When we refer to someone as “classically trained,” what we essentially mean is that they’ve learned notation and nomenclature: how to read music and put it down on paper. But notation is not a skill that pop music necessarily requires, which creates a sort of elitist divide between the two performance traditions—and there’s often a consequent whiff of how-dare-they condescension whenever one of them approaches our lofty realm.

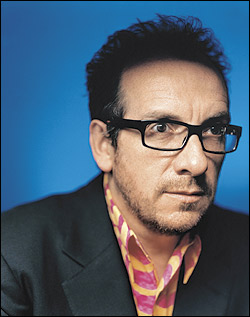

Elvis Costello, for example, decided to learn notation in the early 1990s when he became an admirer of the Brodsky String Quartet and wanted to work with them. The result was his mordant and luscious Juliet Letters, a song cycle written in 1992 for himself as vocalist with the quartet. The arranging process, in which all five participated, became the perfect laboratory for Costello to learn how to convey his ideas though the subtle and often frustrating medium of ink on paper.

Now he’s come out with a more ambitious, if less successful, work: Il Sogno, a full-scale, hour-long orchestral score for an Italian dance troupe’s adaptation of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, given a high-profile launch on prestige label Deutsche Grammophon with the San Francisco Symphony’s Michael Tilson Thomas conducting. As befits Il Sogno‘s origins as an accompaniment to visuals, it’s pretty cinematic. Hearing it, you might think of John Williams, though it’s less sugary; you might oftener think of Danny Elfman, though Costello’s harmonic palette is subtler and ranges wider. The orchestration is vivid, the ideas snappy, and . . . and you wait and wait for something to really stick in your ear. Still, as a whole, Il Sogno is at least as listenable and engaging as many of the new orchestral works I come across.

Paul McCartney has gotten away with (whoops! There’s my bias showing) not learning notation his entire life and yet managed to eke out a notable career. For his recent “classical” pieces, he’s worked with professional orchestrators and MIDI software to translate his piano ideas into orchestral terms. His Liverpool Oratorio (1991), for orchestra, chorus, and two soloists, presents the life story of a Merseyside Everyman whose biography has a lot in common with its creator’s (leaving out the part about becoming a billionaire)—sort of a there-but-for-meeting-John-Lennon-at-Woolton-Fete-go-I tale. It’s charming and moving, and it leaves you with tunes to hum. Standing Stone (1997) is a CD-length orchestral tone poem based on his own fanciful, invented quasi-Celtic saga. Working Classical is the title for his recent collection of three orchestral pieces and several pretty bonbons for string quartet, some inspired by Linda McCartney’s death. Here’s where both McCartney’s and Costello’s experience as three-minute songwriters betrays them. Their longer pieces wander terribly while the short ones hang together. This is only to say that they’re at their best as miniaturists, like Chopin, Schumann, and Grieg—or Bach, for that matter, who very rarely ever composed individual movements longer than six or seven minutes.

Speaking of Chopin: You’ll enjoy Billy Joel’s Fantasies & Delusions, his 2001 disc of solo piano works, to the extent you can get past its extreme derivativeness. It’s primarily Chopin with a slight Parisian savor, as if you’d asked a B-list French composer, say Edouard Lalo, to do his best Chopin imitation. They’re pretty, well-crafted, and go down easily. His “Film Noir” Fantasy goes further: A pastiche of a pastiche, it’s a throwback to the Rachmaninoff rip-offs so popular in British movie melodramas of the ’40s and ’50s, the “Warsaw Concerto” and the like.

If all these pieces are on the fluffy side, and not as strong as the best of their composer’s pop songs, neither are they too pretentious. Well, Joel’s longer pieces do have their pompous moments—if it helps to hear his sweeping Liberace gestures as camp, be my guest. But Costello and McCartney, to their credit, didn’t get self-serious as they approached the august portals of (cough, cough) Classical Music. They treated the string quartet and the orchestra as new sonic worlds to explore with a healthy sense of curiosity and sportiveness, rather than as something to be lived up to, residing on some exalted plane above guitars and drums. Even the vast, mythic Standing Stone has a picturesque storybook quality about it that keeps it likable. A slight carefulness, at worst, taints these pieces—but you hear that in the work of any orchestral newbie.

Costello takes just the right attitude when he writes in Il Sogno‘s liner notes: “My orchestrations may not obey certain conventions, but they sound just as I imagined them. I have learned by listening. I’m just using common sense and writing down what I want to hear.” Basically, that’s all “classical” composition is. If the term means anything, it means that one person is responsible for every note—they’re yours and no one else’s.