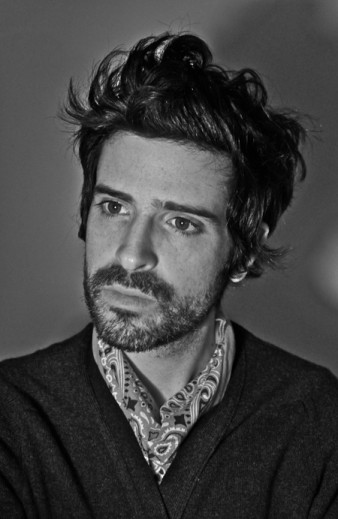

Even after more than a decade as a musician, folk artist Devendra Banhart is still trying to perfect the way he creates. For his latest album, Mala, Banhart recorded in a “shack” in Los Angeles with a small group of contributing musicians. While he enoyed what he calls an intimate process, recording in this manner taught Banhart that he still has a little tweaking to do. He talked with us about his parents, the intent behind Mala, and what he envisions for future releases before he plays Sasquatch! later today.

Your Sasquatch! performance is part of a longer tour you’re doing. How have those shows been? Really fun. We’re playing with a new drummer, an old friend, so that’s been a lovely adjustment. It feels like the first tour we’ve ever done, and it’s our “Discover America” tour.

What have you discovered about America so far? That my mom lives there [laughs]. She came to so many shows. It’s an awkward thing playing a show with your mom. It’s like going on a date and having your mom there.

Does she make it known that she’s your mother? She does. She goes to the bathroom and goes “What did you think of the show?” Then she surprises them, like, “I’m his mom!”

She sounds cool. She’s okay, but my dad actually inspired [Mala] because I think this album is music for all dads to come out of the closet to.

Did you intend that? That was the intent. Before we stepped into the studio, I thought “This is the mission statement. This is the manifesto.”

In “Won’t You Come Over,” you do sing about counting the flowers on your dress, so it’s appropriate. It doesn’t feel like a stretch. I feel like there’s a trajectory between all the albums and this one, even though this one is a transitional album, and I think it sounds it.

Seattle’s a place I often think about moving to. One of the cities I’d like to at least rent a place and write an album. There’s something very comforting about Seattle, and it’s so beautiful. There’s this almost humoring melancholy.

Hopefully you’ll get to spend some time here. We’re definitely going to cruise around and then head to the festival. A lot of friends have played it so to finally get to play it, it’s so exciting. Festivals are tough for us; we don’t really make festival music, but I think it’s going to be fine. A little tap dancing, duckwalk — pulling out all the stops. We’ll all play in coattails; it’ll be good.

Mala

sounds like a very casual, very natural record. How would you describe the writing and recording process? It was a very small group of people that are the main creators of the album, meaning me, Noah Georgeson, and Josiah Steinbrick … We recorded it in a small shack using a combination of atavistic technology and more contemporary technology. It was a very intimate affair.

There’s a distinction between insolated, isolated, and intimate, because you can have an isolated environment yet not take the responsibility to always make sure the final product is something you’re satisfied with. To make something isolated doesn’t necessarily mean it’s intimate. This was more of an intimate album.

When I say transitional, I think it’s transitional in terms of process. The process in the past was a more aleatoric one. It’s evolved, and I’d like to record in a proper studio, not build a studio. I would like to make music that is closer to having no attack, something more sensitive. I don’t think this record is exactly that, but it is a transition to something closer to that.