It is 2015 and people still don’t give electronic music the time of day. Decades after its birth, having taken over the radio (even Brittany Spears had a dubstep song in 2013, and Taylor Swift cribbed club-ready bass synths the year before), people deny that electronic dance music is a legitimate form—Time Magazine going as far to run an article with the headline “Dubstep—the Music Trend That Just Won’t Go Away.”

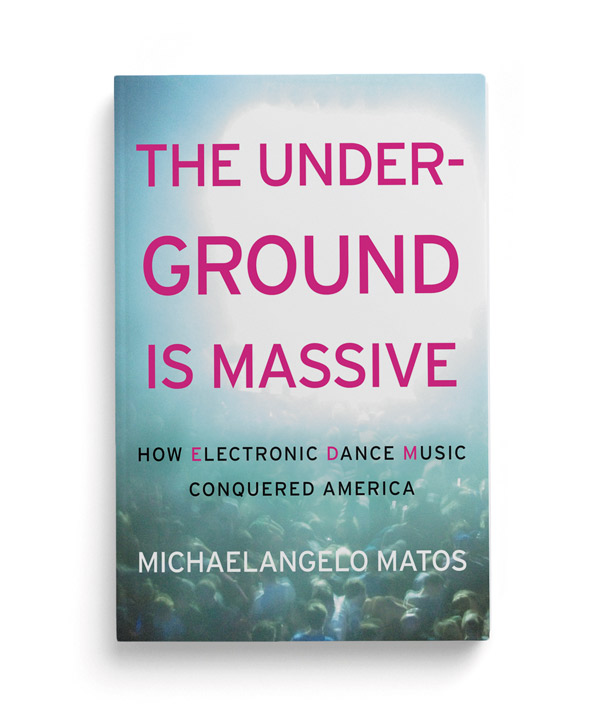

But to legions and legions of people, electronic dance music is a very real entity—it’s a way of life. But because of its underground nature and the open derision it’s had to endure since its inception, the music’s full story hasn’t really been told. Former Seattle Weekly music editor Michaelangelo Matos’ new book, The Underground is Massive: How Electronic Music Conquered America attempts to fill this void—presenting the fullest picture of electronic dance music yet. Stretching all the way back to Larry Levan’s Paradise Garage and the origins of house music, and ending in present day with the advent of brostep, the remarkable boom in the music festival industry, and the cultural takeover of Daft Punk, Matos walks the reader through the untold history of a maligned but undeniably influential form with incredible detail. In anticipation of Matos’ book talk tonight at Elliott Bay Book Company at 7:00 p.m., we sat down to chat raves, Skrillex, and rockist B.S.

How’d you get into dance music?I liked dance music pretty much from the beginning of my knowing about it. I was a voracious reader of the press by ’89, and by ’90, I’m 15, and I have some idea of what house music is. I don’t know the ins and outs of it, don’t know much about DJ culture, but I like the stuff on the radio. Black Box and Technotronic, stuff like Deee-Lite. I really liked “Good Beat.” There was a lot of pop/dance crossover in that era. I remember reading about raves in magazines and having a jumbled idea of what they were.

There was this big concerted effort to sell the “Madchester” scene at that time, Stone Roses and bands like that. A lot of Americans thought these guitar bands from England who had been turned on to acid house were “rave.” I talked to one guy for the book who said “I never understood why I went to all these parties and there was just dance music.” He had no idea why this music he was seeing at these things didn’t have guitars—these wires had been crossed. Americans thought of everything in terms of guitar bands. Around ’91 is when you started to see compilations of techno appear, and that’s when I started paying attention to that side of it. By ’92, when the labels in America start to try and push this, that’s when it explodes in the States, reaches the Midwest in concentrated fashion, and raves start to happen where I was in Minneapolis.

When was your first rave?I went to my first rave in the spring of ’93 when I was 18. It was at this place called the “Heart of the Beast Puppet Theatre.” They didn’t quite know how to make it a rave yet. I think my second or third party I went to was my first real rave—you know, fucking cavernous warehouse, really dark, a bunch of projections on the wall, and no pop music playing.Were there inflatable bounce houses like you write about in the book?Nah, none of that shit happened in the Midwest at that time. That was all in L.A. where that stuff happened, and stayed happening. It never stopped happening that way in L.A. even though it stopped happening everywhere else. They patented the whole bouncy house, carnival thing. After ’93 you didn’t see that in many other places.But they still have those all over festivals like Tomorrowland in Belgium don’t they? It’s like Disneyworld from the pictures I’ve seen.I went last year! Sort of, yeah. Tomorrow World is much the same in Atlanta. But what I’m saying is, that paradigm didn’t exist for a long time. From the mid-90s to the mid 2000s you didn’t see that. Maybe you saw it in Belgium, but I’m talking about in the U.S.

What was it about dance music that grabbed you versus rock?

I still love rock, I’m a rock critic, but I think it’s interesting that dance music… it stymies people who aren’t a part of that world. Recently, someone tried to argue with me that dance music subgenres existed only as a smokescreen to keep outsiders out and didn’t actually have to do with how the music sounded. In fact, dance subgenres exist to tell you precisely what they sound like. This bonehead wouldn’t fucking let up. I was like “well, you’re stupid.” That’s one of the interesting tensions in the book, this tension that stretches all the way back through dance music’s history. People denying that it’s really music.Or that it even exists! I’m saying that as somebody who has thought that way at times. In 2011 when I started hearing dance music was back and was going to explode in America I sort of scoffed because I’d been through that before. It was supposed to happen in ’92 and didn’t, then in ’97 and didn’t, and then it got outlawed in 2003 [via the R.A.V.E. act, sponsored by then Senator Joe Biden]. I also saw that tension through the other end as a writer trying to pitch pieces. I went to Ultra in 2013 and I saw Disclosure play in a small bowl with maybe 300-400 people. By the end of the set, they filled the whole bowl with maybe 2000 people. It was in the middle of the day and they weren’t headliners. I told an editor, “look I just saw these guys and I’m telling you they’re going to blow up.” Their album was about to come out in three or four months. And he said “I don’t think our readers are ready to go down that rabbit hole.” Then they became #1 in every country and now they’ve worked with Mary J. Blige and basically fostered last year’s Grammy sweeper [Sam Smith]. You can’t tell people who don’t want to talk about dance music about dance music. They don’t want to hear it. To whatever degree the book is a counteraction to that, and it is, there is always going to be someone whose entire attitude is “this isn’t real!”Why do you think there is that resistance?

It has to do with a lot of resentment—“disco sucks” holdover. People are allowed to have their tastes. But its a very different apparatus. You aren’t judging it on the same criteria you judge a rock song on. The beats are automated. People are offended by the tonalities of dance music who were raised on rock. Even people raised on hip hop, which is funny—the joke is, pop and hip hop music have been cribbing from dance music for so long, there’s nothing left to resist. You really have to be a rockist stick in the mud to not at least allow that dance music means things to people. In the book you write about how when Daft Punk revealed their giant mothership pyramid in 2007 it was the moment dance finally crossed over to a lot of people who hadn’t “got it” before. I’d never really thought of that as “the moment” before, but I remember how excited people were when that debuted.

That was it. It was game over. That was the beginning of the end.

Everyone had that “holy shit” reaction except for a few people, one of whom was a rock critic who wrote a review of it and was just like “oh I’m tired I’m going to bed.” It’s like, congratulations, you just swept aside the most important performance of your generation.

It was the Beatles on Ed Sullivan. That’s exactly what it was. Literally, overnight, everybody’s mind changed. They went “oh, I see how it works, that’s what everybody’s been responding to all these years. The riffs are great. The 303 is awesome. Acid lines are fucking cool.” They aren’t responding to anything that different than was going on in a typical DJ set that originally inspired those guys in Daft Punk. It’s not song based. That trips people up initially. People like songs. But I like music. Music doesn’t have to be sung or three minutes long. People think the structurelessness of a DJ set is bad, but it’s not, it’s a feature of the music. Now, every festival is festooned with dance music. Even the earliest Coachella was two-thirds electronic music. Okay, speaking of Coachella, let’s talk about Brostep, which you write about a lot towards the end of the book.Yeah I mapped out its trajectory in the book—It’s fascinating because dubstep was like, the #3 top selling genre in 2007, and its #6 or #7 now. It’s fallen off a cliff. It fell hard. Skrillex is the best and worst thing to happen to it—he culminated and codified what “brostep” became, and it became really boring after that because everyone jumped on the ship and did the same exact thing. And don’t get me wrong, I love some of that shit, Skrillex’s Essential Mix from two or three years ago is fucking great. “Bangarang” is one of the best singles of the decade, its a fantastic record. I don’t like everything, I don’t like his fucking Doors thing. Brostep… house just kind of came back in a hurry. The aggro side of things went more to 4/4 tracks, like “Turn Down for What.” Those songs became the move. It was a way of getting that aggro thing out with the 4/4, instead of the bass drops, which became such a caricature. Everyone had a bass drop in their song, every pop star had a dubstep song. It just oversaturated the market.

It definitely seems like it became a parody of itself.A lot of younger kids outgrew it, EDM. EDM means a very specific thing, this thing that happened this past decade. “Electronica” points to a specific era too—it means the 90s. EDM is like “new wave” in that it points to a very specific period. But EDM is not a genre, it’s a format. When I say EDM, when you go to the festival and you hear it, it’s EDM. It’s funny, there was this great article in Billboard recently about how to the panel that picks who gets in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, these new wave bands like The Cure and Depeche Mode will always just be these little niche bands from this one period, but those bands have been headlining festivals for like 30 years now. They’ve been huge for decades and influenced countless bands, but you’re never going to get that past people who think David Crosby is still relevant. It’s the same with dance music. I heard this great quote recently, “for techno, rock didn’t even exist.” I think that’s totally true. Because rock critics have this rock only lens, there’s literally this whole musical world that doesn’t have any literature on it. That’s what I was trying to fix with this book.ksears@seattleweekly.com