WHO SAID THERE ARE no second acts in American lifeor at least none that are any good?

Reports of Steve Wynn & the Miracle 3 at this year’s South by Southwest conference found more than a few critics on bent knees before the quartet’s scorched-earth policy. No less than Seattle Weekly‘s music editor, Bob Mehr, reported that Wynn and co. performed two of the “loudest, hardest, and most passionate sets of music in Austin all week . . . with a power and volume that threatened to come gleefully unhinged.”

Compare that with yours truly’s notes of some 17 years’ vintage, describing how Wynn and his combo the Dream Syndicate systematically applied a wrecking ball to a North Carolina punk club one steamy summer night in 1986:

“The club owner is already freaked out from the volume at the sound check, so what does Wynn do during the set’s very first song? After vamping over a slow, jazzy intro and announcing to the crowd that the band’s been asked to keep it down (‘So don’t any of you talk loudly, break beer bottles, or flush the toilets,’ he warns), Wynn smirks evilly, stabs at his volume knob, and proceeds to careen full tilt into the power-chord funnel of ‘Until Lately.’ The club owner physically recoils from the sonic blast and is furious. The rest of us surge forward and are in ecstasy. . . . This is rock ‘n’ roll, and it doesn’t get any better. . . . “

“Yeah, we could do that a lot back then,” says Wynn today, laughing at the images I’ve just resurrected. “We were all about antagonizing! And the South by Southwest thingwe weren’t being very shy and diplomatic about it, either.”

Please allow me to introduce Steve Wynn, then, a man of musical wealth and taste.

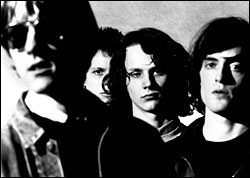

THE DREAM SYNDICATE: You at least know of the legendary L.A. outfit. Two of the four studio albums the band released during its 1982-89 tenure, 1982’s Days of Wine and Roses and its Sandy Pearlman- produced ’84 follow-up, Medicine Show, are nowadays deemed five-star classics. But raw stats and rating systems don’t tell the tale of this tape.

First of all, consider the alternate musical milieu in which the band operated, compared to 2003: no reliable club network, no Spin or Alternative Press message boards, no corporate-sponsored Vans Warped Tours to guide aspiring punkers through the mosh pit of life.

“I remember when we first started touring back in ’82, ’83,” recalls Wynn. “Outside of New York or L.A., the best you could hope for was to come to each city and play their ‘new-wave night.’ For all of us bands like the Dream Syndicate, R.E.M., Rain Parade, Sonic Youth, all the SST bands, Replacements, etc.there became a small circuit, a really kind of enthusiastic, new, naive, fan-driven, ‘commerce is secondary’ kind of circuit that was really exciting. Bands touring on ‘curiosity and enthusiasm.'”

Certainly, the word got out about the Dream Syndicate’s head-uncorking fusion of amphetamine punk and vertiginous psychedelia (keenly laced with, for good measure, Dylan/Lou Reed wordplay), and among fans who witnessed the group firsthand, there’s no question that the Velvet Underground Effect applied.

Wynn acknowledges the obvious, saying, “I think we did influence a lot of musicians, and I’m really proud of what we did. Maybe we didn’t sell a million records, but the level of enthusiasm, the love of the music per fan, per listener, per person who bought Days of Wine and Roses, was probably as high as any band you could imagine. I still meet people now, 20 years later, who say that record changed their life or they formed a band because of it. And that’s a great feeling.

“When we formed, we went out there playing whatever you’d call it’psychedelic garage’ or ‘indie/underground noise’and we weren’t seeing it anywhere. I think it just opened a lot of people’s ears to some alternative to Duran Duran or Haircut 100 or whatever people thought was hip and groovy at the time. We just say, ‘Nahh. There’s another darker, weirder, deeper, creepier side of underground music. Check this out!’ We were advocates for this music that excited us. And I think we had something to do with bridging the gap with what came beforethe Stooges, the Velvets, the Modern Lovers, Big Starand all the things that came afterwardsYo La Tengo, Nirvana, and bands like that.”

An ironic coda marks the Dream Syndicate’s story. Not long after the group disbanded in ’89, a northwest outfit called Nirvana commenced the trek toward the Year That Punk Broke. Wynn, who’d embarked on a solo career by that point, remembers feeling it was a sweet day of reckoning: “All this loud, distorted, feedback guitars is now the mainstream’Hallelujah! The time has come for the music I love and for my music as well!'” But he was wrong; the time had actually come for the gormless, characterless rumblings of the Candleboxes, the Bushes, the Lives, and the Matchbox Twenties. And while Wynn continued to make records throughout the ’90s, notching critical kudos for his solo records and his “indie supergroup” side project Gutterball, like many of his ’80s peers, he never got to cash in.

What he did instead was: tour, frequently in Europe, where his audience steadily grew; retain ownership of his master recordings (a strategy that would pay off years later when it came time to reissue his albums, most with bonus tracks); and in general set up a self- sufficiency module that would not only shield him against the music-biz vicissitudes of the new millennium but also yield an artistic triumph on par with his early classic Days of Wine and Roses.

BEFORE MAKING HIS eighth solo album in 2001 (not counting multiple import-only releases), Wynn, who’d lived and recorded in big cities his entire career, decided he needed to shake up his recording modus operandi. Taking a tip from friend Howe Gelb of Giant Sand and calculating that, in Tucson, Ariz., he could get twice as much studio time for what it would cost him in N.Y.C., he loaded up his band and flew West.

It was a fateful decision. Because when Wynn, drummer Linda Pitmon (ex- ZuZu’s Petals), bassist Dave DeCastro (Health & Happiness Show, Butch Hancock Band), and guitarist Chris Brokaw (Come, Pullman) returned home after 10 days in the desert clutching the master tapes to Here Come the Miracles, they sensed the title was prophetic.

“It was, hands-down, my favorite record I’ve ever made,” swears Wynn, citing the low-key vibe of Tucson in general and the efforts of Wavelab Studios chief Craig Schumacher in particular as keeping the experience both relaxed and focused. “The process, the resultseverything. It’s a good feeling when you finally walk out of the studio and say, ‘That’s exactly the record I want to hear right now.'”

It was also what the critics wanted to hear. The 19-song, double-disc Miracles was released in the late spring of ’01 on Wynn’s own Down There label and quickly generated the most glowing reviews of the man’s career, going on to top numerous year-end best-of lists. (No small feat here, either: Wynn says Miracles is the best selling record in his catalog, “better than anything [I’ve done] for a label in a gigantic midtown Manhattan building with a huge staff and tons of money.”) Miracles was, by turns, a showcase of garage-brawn, swamp-blues, and sun-drenched psychedelics but with a smart pop undercurrent that helped strike a deft stylistic balance.

Pundits also took due note of Wynn’s compelling narrative lyrical style, adding to the Dylan/Reed checklist of influences the likes of two-fisted authors George P. Pelecanos and Jim Thompson. Pelecanos himself famously noted, in an interview summit with the songwriter for Magnet magazine, that Wynn’s music is like “literature with guitar.”

Wynn recently took a literal, literary noirish turn in a new musicians-as-writers anthology, Carved in Rock; the Greg Kihn-edited book places Wynn’s short story, “Looked a Lot Like Che Guevara,” next to entries from Pete Townshend, Steve Earle, Ray Davies, and others.

“HARD-BOILED ROCKER Steve Wynn returns to the scene of the crime with his new album Static Transmission. . . . ” I’m reciting an imaginary pull quote for Wynn’s approval, and after thinking it over for a moment, he replies, “That

sounds goodbut I wonder if I was violating some kind of musical Mann Act by transporting my songs across state lines. Should have learned from Chuck Berry, eh?”

Return to the scene is exactly what Wynn did when it came time to make a follow-up to Miracles. Wynn and the band had pretty much toured nonstop after that album was released, and during a stretch in the fall of ’01, they were even seen performing the entirety of Days of Wine and Roses in honor of Rhino’s remastered/expanded edition of the seminal Dream Syndicate platter. So it was a thoroughly road-tested bandguitarist Jason Victor having replaced Brokaw, who couldn’t commit to Wynn’s stringent schedulethat flew to Tucson in late 2002, hoping to catch lightning in a bottle a second time.

Recalls Wynn, “I thought, why not? I liked the studio, liked Craig Schumacher, liked the way of working there. It was the first time for me where I said I wanted to do the same thing again. All the way back to Medicine Show, I would make a point to make the new record different from the one before, whether it was playing with different people or going to a different place or having a different style of songwriting.

“Of course, I should know betterit was two years later; a lot had happened in that we’d made a record we’d have to live up to, and it was a bit of a challenge, a little pressure. After a couple of days we said, ‘OK, we can’t make it the same way. It has to be a different record, a different experience.’ I can hear some of the similarities in sounds, in the players, and some of the styles. But they’re very different records at the same time.”

Indeed, Static Transmission, from the sequencing to the tenor of the songs themselves, is a moodier, more reflective effort. Given the huge shadow Miracles casts, Transmission has its critical work cut out for it. But close examination finds it on equal-but-different artistic footing with its older sibling, and Wynn’s just as proud, too.

As a New York resident since ’94, Wynn couldn’t help being affected by 9/11; for his Web site (www.stevewynn.net) he penned a moving essay about being at home in Manhattan that fateful morning. And while he opted not to write about the tragedy specifically, he freely admits that Transmission‘s tone “is influenced by the panic, fear, melancholy, uncertainty, defiance, mood swings, and emotional oblivion that followed.”

STATIC TRANSMISSION opens and closes (not counting a boozy, country-rock hidden track) on contemplative notes: the gospellish, calm-at-the-end-of-the-storm “What Comes After” and the peaceful, moving-toward-the-light “A Fond Farewell. The record bookended thusly, even upbeat tunes like the sunny, chiming “Ambassador of Soul” occasionally take on gray-shaded hues (it solemnly advises, “sometimes you’ve got to learn to walk away”). Elsewhere, a pair of character studies, the Bad Seeds-like junkie yarn “Keep it Clean” and the ’70s-funky, Kool-&-the-Gang-meets-Edgar-Winter-Group “Hollywood,” probe their protagonists’ efforts to steer clear of their own personal hearts of darkness. And speaking of defiance: The album’s centerpiece is a mighty rocker called “Amphetamine” that, sonically, suggests the Dream Syndicate rewriting the Stones’ “Sympathy for the Devil.” In it, a seventh-son-of-a-seventh-son mojo warrior hurtles down the midnight asphalt, vowing not to let his demons catch up with him. “But if I fear for the devil and I fear for myself, then I’m gonna have to fear for everybody else!” whoops Wynn in a voice that’s one part metaphysical triumph and several parts hopped-up recalcitrance.

“Temptation, facing whatever your Achilles’ heel isthese are issues I’ve come back to again and again,” admits Wynn. “I’ve got all the ugliness and meanness inside me like anybody else does. You keep certain things at bay, things you don’t like about yourself, by writing about it. But I’m not, ah, sitting in a bar all day with a whisky in one hand and a gun in the other!”

Emitting a low, satisfied chuckle, Wynn adds, “A friend of mind called the album ‘troubled-soul music.’ It suits the record. The whole thing is a ‘Lord, I’ve seen troubles and I’m gonna find my salvation’ kind of record. Looking from a period of darkness and trying to find your way out.”

Static Transmission was released in Europe in February, with Wynn & the Miracle 3 subsequently spending most of April and May overseas touring. With the album due stateside next month (like Miracles, it will be on Down There and distributed by Innerstate), Wynn’s determined to capitalize on his Miracles momentum and, in his words, “tour my ass off in America.”

And as mentioned earlier, American audiences got a preview of what to expect this past March at SXSW. Wynn characterizes the Austin experience with a statement that could also double as a career summary:

“It was all very defiant, you know? Making a point. Out there just totake no prisoners.”