Interview Kinski’s Chris Martin and you’ll get an earful. Not, mind you, a lot about his own music, at least not without some probing. More likely about the records he’s been buying and his admiration for the groups his band has opened for, or even to tip the reporter to the cool but under-the-radar jazz improv scene that’s quietly brewing in Seattle.

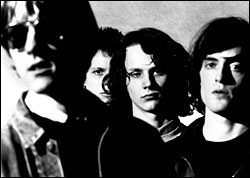

It isn’t that Martin’s not proud of his grouphe is. Since forming in 1998, Kinskiguitarist Martin, bassist Lucy Atkinson, guitarist Matthew Reid-Schwartz, and drummer Barrett Wilke (who replaced David Weeks last summer)have forged a sonic legacy that, to date, seems to have knocked critics’ proverbial dicks in the dirt. Yet even after I read back some glowing reviews of Kinski’s sets at the 2000 and 2002 Terrastock music festivals, Martin quickly shifts the focus, enthusing about seeing the likes of Bardo Pond, Major Stars, Acid Mothers Temple, and Six Organs of Admittance.

Humble? Maybe. But Martin, it turns out, got his fill of career angst years ago. Raised in Denver, he joined his first band while attending film school at Montana State University. After graduation, he landed in Seattle (picking it over another music town, Minneapolis), and by the mid-’90s was fronting his own pop combo, eventually releasing two albums.

“It was real heart-on-sleeve stuff,” Martin recalls, explaining why he’d prefer I not mention the band’s name. “It [now] sounds over the top to me. Not really ’emo,’ but very personaltoo personal! We really tried to make it, sending the records out to all the labels, just getting carried away. Then we broke up.”

DISILLUSIONED, MARTIN took a six-month vacation from even picking up the guitar. His epiphany arrived in the form of a record-shopping spree.

“All the Krautrock reissues, stuff like Ash Ra Tempel, Can, FaustI was blown away,” he says. “Also rediscovering Spacemen 3. I was basically just listening and not playing. When I did, I put material together from scratch in the bedroom, buying a pedal here and there.”

Ah yes. My notes, in fact, read, “Chris Martin: a man who never met an effects pedal he didn’t like.” And the sound of the early, three-piece Kinski (nee the Klauskinskis) was clearly descended from such noted gear fetishists as Sonic Youth, Spacemen 3, and My Bloody Valentine. After 1999’s self-released SpaceLaunch for Frenchie garnered positive ink, Kinski recruited Reid-Schwartz as second guitarist in time to help flesh out the sound of the follow-up, Be Gentle With the Warm Turtle, issued by Pacifico in 2001. By that time, the band already had U.S. tours with Hovercraft and Silkworm, as well as key appearances at CMJ and the Seattle-hosted Terrastock 4, under their belts. Slots at SXSW and Terrastock 5 would raise their profile even higher, and Martin now admits that Kinski have been remarkably fortunate in how quickly they have found an audience. Last year even saw the group go international: Kinski were invited to tour Japan with that country’s leading psychedelic avatar, the Acid Mothers Temple.

“The whole experience was amazing!” blurts Martin, clearly jazzed at the memory. “In Japan, all the clubs, at least the ones we played, are unbelievably tiny. There was this place in Osaka that could hold, literally, maybe 80 people, and they’d stuff in 140! But it was great, because in those clubs you were always playing to a packed room.”

Last year, Martin also released a solo ambient/improvisational album, This Is My Ampbuzz (Strange Attractors), under the nom de drone Ampbuzz, subsequently launching a similarly inclined side project with guitarists Atkinson and Reid-Schwartz that they christened Herzog. (Already taken, presumably, were “Fassbinder,” “Murnau,” and “Schlondorff.)

Meanwhile, there’s the new Kinski record, Airs Above Your Station, on Sub Pop, completed about 10 months ago with former drummer Weeks. It’s a steamroller of an album whose first 20 minutes alone are the most exhilarating I’ve heard in ages, in particular the Eno-meets-Melvins heavy atmospherics of “Steve’s Basement” and the tremolo-draped, into-you-like-a-train “Semaphore.”

Martin reckons the album achieves the group’s goal of marrying pop melodies to hard-rock dynamics, of bringing emotion to experimental music, and of meeting the “challenge of making songs without vocals interesting and not get repetitious or boring.”

“Challenge” indeed. Instrumental music tends to be the unmarketable, red-headed stepchild of the indie-rock scene.

“It’s funny because I was just thinking about that this week,” says Martin. “I was reading this Kraftwerk biography, and they were talking about the first few years when they were doing their ‘free’ stuff, the improv space stuff. They met some guy who recommended they get an image, wear the suits and ties, and have something that people could latch onto visually, have a theme. I was just scratching my head and wondering, ‘Should we think about that . . . ?'” he says, laughing. “It just seems so ridiculous to entertain it, yet now, every indie band is dressed up in black or something. I always hope that the music itself, as long as you put on a great showthat’ll carry it. As far as the marketing of an image for a mostly instrumental band, I don’t know where you’d start.”

Martin’s mention of the Kraftwerk bio prompts me to list a few of my favorite books on Krautrock and Japanese psych. He counters with some choice CD reissues he recently mail-ordered. And with that, we’re off once again onto a long and convolutedbut stimulating and revealingmusical tangent. Not unlike, dare I say it, the very tangents that the members of Kinski themselves are wont to explore.