following the immigrant issei—who might have similar forgotten objects wrapped in yellowed newspapers from the late ’40s.

Though there were a few classes taught by professional artists in the camps, what one mostly sees here are the products of a pastime, not the deliberate effort to transform suffering into art. Self-censorship, the desire to be a “good” uncomplaining American, apparently precluded any political art or outraged expression. Hobby meets necessity in the improvised tools we see (chiefly shears and woodworking tools). Art supplies were few, so most of the objects here are mundane and generally utilitarian: ashtrays and pencil holders, smooth-sanded wooden canes, tea sets, baskets and furniture, inkwells and dolls, brooches and wooden sandals, quilts and clothing. One Kent man embossed a leather wallet with a barracks scene from Tule Lake, California; you can imagine him being reminded of the bitter experience every time he paid for something during the postwar years. (No re payment for this injustice came from the government until the compensation movement of the ’80s.)

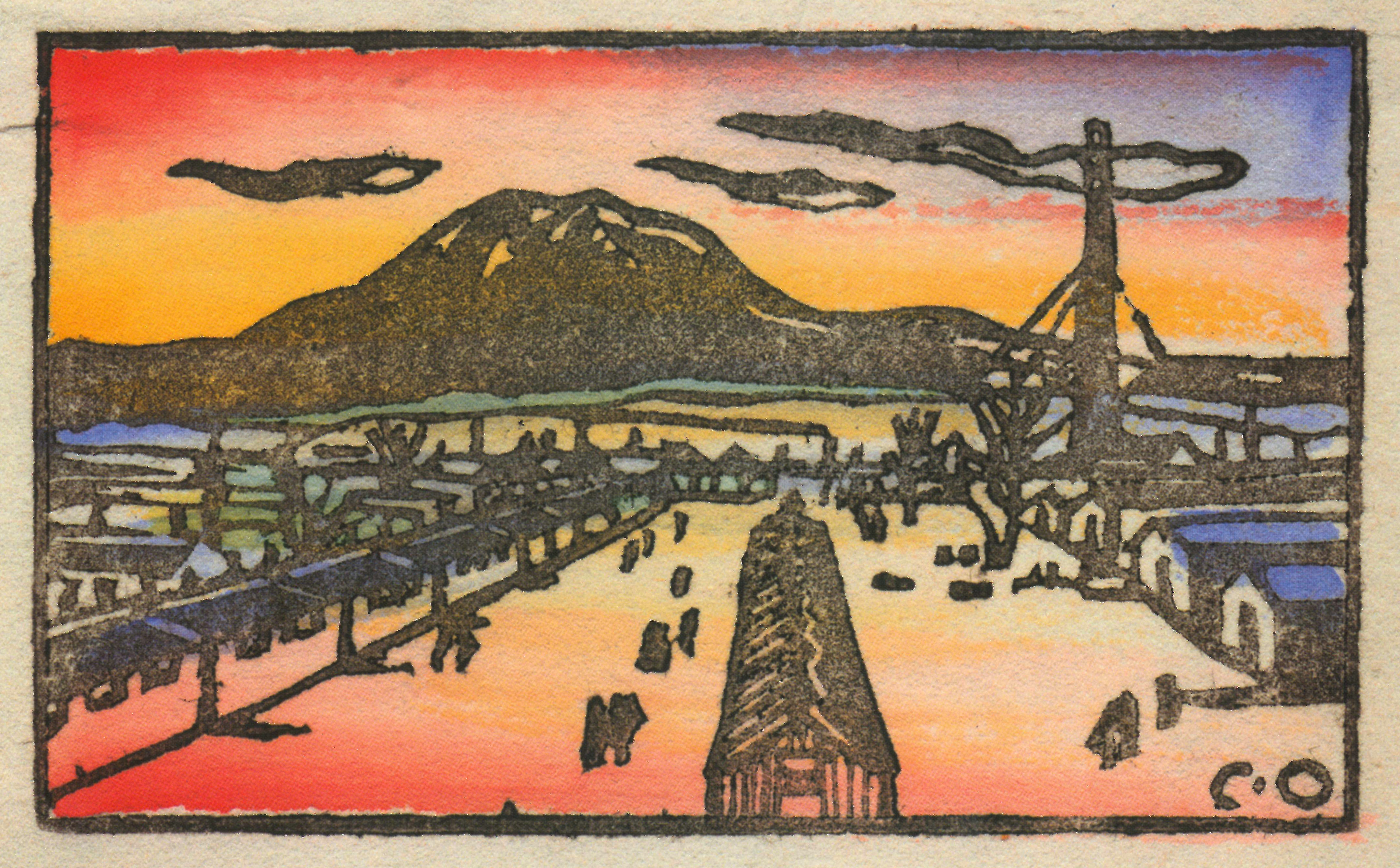

The more trained artists, like Chiura Obata and Henry Sugimoto, sometimes rendered the camps like traditional Japanese landscapes—only without the cherry blossoms and Mt. Fuji. Camps in Idaho, Wyoming, Arizona, and Utah were barren and unfamiliar compared to the Pacific Coast, where most internees had resided. Obata makes an effort to gentle the harshly regimented geometry of his Topaz, Utah, camp in a block-printed holiday card, the perspective lines leading to a distant mountain at sunset (west toward home), a scene washed in orange watercolor. The image is neither somber nor plaintive, which brings to mind the notion of gaman: “to endure the seemingly unbearable with patience and dignity.” There’s just a hint of beauty amid hardship, like a defiant flower in the ashes.

At Tule Lake, the teenaged George Tamura renders the barb wire, fencing, and guard towers more crisply, with none of Obata’s softening. There are no people, and his small watercolors have an almost industrial feel: Here is a plant, almost, for the manufacture of what? And where are the workers? Yet in the same camp, removed from Seattle, Suiki “Charles” Mikami subordinates the barracks to desolate nature. The clouds, bluffs, and snow make the camp seem puny—an unpleasant passing phase in the larger scheme of things. One moonlight scene, the snowy mountains reflecting lunar light, suggests Ansel Adams—represented in Hirasuna’s catalogue with a rare documentary photo at Manzanar, near where he famously shot in the Sierras. (A larger selection from his book Born Free and Equal was shown at the Bainbridge Island Historical Museum three years ago.)

The detainees themselves are usually omitted from such scenes. Hirasuna writes that “people, if pictured at all, were represented as insignificant, faceless figures.” To be maudlin, self-pitying, or bitter would be a form of surrender, a loss of face. Handicrafts were a way of keeping idleness and sorrow at bay. For that reason, I suppose, practical objects mostly took precedence over fanciful depiction. Many of these artifacts, more than 70 years old, seem deeply tactile: not just made by hand but often handled, like prayer beads. The issei, says Hirasuna, often favored wooden carvings of animals and other animist tokens of their birthplace. Yet even among the younger trained nisei artists, depictions of home are conspicuously absent, perhaps too painful to paint. Indeed, few of those homes were recovered after the war.

Mikami, who trained in Japan before emigrating to Seattle, depicts Topaz. Terry Heffernan

Here I should note that some of what I’m describing is from Hirasuna’s book (available in the gift shop), which is broader than the BAM show, which wasn’t yet fully installed during a summer press tour. The show has actually changed configurations several times during its travels, since many of its objects are on loan from family collections. To an extent, these artifacts are interchangeable: modest examples of folk art created during a brief time of particular hardship. They’d be better suited to a historical exhibit at MOHAI, for instance, augmented by more historical background materials.

Locally, this sad story was most famously told in David Guterson’s novel Snow Falling on Cedars, though the more direct connection here would be David Neiwert’s 2005 Strawberry Days. It’s a history of the displaced Japanese-Americans who farmed the Bellevue fields before the Lake Washington bridges made that land valuable for Miller Freeman and other developers. Bellevue Square and BAM now sit on their former fields. Compared to the humble keepsakes and heirlooms of The Art of Gaman, there are many more lovely, valuable things at the mall and museum today—but none stir such mixed emotions. Bellevue Arts Museum 510 Bellevue Way N.E., 425-519-0770, bellevuearts.org. $8–$10. 11 a.m.–6 p.m. Tues.–Sun. Ends Oct. 12.

bmiller@seattleweekly.com