Dance by Sandra Kurtz

Olivier Wevers has been developing into a skilled and thoughtful choreographer with his company Whim W’him. But when he works with material that comes from his ballet background, he stretches just a bit further. In January at Cornish Playhouse, his witty take on Les Sylphides translated the moonlight and poetry of the Fokine original into a hipster dinner party. It was as smart as it was silly.

Performed in February at Bellevue’s Meydenbauer Center, Chop Shop has become an annual valentine to contemporary dance, rounding up a generous program of local and national artists. Director Eva Stone has upped the ante every year, and this edition was packed with kinetic energy. Carl Orff’s cantata Carmina Burana is a staple of the choral repertory, and has been fertile material for several choreographers, who usually go with its bawdy medieval text. Spectrum Dance Theater’s Donald Byrd, who loves to switch things around, took a different pathway and in March staged this workshop Carmina as a revival meeting. (He’s supposed to come out with a full version in 2015.)

Lewis Carroll wrote stories that were as much for adults as they were for children, and burlesque artist Lily Verlaine took full advantage of every opportunity in April’s zestful Burlesque Alice in Wonderland, seen at the Triple Door.

Seattle Dance Project was created to give mature dancers a place to explore new options. Yet after almost six years of thoughtful work, the artists involved have come to another bend in the road and folded up the ensemble. They left us with a lovely final program in May at Broadway Performance Hall, including Want, a new work by Wade Madsen that featured each performer, combining their kinetic skills with their human resonance.

Pacific Northwest Ballet continues to burnish its loving restoration of the Romantic-era classic Giselle. In 2011, PNB staged a version that brought back all the nuances from the original choreography. This May, it commissioned new sets and costumes to match that period feel. A beautiful production looked even better.

There are over 17,000 islands in the Indonesian archipelago, and there is at least one distinct dance for each of them. With July’s performance by Malam Budaya at Langston Hughes Performing Arts Institute, we saw a handful of those works, up close and in exquisite detail, with a small ensemble led by Astrid Vinje.

There are as many kinds of virtuosity as there are performers in the Men in Dance festival (which returned to Broadway Performance Hall in September). Highlights this year included Aaron Loux in a revival of Mark Morris’ folk-inflected I Love You Dearly and sometime Seattleite Bill Evans, in a beautiful tap solo, organizing multiple rhythms with his feet.

Choreographer Amy O’Neal deserves all the attention she got for Opposing Forces, along with her phenomenal performers (Alfredo “Free” Vergara Jr., Brysen “JustBe” Angeles, Fever One, Mozeslateef, Michael O’Neal Jr., and WD4D) for this program that both draws from and extends hip-hop dancing. (October, On the Boards.)

Visual Arts

By Brian Miller and Kelton Sears

SAM’s summer exhibit Modernism in the Pacific Northwest: The Mythic and the Mystical leaned most heavily on Mark Tobey, Morris Graves, Kenneth Callahan, and Guy Anderson, though the survey extended to their artistic heirs. For me, the real revelation—among some important new gifts from Marshall and Helen Hatch—was a few Seattle street scenes from Tobey, made before his “white writing” breakthrough. They have the same pulsing, teeming energy—a kind of Whitmanesque I-among-the-many quality. They’re both ashcan-prosaic on the one hand and deeply spiritual on the other. BRM

Seen at G. Gibson Gallery early this spring, Cable Griffith’s paintings in Quest push past the “Are video games art?” debate and the schlocky glut of fan art flooding the city by taking game-inspired environments and turning them into brilliant, massive landscapes of their own. Makes sense for an artist who cites the Elder Scrolls series and The Legend of Zelda as some of his main inspirations. KS

Though I didn’t have time to write about the photos of Daniel Joseph Martinez at James Harris Gallery this fall, they really stuck with me. To the desolate, empty storefronts of his South L.A. neighborhood, Martinez adds political text (“Thank You, Mr. Bush”). Then there were the hunchback portraits: The artist using prosthetics and makeup, head covered with masks or adorned with a bishop’s hat, prayers from different creeds inked on his naked, contorted torso. Faith becomes ugly and twisted. In Reflections From a Damaged Life, there’s a sense of wreckage both spiritual and physical. BRM

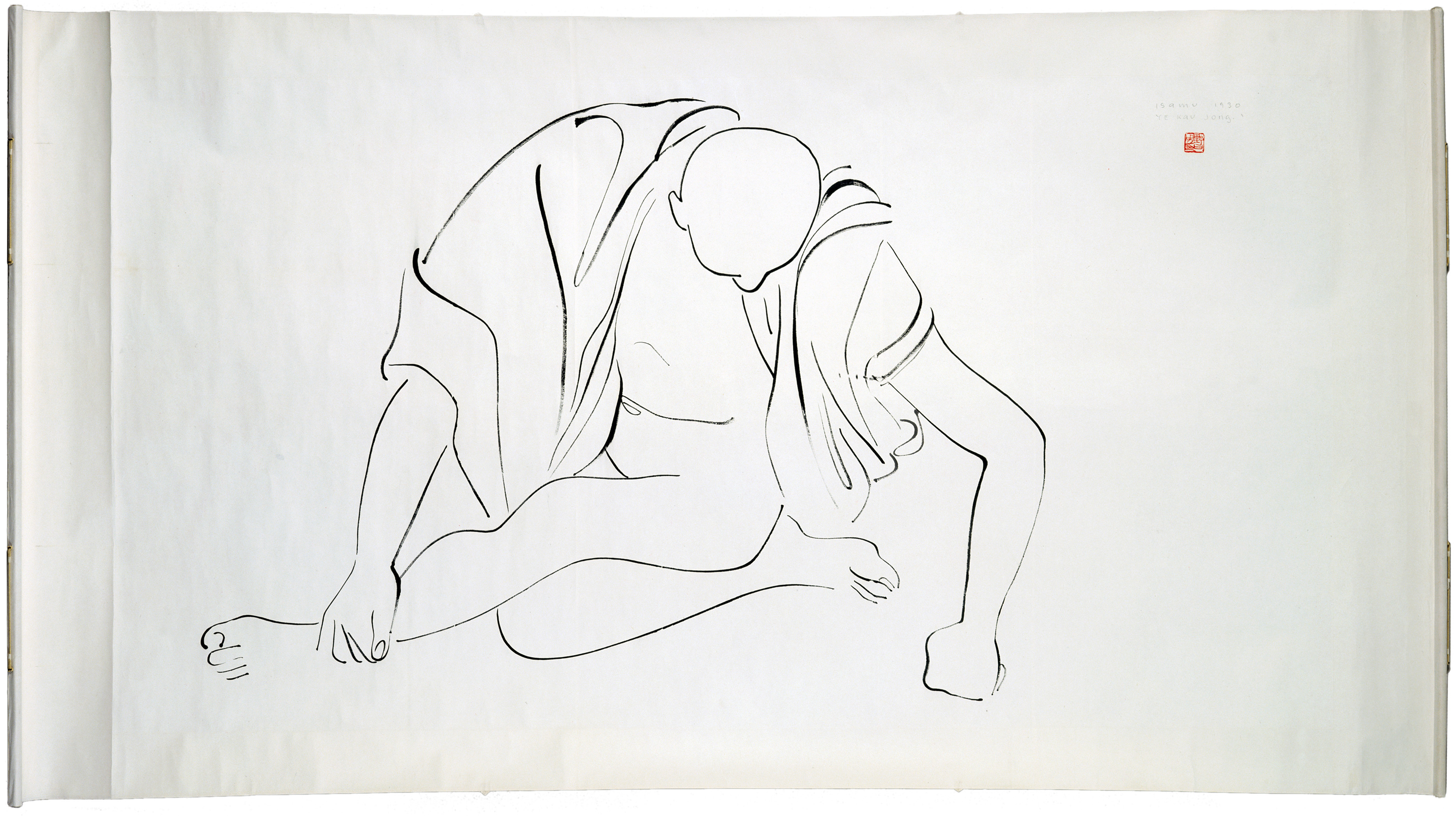

The Frye presented two spring shows with a transpacific theme: Isamu Noguchi and Qi Baishi: Beijing 1930 and Mark Tobey and Teng Baiye: Seattle/Shanghai. Together they offered a terrific educational primer on the currents of Asian art that washed onto these shores with such force in the prewar years. For sheer visual pleasure, however, it’s hard to top the large series of calligraphy-brush paintings by Isamu Noguchi, a anomaly in his long career a sculptor. Just simple black-on-white figure studies, really, they reduce the human form—compassionately and playfully—in a thoroughly modern direction. BRM

A Japanese artist based in Hawaii, Yumiko Glover showed sad yet bright colored paintings in Moe: Elements of the Floating World at Bryan Ohno Gallery this fall. Her almost gaudy acrylic paintings look back uneasily on a native culture saturated with anime imagery, sex, video games, schoolgirl fetishes, naive folklore, and the whole kawaii industry. Moe is a slang shorthand for idealized youth and femininity, where the creepy meets the innocent—usually from a male perspective. Glover’s girls push back against the orb-eyed pixies and too-short plaid skirts so common in manga. BRM

Suyama Space is a great gallery because it allows artists a sense of scale that’s not available elsewhere. Lillienthal|Zamora’s enormous fall installation Never Finished, with its spider webs of dangling power cords and cascading fluorescent light tubes, filled the space not just with its physicality, but its light. KS

Local artist Dan Webb is known mainly as a carver of wood, and much of that material was on view in Fragile Fortress at BAM this spring. How he hews a dandelion, say, from a solid block of old timber is fairly amazing. But I loved an earlier work made from his days not long out of Cornish: a medieval suit of armor, like something you’d expect to see at the Met in New York, only it’s constructed out of silvery duct tape. It wouldn’t stop a lance or an arrow, and the piece—as other Webb creations often do—somewhat humorously alludes to its own humble material. BRM

Prior to his June show at Gallery4Culture (Our Alley), Scott Kolbo recruited his kids and their pals to stage playful scenes in a lawless, enchanted alley inspired by his own Spokane childhood. He videotaped those scenes, added effects, then traced over them by hand, creating a busy lattice of pencil outlines and gestures. In glowing light boxes, those overlaid drawings and the videotaped source characters gradually converged or settled into new compositions within the same frame. Childhood was put on pause, repeatedly, revealing new facets of play. BRM

SAAM’s summer show Deco Japan—entirely sourced from Florida collectors Robert and Mary Levenson—was an odd melange of stuff: posters, kimonos, postcards, ashtrays, furniture, vases, etc. At the same time, it was fascinatingly specific, covering the years 1920-45, when Japan was rapidly industrializing and opening itself to the West. This was a time of luxury, speed, and streamlining for the urban elite; and most of the items in Deco Japan felt like artifacts, not art. Yet I loved the glimpses into an ephemeral, hedonistic demimonde. The sheet-music covers and matchboxes reveal bare legs, high heels, neon glimmers, bobbed hair, martini glasses, and cigarettes—once forbidden frivolity soon to be snuffed out war and the atomic bomb. BRM

Maikoiyo Alley-Barnes, Nicholas Galanin, and Nep Sidhu’s effortlessly cool, transcendental work managed to confront racism and colonialism while somehow maintaining a sense of humor. Represented in the Frye’s summer exhibit Your Feast Has Ended, these artists are making new myths for the modern age. One of the most thought-provoking shows of the year. KS

Seattle photographer Matika Wilbur earned a solo show, her first, at TAM this summer. In it she presented about 50 portraits from her Project 562, which seeks to portray members from each federally recognized tribe in the U.S. Wilbur’s portraits reflect the preferred self-image of her subjects: If they want to wear traditional costumes, fine; if they favor golf shirts and baseball caps, that’s also fine. Wilbur aims to capture each individual at their dignified best, but her images aren’t the romantic depictions of an outsider (like Edward S. Curtis). They also served as a welcome prelude, if not rebuttal, to TAM’s new Haub Family Collection of art from the Old West. BRM

Running through January 11at SAM, Pop Departures features the expected big names—Warhol, Lichtenstein, Oldenburg, and company, who so thoroughly disrupted the art scene of the 1960s. The first part of the show (i.e. the big names) is better than the back nine, as we pass through the ’80s to the present day. There’s also not enough of any one artist, a problem inherent to any group history show. Case in point: The word paintings of Ed Ruscha; I could look at them all day. There’s irony and humor to his work (as in America Her Best Product), but also the bygone appeal of crisply executed ads and slogans that no longer sell to us. BRM

Stage

by Margaret Friedman, Brian Miller, and Kevin Phinney

In Arthur Miller’s The Price, staged by ACT in June, Charles Leggett plays a demoralized cop revisiting his parents’ apartment to sell the furniture. Alone, he turns on the Victrola and laughter erupts from the 1930s vinyl (or whatever records were made from back then). We watch his character catch the ha-ha’s, a divine affliction so endearing it almost vindicates the online-dating cliche “loves to laugh.” MF

Little Shop of Horrors is where Alan Menken—the tunesmith behind so many animated Disney classics—first found acclaim by pairing jukebox jingles with Space Age sci-fi. In March, this 5th Avenue/ACT co-production hit all the high notes, adding a few flourishes that even the original Off-Broadway show missed. Fun for the whole family, if you excuse the carnivorous plant at center stage. KP

The night before his death, as envisioned in The Price, MLK (Reginald Andre Jackson) spends a flirtatious, slightly putrid, and very human evening with angelic chamber maid Camae (Brianne A. Hill), who ultimately leads him through a dazzling multimedia retrospective of civil rights struggles, fortitude, abuses, and beauty. The Gotterdammerung orchestrated this September in ArtsWest’s intimate theater came at the viewer from all directions, with screens on every wall—a maelstrom of meaning en route to tragedy. MF

June’s production of The Hunchback of Seville by Washington Ensemble Theatre may have been too shrill for its own good, but don’t say you weren’t warned: Chambermaid Espanta (Rose Cano) appeared every few minutes to provide some new dire prediction, while carefully riding the edge between comic understatement and scene-stealing. Brilliant. KP

During Book-It’s June production of The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay, amid dozens of uber-cool cartoon-inspired visuals, the ice storm—simulated with strobe lights and a rickety plane in an arctic landscape—remains seared in memory. Kavalier flies on a vigilante revenge mission for which the raging, blinding blizzard constitutes a near-perfect metaphor. MF

No matter whether he’s playing Ebenezer Scrooge, Sherlock Holmes, or the emasculated husband in Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? at Seattle Rep last April, R. Hamilton Wright is Seattle’s jack-of-all-trades. He’s terrific in a lead role, knows when and how to pick his moments as a supporting cast member, and directs with a rapier-like clarity. Miss nothing he ever does, and you’re sure to believe Seattle is a world-class theater town. KP

All the Way/The Great Society (ending Sunday at the Rep). So many moments that hit you in the chest: LBJ swiping Dixiecrat Senator Dick Russell’s gravy at table; the ghost of a cop-murdered black man infusing MLK with resolve; LBJ, ensconced in the burned rubble encroaching upon his White House living room, agonizing over the Vietnam War condolence letters he must write. MF

Jack Willis, playing a titanic LBJ in The Great Society (and All the Way), gets a huge laugh about Medicaid, of all things. How could anyone be against expanding Medicaid, so popular when President Johnson introduced the program in 1965? Yet today Seattle theatergoers have seen how Republican governors of Southern states oppose Medicaid expansion because it would help … those people. Yesterday’s dull social program becomes today’s punch line. That’s political progress, I guess. (Also: in All the Way, the exhuming of a slain civil-rights activist’s corpse from a center-stage grave while the play’s action continues around it.) BRM

Although this fall’s Seattle Shakespeare Co. production of Twelfth Night didn’t produce much mirth, it did yield some surreal images that illuminated truths about the inner psyche of the play. To wit, when heroine Viola rifles through a shipwrecked treasure chest and finds a man in tuxedo within it, presaging her own walk on the male side. And later, cross-dressed as a man, she hallucinates her male twin (Sebastian) in female drag. Uncanny! MF

I wasn’t crazy about the spring revival of King Lear (also by Seattle Shakes). I disliked Lear’s wheeling Cordelia’s dead body out to us on a trolley cart. Yet now I must admit that that particular image has lodged permanently in my mind. Less sentimental than his carrying her in his arms, it may be a more plausible, character-revealing (if chaste and mercantile) directorial choice on Sheila Daniels’ part than I gave credit for. MF

Classical by Gavin Borchert

Six Grammy nominations; a Pulitzer prize for a piece (John Luther Adams’ Become Ocean) it commissioned and premiered; a Carnegie Hall concert (built around Adams’ piece) that was the toast of NYC’s Spring for Music festival, preceded by a no-less-fascinating chamber concert at hipster epicenter Le Poisson Rouge; and a viral video with Sir Mix-A-Lot that outraged everyone in the classical-pundit world who deserved to be outraged—the Seattle Symphony could hardly have had a more triumphant year.

The tinderbox of identity politics brought picketers and nationwide media coverage to—Gilbert and Sullivan? (Perhaps not so incongruous when you remember that Gilbert satirized Victorian England in practically every lyric he wrote; up-to-the-minute controversy is in the operettas’ DNA.) The Seattle G&S Society’s July production of The Mikado led to an air-clearing (and, thankfully, not-too-show-trially) roundtable at Seattle Rep on the intersection of race and theater. Though the Society does traditionalist productions of G&S nearly as well as they can be done, if this leads them to think a bit further outside the box from now on (and if they watch the eye makeup next time), the result of the clash will have been positive all the way around.

At Cornish College, British pianist Jonathan Powell devoted eight hours (with two intermissions) to the 1949 Sequentia cyclica super Dies irae by Kaikhosru Shapurji Sorabji (1892–1988), an Amazon-jungle profusion of contrapuntal and harmonic complexity on top of its epic length. About 50 listeners showed up for part one, 20 for part two; but the six of us who remained for part three will likely never forget it. And in two concerto performances, pianist Mark Salman reminded me of the special thrill of orchestral performances in intimate spaces: a thunderous Liszt Totentanz with Orchestra Seattle; and a rousing, dance-in-your-seat reading of Shostakovich’s manic Concerto no. 1 with trumpeter Brian Chin and the North Corner Chamber Orchestra.

Only one thing distracted me during November’s enrapturing first concert (Handel, Britten, Shostakovich, and a very tasty premiere by Roupen Shakarian) by the conductorless North Corner Chamber Orchestra: I couldn’t stop thinking of all the repertory I can’t wait to hear them do in the future.

Though Seattle Opera had an otherwise notable year—welcoming its new general director Aidan Lang and the return of the International Wagner Competition—the music theater that’s really stuck with me happened elsewhere: an audaciously gasp-inducing Jerry Springer: the Opera at the Moore and a sparkling and heartfelt A Little Night Music at SecondStory Theater. (Stuck with me, I mean, in a positive sense: I have no trouble recalling what I felt as I walked out of SO’s performance of Menotti’s enragingly exploitative and fraudulent The Consul in March.)