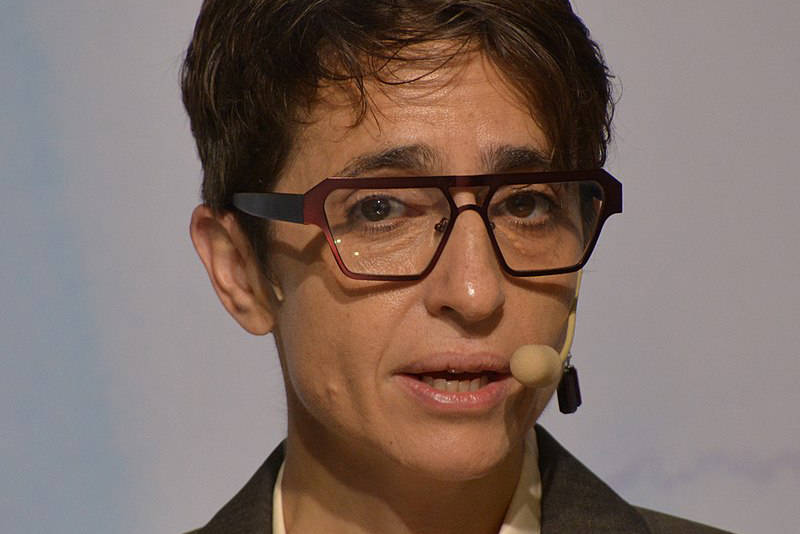

Okay, look: You’ve probably had a bad couple of years, and I don’t want to judge your emotional pain. But unless you’re one of the dozen or so music legends who died in 2016, the odds are good that Sherman Alexie has been having a worse time than you.

Alexie’s mother, Lillian, with whom he had a very complicated relationship, passed away in the summer of 2015. In the aftermath of Lillian’s funeral, something in Alexie’s heart cracked open and a flood of poems poured out. He would write multiple poems in a day, dozens in a week. They kept coming, eventually totaling in the triple digits. At first, Alexie considered publishing a book of poems about Lillian, but then it became a memoir with poems interspersed.

And then Alexie had brain surgery to remove a benign tumor that demanded immediate action. The tumor was removed successfully, but—because even minor brain surgery is still, well, brain surgery—Alexie couldn’t write at all for months. He could barely remember how to be a person.

And then, just when he was starting to go out in public again, just as he was finishing up a final draft of his memoir, America went and elected the self-described Second Coming of Andrew Jackson. For Alexie, who grew up on the Spokane Indian Reservation, Trump’s election probably felt like a personal refutation.

But Alexie recovered, because that’s what he does: He survives. And every time he survives, he seems to grow a little bit. If you’ve attended one of his readings lately, you might remember him as an even taller figure than in readings past—bigger, louder, wielding a devastating emotional payload. His personality is large and, as he survives each passing trial, it’s only getting larger; from his adoring audience’s vantage point, Alexie is now a giant.

The memoir that Alexie has been working on is finally out, and You Don’t Have to Say You Love Me is a suitably big book. It is thick and sprawling, and the cover is bright white, like bleached bone. Flip through it and you’ll find a blend of poetry and essays and short, paragraph-long bursts of observations. Read the book and you’ll see that it’s not a straightforward account of Lillian’s death or the linear story of Alexie’s brain surgery. Instead, Love staggers forward and back in time, reeling from an account of the bullying Alexie endured as a kid on the rez to the present-day barbs other Native writers throw his way for not being, in their opinion, Native enough.

Read the rest of this review in Seattle Weekly’s print edition, or online here at seattlereviewofbooks.com. Paul Constant is co-founder of The Seattle Review of Books. Read daily books coverage at seattlereviewofbooks.com