Herman’s House

Runs Fri., June 7–Thurs., June 13 at Grand Illusion. Not Rated. 81 Minutes.

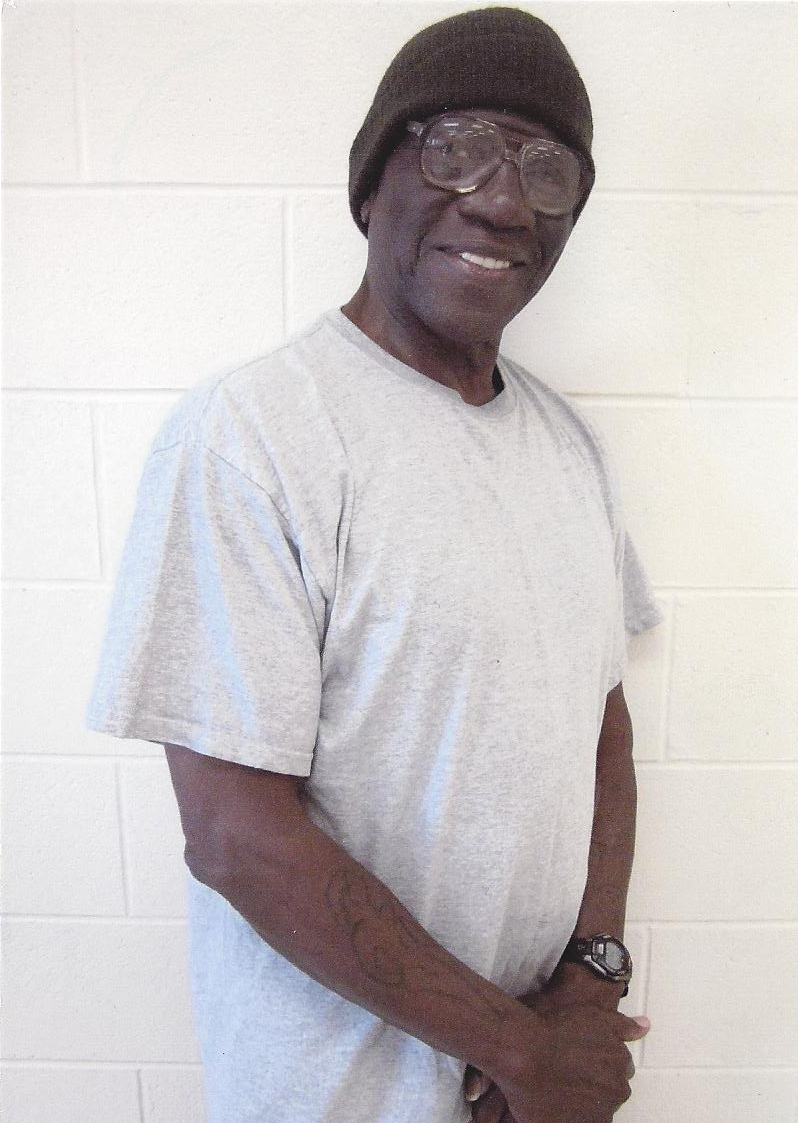

Artist Jackie Sumell had a neat idea: If the man who may be the longest-serving prisoner in solitary confinement in the United States could design his dream home, what would it look like? Herman Wallace has been in solitary in the Louisiana State Penitentiary for some 40 years, put there after being convicted of killing a prison guard—wrongfully, he says—during a prior sentence for bank robbery. Over a crackling phone line from behind the prison walls, Wallace narrates: He’d like flowers in the front, so visitors would feel welcomed. He’d like mirrored ceilings in his bedroom. And he’d like a six-by-nine-foot hot tub in the master bathroom. That’s a nice touch, since those are almost the exact dimensions of his prison cell.

Herman’s House often appears to be headed toward the politics of our nation’s incarceration policies, but every time it does, director Angad Singh Bhalla smartly steers it back to where it’s strongest: a story about hope, art, and the human spirit. That we never see Wallace’s face—he remains a detached, surprisingly upbeat voice speaking from a pay phone the entire film—only strengthens that theme. But Wallace isn’t Bhalla’s only source of pathos: After Sumell’s model of Wallace’s dream home is well received at art galleries, she launches an ambitious effort to actually build the house, so she moves to New Orleans to make it happen. (The art project, begun in 2002, took some four years to complete.) Meanwhile, Wallace is released from solitary confinement, and he has an appeal of his murder conviction pending.

The film could have been shorter: An impromptu debate between Sumell—a white Bay Area artist—and a black man about the Black Panthers is superfluous, if not a bit unsettling. (Wallace and two other incarcerated Panthers are known as the Angola 3.) But as documentaries on U.S. incarceration rates of minorities come fast and furious, Sumell and Wallace provide a nicely human entrance to the story. Daniel Person

PThe Kings of Summer

Opens Fri., June 7 at Harvard Exit and Lincoln Square. Rated R. 93 Minutes.

Maybe it’s a lingering childhood memory of the classic book My Side of the Mountain, or a weakness for a certain kind of afternoon-daydream movie, but The Kings of Summer fell directly into my sweet spot. The movie doesn’t exist in a real world (please don’t waste energy trying to reconcile psychological motives or social logistics), but in the enchanted realm of a teenage summer. Director Jordan Vogt-Roberts understands this charmed mood, which is why he layers the film with dewy inserts that would not be out of place in a Terrence Malick picture. The result is a nicely bittersweet ode to killing time and patching up differences.

We must begin by buying into screenwriter Chris Galetta’s implausible premise: Three high-school lads build a ramshackle house of their own in a clearing in some woods outside their suburban Ohio hometown. Joe (Seattle native Nick Robinson) has had it with his ill-equipped father (Nick Offerman); both are working through hostilities connected to the death of Joe’s mother. Joe’s friend Patrick (Gabriel Basso) is almost as disenchanted with his parents (Megan Mullally and Marc Evan Jackson), so he joins his bud for the adventure.

A nerdy classmate named Biaggio (Moises Arias) also takes up residence in the forest pad. Biaggio is not their friend, exactly, but he helps them construct the house, and he’s just . . . sort of . . . always . . . there. An intensely bizarre lad given to disconnected one-liners, Biaggio is typical of the movie’s odd vibe: He could not exist in real life, yet he’s completely recognizable as a certain kind of kid. A few weeks go by; the situation with Joe’s crush Kelly (Erin Moriarty) becomes very complicated; and the parents search for their boys. This missing-child scenario isn’t played in the elfin, stylized mode of Moonrise Kingdom, but it’s not realism either. Whatever it is, Vogt-Roberts is onto something.

You may have noticed the names of some TV-comedy regulars in the supporting cast. The Kings of Summer tosses the ball to these pros with gratifying regularity, which generates some of the jitterbugging rhythm of the 30 Rock school without sacrificing the piece’s wistful undertones. At times Vogt-Roberts—whose previous work has been in TV and shorts—catches the bounce of a Richard Lester–directed ’60s comedy, and he already knows where the camera should be for a joke to pay off.

Added bonus: With its tale of breaking away, the movie supplies its own metaphor as a quiet respite in the hustle and bustle of a blockbuster summer at the movies. For which, much thanks. Robert Horton

One Track Heart: The Story of Krishna Das

Runs Fri., June 7–Thurs., June 13 at Northwest Film Forum. Not Rated. 72 Minutes.

It’s easy to mock Jeff Kagel, a failed rock singer, spiritual seeker, and ex-cokehead who now performs chants for the adoring yoga crowd under the stage name Krishna Das. (He last played here at the Moore in 2010.) Like some baby boomers, Kagel dropped acid, dropped out, found a guru (Ram Dass, aka Richard Alpert, an LSD-embracing Harvard colleague of Timothy Leary), went to India to study at an ashram, then came back to the U.S. and wondered what it all meant. Jeremy Frindel’s too-admiring documentary isn’t out to mock Kagel, of course, but his veneration smothers what ought to be a more interesting, paradigmatic tale of ’60s spirituality.

Kagel, born in 1947, grew up Jewish on Long Island. Did he sing in the temple? Frindel doesn’t tell us. Later, performing with various rock bands, Kagel was supposedly invited to join Blue Oyster Cult—an assertion that no one in that group, or outside the doc’s very narrow sourcing, can substantiate. Today a gray-haired, sober, sympathetic presence, Kagel is allowed to present his personal history selectively and self-servingly. Frindel doesn’t question him, and his timeline of events is more than a little vague. (Kagel’s second act began in the mid-’90s with the album One Track Heart.) But nothing’s more American than self-invention and telling tall tales. If Kagel wants to call himself Krishna Das, fine. Frindel, however, is too caught up in the man’s aura to place him in any social or religious context.

Like the recent documentary The Source Family, about a silly yet benign California cult, One Track Heart is rooted in America’s second great spiritual awakening. Young Jews and Christians of the postwar generation suddenly started flocking to alternative forms of spirituality—Hindu, TM, Buddhist, mix-and-match, whatever. The Beatles weren’t the first to go to India (or to drop LSD), and Kagel is part of the same generational movement, that yearning to worship differently than one’s parents. He tangentially touches on that truth, saying about his ego, “Even when I think I’m a wave, I’m just ocean.” Frindel fails to follow that thread.

Kagel has performed with Sting, and Rick Rubin—seen here—produced one of his albums. Playing his harmonium and singing droning, Westernized kirtans, he now seems a happy, humble artist, content to play small rooms at premium prices (yoga class included). How many 66-year-old former rock stars can say the same? Brian Miller

The Prey

Opens Fri., June 7 at Oak Tree. Rated R. 102 Minutes.

The French maintain their love for good old American crime stories, and you could easily imagine The Prey as a black-and-white Warner Brothers melodrama from the 1930s. A bank robber, Franck (Albert Dupontel), calmly awaits the end of his prison sentence, his treasure buried safely in a tomb. His wife asks about the money, but he’s evasive. Prison thugs try to beat the information out of him, but he’s too tough for them. Then, in a moment of weakness/compassion, he lets slip the loot’s location to a meek cellmate being released from jail. Big mistake. The bespectacled Jean-Louis (Stephane Debac) is considerably more dangerous than he seems. He swiftly nabs Franck’s wife, daughter, and hidden cash. This means our hero has to bust out of jail and—pursued by the police—hunt down Jean-Louis. So far, so good.

Dupontel, who’s got a widow’s peak to rival Justin Theroux’s, doesn’t look like your conventional action hero. He’s better at conveying the prior “Should I throw myself out the window to escape the cops?” calculation than the shattering glass and drop to the top of a conveniently parked van on the street. (Why is there always a soft-topped van parked beneath such windows?) And while you could accept Jason Statham, no great actor, jumping from 1) overpass to railway-station awning, 2) railway-station awning to moving train, and 3) train to the ground below, that kind of urban parkour stuff works against The Prey’s plausibility. And Dupontel is nothing if not plausible in his grind-it-out endurance: Franck gets beaten, shot, and bloodied, but still trudges forward—like Bruce Willis with hair.

Rather less plausible is Alice Taglioni as Claire, who looks fresh off the catwalk as the police detective pursuing Franck. Her hassles and colleagues at the station house are way too familiar from countless prior cop flicks (her “feminine intuition” is regularly questioned). Claire acquires a few bruises during the chase, but neither she nor any character gains any depth along the way. For all the running Franck does, he can’t escape movie conventions. When he reaches a cliff, you can be sure there will be a cliffhanger.

My last hope for The Prey fell to Debac’s nerdy villain, but even he lets us down. We’ve become accustomed to super-brainy and -malign serial killers at the movies, like Hannibal Lecter or Kevin Spacey’s ghoul in Seven. Jean-Louis is amusingly prim and priggish, wearing his fanny pack in front (!) and a sweater crossed neatly over his shoulders, yet we never get a sense of his core deviancy or competence. Franck is good at taking a beating; by contrast, Jean-Louis doesn’t seem very good at his job. Director Eric Valette does his job properly by pushing The Prey swiftly through its 102 minutes, all of them routine. Brian Miller

PStories We Tell

Opens Fri., June 7 at Seven Gables. Rated PG-13. 108 Minutes.

The phrase “spoiler alert” gains new currency in the realm of narrative documentary. The reveals and gotchas contained within them are probably already public record—but still, one hesitates to blow the incredible surprises of, say, Searching for Sugar Man for unsuspecting viewers. In the case of Sarah Polley’s Stories We Tell, we should be able to dance around the spoilers. And yet, because the actress/director wants not merely to tell a tale of her family’s life, but also to question the reliability of storytelling itself, we might wonder why old-fashioned issues such as suspense and surprise should be part of the program in the first place.

But Stories We Tell is suspenseful and surprising, even if the filmmaker might want to disown those qualities. Polley was a child star in her native Canada, won raves for her youthful roles in The Sweet Hereafter and Go, and snagged an Oscar nomination for writing Away From Her (2006), a much-liked film she also directed.

Stories We Tell begins as a portrait of Polley’s mother, Diane. A free-spirited actress who contrasted with Polley’s introspective father Michael (also an actor), Diane mostly sacrificed her career ambitions and had five children. She died when Sarah, the youngest, was 11 years old. We meet the filmmaker’s four siblings, father Michael (who wrote his own narration for the film), and a few of Diane’s friends. The movie begins to focus on Diane’s work in a play in Montreal, away from her Toronto family in a rare idyll, and the fact that Sarah was born nine months after this break.

Introducing the issue of parentage gives the movie a fascinating real-life subject. As though embarrassed by this fascination, Polley keeps shifting the focus to how we can find answers about a subject when everybody involved has his own perspective on the truth (even if her interviewees don’t actually contradict each other all that much). And she reminds us of the artifice of her movie: Even during her father’s sincere and painful voiceover, she is sitting at a sound board, occasionally prodding him to repeat a line for a clearer take.

This scrupulous approach is welcome in an era of sometimes navel-gazing “personal” documentaries. Indeed, the main element missing from Stories We Tell is an anguished confessional or teary breakdown from Sarah Polley. She prefers the role of questioner—interrogating both her subjects and the film form itself—which seems like an elaborate way of getting at (or avoiding?) the situation’s emotional core.

In that spirit, the late-arriving surprises involve not just new information about Diane’s history, but revelations about the movie we’ve been watching. As the storyteller in charge, Polley could’ve laid ou tthat stuff at the beginning; instead, she’s trained us to distrust the stories we tell, including, apparently, this one. Robert Horton

E

film@seattleweekly.com